- ← Choke Points: Our energy access points

- Domestic sources integral to U.S. energy security, but may be vulnerable →

The diplomatic defense of energy

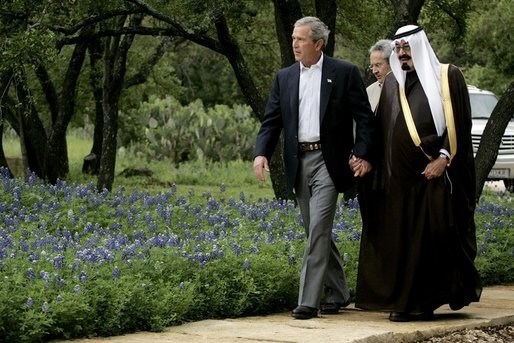

The image of President George W. Bush walking hand-in-hand with Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Abdullah during a 2005 meeting at Bush’s Crawford Ranch in Texas is emblematic of the power of oil to create alliances among otherwise unlikely partners.

Throughout history, the U.S. government has built close relationships with oil-rich countries like Saudi Arabia, Ecuador, Algeria, Equatorial Guinea and Azerbaijan. In the process, Washington often has overlooked significant policy differences, patterns of corruption and human rights abuses and anti-democratic actions of these governments.

According to many critics, it has done so to ensure U.S access to their vast oil reserves.

Below, we take a look at some of these complex, tangled relationships that the U.S. has fostered around energy issues.

We spent a week in Ecuador to report on the relationship between the smallest member of OPEC and Washington and to explore what big changes in Ecuador’s oil sector– and throughout Latin America– might mean for the future of U.S. energy security.

Ecuador

QUITO, Ecuador — With spears pointed at police, tribesmen from Ecuador’s indigenous groups loudly protested outside a hotel here recently, decrying the government’s latest effort to lease their ancestral lands in the Amazon basin to foreign oil companies for exploration and drilling.

Ecuador, the smallest OPEC country, produces 500,000 barrels of oil a day, with some of that exported to the West Coast of the United States. But in recent years, production has stagnated, in part because President Rafael Correa’s anti-American rhetoric has scared off American oil companies that have the technology and financial resources needed to get the oil out of the ground.

As his relationship with the United States and its multinational oil companies has soured in recent years, Correa has increasingly looked to China to take its place and has found an extremely enthusiastic partner. Since 2009, China has provided Ecuador with billions of dollars in loans and financing for infrastructure improvement, such as the 2010 agreement to build the $1.7 billion Coca Codo Sinclair hydroelectric dam to power 75 percent of Ecuador’s energy needs starting in 2015. In exchange, Beijing has secured access to Ecuador’s potentially significant oil supplies, which it needs to fuel its rapid economic growth.

Ecuador expects as much as $1.2 billion in foreign investment in the latest licensing round that caused the protest by indigenous groups. State-owned oil companies in Peru and Colombia have expressed interest in the oil blocks. And the China National Petroleum Corporation’s branch in Ecuador, Andes Petroleum, also has shown interest, according to a Wall Street Journal report.

But China wants more than just oil from Ecuador and the rest of Latin America. In a June 2012 speech delivered to the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America in Chile, Premier Wen Jiabao said China wants to establish a political and economic partnership with Latin America that is “as strong as the Himalayas and the Andes.”

China is making similar moves around the globe as part of an effort to wean itself off oil from the often-unstable Middle East. But its push into Ecuador and other Latin American countries is of particular concern to some U.S. officials, who fear that it could diminish U.S. influence in a key strategic region in its own backyard, and perhaps someday deprive Americans of an easily accessible supply of oil.

According to State Department cables published by the WikiLeaks organization, Washington has looked on with increasing concern as China focused on Ecuador—and the broader Andean region—as being central to its drive to secure greater oil resources.

In 2006, the U.S. Embassy in Quito noted that China sought to become a “major player” in the Ecuadoran oil industry. Almost overnight, diplomats noted in one cable, “Quito is playing host to a steady inflow of managerial, financial and technical representatives of China’s major and minor oil companies.”

Also, the cable added, “the overseas arms of three major Chinese oil conglomerates [including the China Petroleum Company or Sinopec as well as the Sinochem Corporation]… are present and have ongoing operations in Ecuador.”

In the seven years since, China has sought to cement those oil deals and also to increase its political clout in Ecuador and elsewhere in the region. It has become an important player in the renegotiation of the Quito government’s oil contracts, which increasingly favor state-owned oil companies at the expense of for-profit U.S. multinational corporations that had long done business there, such as Chevron and the Occidental Petroleum Corp. The departure of American investment has created a vacuum for Chinese oil companies to fill.

The Obama administration’s official position is that it is not concerned about Chinese competition in the Latin American markets, including oil.

“We see competition is a healthy thing,” said Heide Bronke Fulton, an official at the U.S. Embassy in Quito. “We believe that U.S. companies will continue to maintain a competitive edge based on the desire for U.S. technology, quality and other factors.”

But others say that, privately, U.S. officials have been concerned that U.S. influence in the region is waning with the exit of these American companies, as well as by Correa’s alliances with the Chinese at a time when he is also pushing away Washington.

Vowing to rid the country of foreign influence in 2009, Correa chose not to renew Ecuador’s 10-year agreement that gave the U.S. use of a military air base in Manta, which was used largely for anti-narcotics efforts in neighboring Colombia. And in April 2011, he expelled U.S. ambassador Heather Hodges after a leaked State Department cable revealed Hodges’ criticism of his government for alleged corruption. The U.S. was without an ambassador to Ecuador for nearly a year. Correa also has beefed up state authority over the oil industry, taking much of the profits and control away from the foreign multinationals.

Taken together, all of these changes could have a significant long-term impact on U.S energy security, according to Roger Noriega, the former assistant secretary of State for western hemisphere affairs.

Ecuador and the Latin America region traditionally accounts for a significant portion of the diversity of U.S oil supply – nearly 20 percent of U.S. imports in 2011. Correa’s oil policies and his decision to embrace China have considerably reduced Ecuador’s output since 2004. As China is strengthening its influence in Ecuador, the United States is losing a natural and convenient energy partner whose potential, experts say, could be further realized by American assistance.

A Changing Tide

While China has showered Correa’s government with attention and money, Latin America “has not been a priority for U.S. foreign policy for many years” because of American preoccupation with the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, said David Goldwyn, former State Department special envoy and coordinator for international energy affairs, in testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 2006.

Others say the U.S. has had little choice, given the Bolivarian Revolution, led by Hugo Chavez, Venezuela’s popular and anti-Western president since 1999, which has brought sweeping socialist reforms to the region. Chavez’s fervent nationalist ideology and denunciation of U.S. influence has spread to other leaders throughout the region.

Ecuador is emblematic of Chavez’s influence. Since 2009, Correa has closely aligned himself with Chavez, similarly using anti-American rhetoric to denounce U.S. influence and appeal to voters, and using social programs and infrastructure improvements built by oil revenues to ensure his popular appeal. Correa was re-elected in February, winning over 50 percent of votes.

Correa’s nationalistic attitude has bled into Ecuador’s energy policies. In 2007, Ecuador announced that the government would receive 99 percent of the oil windfall profits, which occur when the price of oil rises above the price set in the company’s contract. Previously, oil companies shared windfall profits with the government in a 50-50 split. The bigger cut gave Quito a stronger grasp on the energy sector and brought more money into the hands of the government.

In 2010, Correa established a new hydrocarbon law that ended the production-sharing contracts with foreign oil companies. The Ecuadoran government, now complete owner of underground oil resources, rents out blocks for exploration and production in service contracts. The state demands an initial payment of 25 percent of gross revenues as a “sovereign margin.”

As a result, companies no longer benefit from increases in the price of oil, said David Mares, of the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy at Rice University’s Institute for Public Policy. “Correa essentially eliminated that possibility,” he said.

Correa’s changes to the oil sector came on the heels of similar reforms in Venezuela, the largest crude oil exporter in the Western Hemisphere and one of the biggest oil suppliers to the United States. In 2006, Chavez increased the national oil company PVDSA’s share in oil projects to a minimum 60 percent. By 2009, PVDSA had taken control of all of Venezuela’s oil fields.

These reforms have made Ecuador unattractive to American investors. Many U.S. firms have been discouraged to invest in Ecuador, especially after an Ecuadorean court ordered American oil giant Chevron to pay an $18 billion compensation to native tribesman for allegedly dumping toxic oil waste into Amazon for more than 20 years.

A New Player In The Region

Historically, China had been reluctant to engage with Latin America because it had been considered a U.S.-dominated region, said Eric Farnsworth, vice president of the Americas Society/ Council of Americas and a former State Department official.

But, he said, “They’ve found out that there really is ample room for them to expand their operations and I think that’s what they’ve been doing.”

As a result China has aggressively moved in to Latin America, gaining an economic upper hand and political influence in the region.

China’s economy is expected to surpass the U.S.’s by 2030, according to “Global Trends 2030,” a December 2012 report by the National Intelligence Council. As its economy swells, China is turning to Latin America and Africa to secure future oil resources.

In January 2012, China committed to loan another $1 billion to Ecuador, adding to the billions the government had already borrowed from China, largely in exchange for future oil exports.

“Obviously it has been the government’s priority to work with the Chinese,” said Shamim Kazemi, an economics officer at the U.S. Embassy in Quito. “Part of it is geopolitical reasons and political affinity.”

China’s movement into Ecuador is emblematic of its growing interests throughout the continent. In May, Venezuela’s Congress approved a measure to allow the government to borrow as much as $8 billion from China in exchange for oil. A similar deal has been made in Brazil, where state oil company Petrobras also signed a deal with the Chinese company Sinopec in 2010 to develop the country’s oil reserves.

Latin America is turning to China in large part to become less reliant on the U.S. economy and imports.

The U.S. remains “Ecuador’s largest crude oil customer,” according to the U.S. Energy Information Association, but since China and Ecuador began making loan agreements for oil in 2009, an increasingly large share of Ecuador’s oil is heading to China.

“The Chinese tend not to get involved in local politics,” and are “certainly not trying to reform anyone’s domestic politics or economy,” Farnsworth said. “Because of that they have a different profile in the region than perhaps the US or other countries.”

While U.S. officials such as Bronke Fulton of the U.S. Embassy say “there is room for both” the U.S. and China to tap into Latin America’s energy resources, some argue that China will eventually overcome the U.S. as the major player in the region.

Farnsworth noted that U.S. leverage in the form of financing from the International Monetary Fund and other similar institutions may be waning. He said Latin American countries “may not require loans from those entities” because they “can get the support from financing needs from places like China.”

At the same time, as the Chinese invest in Latin America, they are not leaving behind the same kind of infrastructure and technology that U.S. and other private companies used to, Noriega said, adding that that could lead to further instability in these countries.

“[Ecuador] ha[s] rolled out the red carpet for China to take half their production and not put the kind of investment, infrastructure, on the ground that would help the Ecuadorean people develop the full investment of that sector.”

While some argue that the Chinese are not politically motivated, others point to growing ties between China and Latin America outside of the economic sector that might suggest otherwise.

In November 2010, People’s Daily, China’s Communist Party newspaper, reported that Bingde Chen, a senior People’s Liberation Army of China official, met with Ecuadorean Defense Minister Javier Ponce in Quito. Chen “said China pays great attention to the development of Sino-Ecuadorean military ties and would like to deepen bilateral military cooperation and relations on a mutually beneficial basis.” Chen also traveled to Venezuela and Peru on his trip.

Many experts believe that the growth of shale gas in the North America will allow the U.S. to look inward for energy rather than rely on oil from foreign sources. But, others say the U.S. should not turn away from Latin America as an energy partner. Instead, it should have a much bigger presence in Ecuador and the rest of Latin America.

Meanwhile, Latin America, home to some of the world’s biggest oil suppliers and fastest growing economies, is now a major global power that is increasingly projecting its economic and political power while seeking more and more independence from the United States, according to Farnsworth.

China, realizing the shifting the tides, wants Latin America countries to be strong allies. In his speech, Premier Wen said China wanted the total bilateral trade to exceed $400 billion in the next five years.

China’s investment in the region pays off handsomely, according to Paulina Durango, a Quito lawyer representing Ecuador in negotiations of infrastructure projects with China.

“I see how Ecuador is looking to China,” she said. “China is having a gate opened not only in Ecuador but in Latin America.”

U.S. officials and Ecuadorean scholars say China’s presence has changed the game and the United States needs a different approach to re-engage the region. Yet, the State Department doesn’t really have a comprehensive policy to do that, Noriega said.

Farnsworth said more cooperation in the energy sector is the key to a new strategy because the United States offers knowledge and understanding of the energy market that is crucial to the hemisphere’s future.

“We have taken it (Latin America) for granted for far too long,” he said. “I’d like to contend for the region. I’d like to fight for it.”

Saudi Arabia

In 2005, President George W. Bush walks hand-in-hand with Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Abdullah bin Abdulaziz at Bush’s ranch in Crawford, Texas. The image has become a symbol of the exceptionally close bond between the two countries created because of oil. Source: The White House

Aboard the U.S.S Quincy cruiser on Feb 14, 1945, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ensured King Abdul Aziz that the U.S. would militarily protect Saudi Arabia in return for access to its oil, and the “special relationship” between the two countries was born.

Now, 67 years later, oil continues to bind the U.S. to Saudi Arabia, despite underlying tensions regarding terrorist financing in the Middle East kingdom and fundamental differences in policies between the two countries on everything from crackdowns on democratic practices to the treatment of women.

Saudi Arabia, home to one-fifth of the world’s proven energy reserves, was the second largest supplier of oil to the U.S. in 2011. The U.S. imported 1.2 million barrels of oil a day from Saudi Arabia that year and has been increasing its dependence on the country’s oil supplies since 2008, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Throughout history, Saudi Arabia’s vast energy reserves have given the monarchy a unique role and exceptional leverage over the U.S. government and its policies.

Prince Bandar bin Sultan, Saudi ambassador to the United States from 1983 to 2005, was known to conduct bilateral diplomacy in the White House with the president and his top advisers, said Lee Wolosky, former director of transnational threats on the National Security Council. Bandar’s privileged relationship with U.S. government officials was “unlike any other relationship with any other country,” Wolosky said.

The problem has been that the close bond based on oil has placed restraints on other issues in the bilateral alliance between the U.S and Saudi Arabia, he said.

“You are really restrained in your ability to have a hawkish policy in other areas, like terrorist finance to give you an example, if you are dependent on the Saudis for oil,” Wolosky said.

Critics, including some in Congress, have long argued that only when the U.S. reduces its dependence on Saudi oil can it truly be free to push for substantive reforms in the oil rich monarchy.

“If we are serious about energy independence, then we can finally be serious about confronting the role of Saudi Arabia in financing and providing ideological support for al-Qaida and other terrorist groups,” said Sen. John Kerry, D-Mass, during his bid for president in 2004.

Complexities underlying bond between the U.S. and Saudi Arabia were thrust into the spotlight in 2001 when it was reported that 15 of the 19 of the hijackers in the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks were Saudis.

“Fund-raisers and facilitators throughout Saudi Arabia and the Gulf raised money for al-Qaida from witting and unwitting donors and divert funds from Islamic charities and mosques,” according to the 9/11 Commission. Yet, the commission “found no evidence that the Saudi government as an institution or individual senior officials knowingly support or supported al Qaeda.”

Since 2004, the Saudi monarchy itself has been a target for al-Qaida attacks. The Riyadh government has cooperated with the U.S. in making some reforms to combat global terrorism, but privately, U.S. officials have continued to complain that the royal family hasn’t cracked down on terror financing and that it is still rampant in the country.

In a 2009 cable leaked to Wikileaks, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton wrote, “While the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia takes seriously the threat of terrorism within Saudi Arabia, it has been an ongoing challenge to persuade Saudi officials to treat terrorist financing emanating from Saudi Arabia as a strategic priority.”

The leaked State Department cables also reveal the Saudi government’s sensitivities to criticism by the U.S. government.

In 2010, the U.S. Travel Services Administration placed Saudi Arabia on a list of countries whose departing travelers require extra screening after the attempted 2009 Christmas Day bombing on a flight from Amsterdam to Detroit.

In response, Saudi Deputy Foreign Minister for Multilateral Relations Prince Turki bin Mohammed said, “he was very disappointed by the designation of Saudi Arabia as a country of interest, which makes Saudi Arabia feel and look like a ‘black sheep,’” according to the cable.

The cracks in the seemingly unbreakable oil bond extend beyond the issue of terrorist financing. In a cable to Secretary Clinton prior to a visit to Saudi Arabia in February 2010, Ambassador James Smith pointed to “the status of women, religious freedom and human rights” as “ongoing concerns” for U.S. officials.

As the Arab Spring spread across the Middle East in 2011, the Saudi monarchy responded by introducing new laws criminalizing freedom of expression and assembly, according to Human Rights Watch. Seeking to suppress public condemnation of the government, the monarchy also increased censorship of the media.

In Saudi Arabia, Islamic customs require that women have male guardians, who decide whether they are allowed to travel, study or work, according to Human Rights Watch. Similarly, women are not allowed to drive or vote.

Yet, “the US failed to publicly criticize Saudi human rights violations or its role in putting down pro-democracy protests in neighboring Bahrain,” the human rights organization said. “U.S. President Barack Obama failed to mention Saudi Arabia in a major speech on the Arab uprisings and continued to pursue a $60 billion arms sale to Saudi Arabia, the biggest-ever US arms sale.”

Algeria

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton greets President Abdelaziz Bouteflika during an October 2012 visit to Algeria. The U.S. continues to foster close relations with Algeria despite its record of corruption and human rights abuses. Source: U.S. Embassy Algeria

Algeria exports nearly 2 million barrels of oil a day, with about 25 percent of it going to the United States, the first country to invest in the North African nation’s hydrocarbon sector after a 2005 liberalization law allowed foreign investments.

The Obama administration is building stronger economic ties with Algeria by encouraging U.S. companies to do business in the country under the National Export Initiative, which seeks to double U.S exports globally by the end of 2014. Algeria, holding the 14th largest oil reserve worldwide, is already an active market for U.S investors, who dominate the country’s oil and gas sector.

However, corruption is a serious problem in the OPEC member country and the U.S. government is well aware of it. A 2010 State Department cable obtained and published by Wikileaks said former Minister of Energy and Mines Chakib Khelil was responsible for the widespread “culture of corruption” in the state oil company Sonatrach, whose senior executives were investigated for corruption by Algerian authorities in the same year.

The investigation led to the removal of the Sonatrach’s chief of executive, Mohamed Meziane, and a dozen senior officials. The cable alleged that Reda Hemche, Khelil’s protégé and Sonatrach’s former chief of staff, was responsible for the corruption deals that shook the country’s oil sector.

Algeria also has a poor human rights record. It strictly restricts the freedom of assembly, discriminates against women, carries out torture and arbitrary killings and, during the Iraq war, was one of the largest suppliers of anti-coalition fighters, according to a 2012 report by the Congressional Research Service.

Despite these problems, the U.S. government is fostering closer ties with Algeria. The country, in addition to the oil deals, is also in a position to provide crucial assistance to U.S. regional counterterrorism activities because of its strategic location and influence, especially as the Obama administration steps up efforts to fight groups with ties to al-Qaida in North Africa after Secretary of State Clinton linked them to the Benghazi attack that killed U.S. ambassador Christopher Stevens.

The U.S. has tried to balance appreciation for Algeria’s contributions to counterterrorism with calls for political reform while expressing support for the Algerian government led by President Abdelaziz Bouteflika. In 2011, Bouteflika lifted a 19-year state of emergency that authorities said helped them combat Islamist extremists, but that critics said was used to repress political opponents.

The ban was lifted after Algeria faced waves of social protests similar to those that toppled regimes in Egypt and Tunisia in the so-called Arab Spring. Clinton called for greater political freedom in Algeria when she visited the region in 2011.

In his Senate confirmation hearing in 2011, U.S. Ambassador to Algeria Henry Ensher said he would prioritize outreach to the country’s people while deepening counterterrorism cooperation and economic ties. Algeria receives foreign aid assistance under the State Department’s Middle East Partnership Initiative, which was designed to help citizens in the Middle East and North Africa build more “pluralistc, participatory and prosperous” societies.

In March 2011, a U.S.-Algerian counterterrorism contact group was launched to share intelligence information, and Algeria receives U.S. assistance to strengthen its capacity to fight al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb, the regional affiliate of the terror network.

Equatorial Guinea

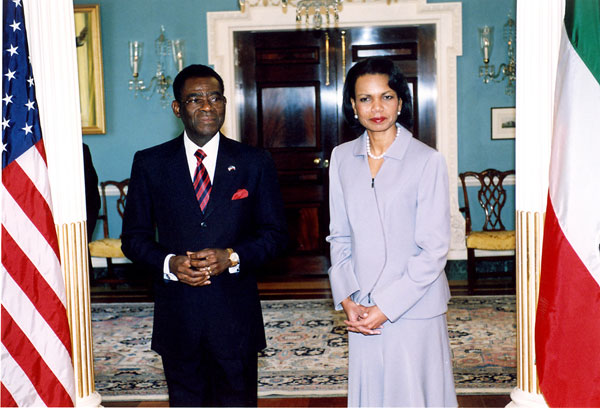

Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice greets Equatorial Guinea’s President Obiang Nguema Mbasogo in April 2006 at the White House. Rice tells Obiang,”You are a good friend and we welcome you,’’ despite well-documented entrenched corruption issues and serious human rights abuses in Equatorial Guinea. Source: State Department

American oil companies have invested almost $14 billion in the Republic of Equatorial Guinea since the 1995 discovery of the Zafiro oil field off the shores of this once isolated and impoverished West African country. They are now responsible for nearly all of its oil production.

Equatorial Guinea has become the third largest oil producer in sub-Saharan Africa and an important energy ally of the United States. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the United States was the top destination for Equatorial Guinean oil in 2010, accounting for 29 percent of total exports.

The country is also strategically located in the Gulf of Guinea. The U.S. imports 12 percent of its oil from African oil producers in the region, according to U.S. Ambassador to Equatorial Guinea Mark L. Asquino.

A 2009 State Department cable obtained and published by Wikileaks said that U.S. energy strategy would have a “gaping hole” if it ignored Equatorial Guinea, whose light, sweet crude oil is highly prized in international markets.

But Equatorial Guinea has been plagued by official corruption ever since the sudden flush of oil wealth. The country’s lawlessness exacerbated the problem. President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, who has ruled Equatorial Guinea for almost 40 years, and his family have amassed billions of dollars while the majority of Equatorial Guineans live on less than $2 a day.

The corruption problems attracted widespread attention when the U.S. Justice Department alleged that Obiang’s son, Teodoro Nguema Obiang, had been laundering money in America. Prosecutors went to court in 2011 to seize $70 million of his assets, which included a $30 million Malibu mansion and $2 million in Michael Jackson memorabilia. Seven years earlier, a Senate investigation exposed the Obiangs’ secret accounts at Riggs Bank in Washington, which paid $16 million in fines for failing to report suspicious activities in the scandal that involved both the former Chilean Dictator Augusto Pinochet and President Obiang.

In August 2012, French police seized a five-story Paris pied-a-terre and 11 luxury cars belonging to the 43-year-old son following a corruption investigation involving President Obiang.

The State Department has tried to paint a rosier picture of the elder Obiang. Other 2009 cables said that Equatorial Guinea is “no worse than many of America’s energy allies” and that hundreds of millions of dollars are going into social spending in the country. According to Ambassador Asquino’s 2012 statement to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, the government is considering applying to be a candidate for the Britain’s Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative again after it failed to meet the requirements in the first application. The anti-corruption Program, which makes countries eligible for foreign aid, was announced in 2002 by then-British Prime Minister Tony Blair at the World Summit on Sustainable Development.

Equatorial Guinea is also notorious for its poor human rights record. Torture at prisons is systematically carried out despite laws forbidding it. A 2011 State Department human rights report said that the government was “intolerant” of critical views and maintained a “monopoly” over political life.

But the United States has been cautious in forcing Equatorial Guinea to tackle its problems; critics say that is to avoid potential fallout with the country’s leaders. The Obama administration is encouraging an evolving fiscal transparency instead of calling for the kind of immediate changes that the Wikileaks cable said could place the state in turmoil.

“Do we want to see the country continue to evolve in positive ways from the very primitive state in which it found itself after independence? Or would we prefer a revolution that brings sudden, uncertain change and unpredictability?” one State Department cable asked. “The former is clearly the path the country is on, and the latter has potentially dire consequences for our interests, most notably our energy security.”

The cable went on to say that Equatorial Guinea was reaching out for U.S assistance and called for a more appropriate guiding narrative for the relationship with this country.

“EG’s hand is not clenched in a fist,” it said. “It is reaching out for our assistance. Our own history has taught us that aiding those who ask for help can heal historical wounds and promote integration. This is a story we must tell again.”

Azerbaijan

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton talks to Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev at the presidential residence in Baku during a July 2012 trip. While in Azerbaijan, Clinton attended an oil and gas conference and pushed Aliyev to carry out human rights reforms, which have also long been a source of U.S. concern. Source: State Department

Since Azerbaijan gained independence after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the U.S. relationship with the largest country in the Caucasus has revolved around its vast energy reserves. In 1997, Azerbaijan President Heydar Alyev made his first official trip to the U.S. to meet with President Bill Clinton and to sign production agreements with four major US companies: Chevron, Exxon, Mobil and Amoco.

With an estimated 7 billion barrels of proven oil reserves today, Azerbaijan remains a close partner on energy issues with the U.S., despite significant documented human rights abuses and corruption accusations against the government. In 2003, Aliyev was succeeded by his son, Ilham.

U.S. imports of crude oil from Azerbaijan began to increase significantly in 2002, peaking in 2009 at 75,000 barrels per day, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. While exports from Azerbaijan have decreased since 2009, the country remains a crucial supplier of oil to the U.S. The United States imported 7.78 million barrels of oil from Azerbaijan between January and August 2012.

Understanding the vast potential of the Caspian region’s oil reserves, the U.S. exerted its influence in the early 1990s to ensure that Russia would not control the energy resources of the region’s newly independent countries, including Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

The U.S. believed that “those that are blessed with energy resources ought to have an opportunity to produce and export them without having to obey Moscow’s dictate,” said Cory Welt, associate director of international relations at the Institute for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies at George Washington University.

Today, U.S. interest in Azerbaijan also lies in the country’s unique position to ensure European energy security by diversifying the oil and natural gas market for Europeans, who previously relied heavily on Russia.

“We want to assist Europe in its quest for energy security,” said Richard Morningstar, then- special envoy for European Energy before a House Foreign Affairs Committee in June 2011. “We have an interest in an economically strong Europe…so our aim is to encourage the development of a balanced and diverse energy strategy with multiple energy sources and multiple routes to market—a competitive, efficient market which offers the best prices for consumers.”

Yet, the oil-rich authoritarian government has long been criticized for human rights abuses and anti-democratic practices. Aliyev has placed significant restrictions on the freedom of speech and freedom of assembly of his people, Welt said. “You can get locked up for saying negative things about the government and people do.”

But, in 2006, Matthew Bryza, then deputy assistant secretary of state for Europe and Eurasian affairs and later ambassador of Azerbaijan, told NPR, “We don’t see Ilham Aliyev as a dictator. We see him as a leader of a country with an emerging democracy that has a long way to go.”

The human rights situation in Azerbaijan has recently worsened, according to Human Rights Watch’s 2012 World Report and U.S. State Department cables released by Wikileaks.

“Azerbaijan’s already poor democracy and human rights record is worsening, with media freedom deteriorating and a general disregard for freedoms of assembly and speech,” wrote Robert Gaverick, a former political-economic section officer at the U.S. Embassy in the capital of Baku, in a 2010 cable.

The cable stressed the need to promote democratic reforms in the country to protect U.S. interests. “Azerbaijan continues to be a strategically important country for the United States, particularly in terms of security cooperation and energy resources,” Gaverick wrote. “These developments, in our view, threaten the long-term stability of the country, and eventually could put other areas of cooperation at risk.”

Also, the vast oil revenues and lack of transparency has fueled corruption in the government. In 2012, Azerbaijan received one of the lowest Corruption Perception Indexes by Transparency International, ranking 139 out of 183 countries.

Despite these concerns, the U.S. continues to cultivate its relationship with Azerbaijan around energy issues. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton traveled to Azerbaijan in July 2012 and one of her primary stops was at the Caspian International Oil & Gas Exhibition, which was organized by a British and an Azerbaijani oil company.

A report from the exhibition, where experts discussed the country’s energy sector and leaders courted foreign investment., concluded that both President Barack Obama and British Prime Minister David Cameron “sent greetings and dignitaries” and “emphasized Azerbaijan’s key role in creating new energy corridors and the need to develop a closer relationship between Azerbaijan and their respective countries.”

During her visit, Clinton also stressed the need for further democratic reforms in the country so thatr the two countries can remain close partners in the future.

“We, as we always do, urge the government to respect their citizens’ right to express views peacefully, to release those who have been detained for doing so in print or on the streets or for defending human rights,” she said during remarks with Azerbaijani Foreign Minister Elman Mammadyarov.