- ← Domestic sources integral to U.S. energy security, but may be vulnerable

- Vulnerabilities pose risks in top U.S. oil suppliers →

Strategic Petroleum Reserve: A hedge against shortages

Introduction

Created in 1975, two years after the Arab oil embargo, the Strategic Petroleum Reserve is designed to be the U.S. insurance policy in case of an oil shortage that rises to the level of a national security emergency. The SPR consists of four facilities on the Gulf Coast that can hold a combined 727 million barrels of crude oil. The U.S. currently has 694.9 million barrels of crude oil stored in the SPR’s naturally occurring salt domes in Texas and Louisiana, enough to replace current net oil imports for about 82 days.

Since its inception, one of the original tenets of having a strategic stockpile was that its existence would discourage the use of oil as a political weapon. The embargo imposed by Arab oil producers was intended to create a very discernible physical disruption; in fact, the result was long lines of cars at the gas stations in the U.S. in the early 1970s.

“The genesis of the SPR was focused especially on deliberate and dramatic physical disruptions of oil flow, and on blunting the significant economic impacts of a shortage stemming from international events,” according to a report by the Congressional Research Service, the independent research arm of Congress. The Arab oil embargo also was the impetus for the establishment of the International Energy Agency, a group of 28 member countries that maintain their own emergency reserves in order to respond to energy crises.

The SPR has an estimated value of $64 billion in crude oil, and the U.S. has invested $23.3 billion over time to build and maintain the emergency reserves.

The president has the authority to tap it only in the case of a “severe energy supply interruption,” according to legislation, which has occurred under these findings only three times over the past 36 years. President George H.W. Bush ordered the first release in 1991 at the beginning of the first Gulf War. President George W. Bush ordered the second release in 2005 after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita caused damage to the oil industry. And finally, the third was in 2011 when President Barack Obama ordered a drawdown as part of a coordinated IEA drawdown in response to the shutdown of Libyan oil exports.

The Energy Policy and Conservation Act says the reserve should be used only to ameliorate discernible physical shortages of crude oil, although the meaning of law’s language has been debated. Its use, cost and policies have inspired heated arguments in Congress and elsewhere over its purpose and its management, with critics noting that in today’s global economy the U.S. can buy oil on the open market. In addition, some question whether a stockpile of emergency fuel is necessary if the government is using other means to intervene in oil markets. For example, a Foreign Policy article noted, “Every president since Ronald Reagan has used Saudi Arabia as his de facto SPR” and that for decades, the U.S. presidents have been able to rely on Middle Eastern producers to pre-release oil in anticipation of times of war.

The reserve facilities are tightly guarded. The Bayou Choctaw facility outside of Baton Rouge, La., has metal fences topped with barbed wire, security posts, armed guards, and multiple “No Trespassing” signs. Treated almost like a nuclear site, according to one former Energy Department official, the SPR is America’s petroleum Fort Knox, patrolled by small armies of private security guards. The Department of Energy has declined to discuss what goes inside the heavily guarded sites.

A reporter from the Medill National Security Reporting Project spent months trying to gain access and had multiple requests denied by the Strategic Petroleum Reserve office, which is part of the Department of Energy. Officials said they were “unable to accommodate requests for a site visit at this time.”

History

History of the Strategic Petroleum Reserve

U.S. Presidents have released oil from the reserve only three times. The first was President George H.W. Bush on Jan. 16, 1991, at the beginning of the first Gulf War. The United States joined its allies in making sure there were enough global oil supplies.U.S. Department of Defense

How It Works

- Bryan Mound holds 254 million barrels in 20 caverns

- Big Hill holds 170.1 million barrels in 14 caverns

- West Hackberry holds 228.2 million barrels in 22 caverns

- Bayou Choctaw holds 73.2 million barrels in 6 caverns

America’s Strategic Reserve of Oil

In case of an emergency disruption to its oil supply, the U.S. has the largest stockpile of government-owned emergency crude oil in the world, which would provide about 82 days of import protection for Americans. But how does the Strategic Petroleum Reserve work?

U.S. emergency crude oil is stored thousands of feet underground in salt caverns, some of them extending a mile beneath the earth’s surface. There are four locations in the Gulf region: Bryan Mound in Brazoria County, TX; Big Hill in Jefferson County, TX; West Hackberry in Cameron Parish, LA; and Bayou Choctaw in Iberville Parish, LA.

Why salt caverns?

They were deemed a more secure, affordable and long-lasting means of storage than above ground tanks. Salt caverns have been used for storage for many years by the petrochemical industry, so the U.S. government acquired previously created salt caverns to store crude oil when they created the SPR.

Why crude oil?

Crude oil is cheaper to acquire, store and transport than refined products. It also doesn’t degrade over time.

Administrative costs?

It costs about $3.50 per barrel stored per year, considerably lower than in Europe and Asia. The U.S. has invested $23.3 billion to build and maintain the SPR, according to government estimates.

How It Is Stored

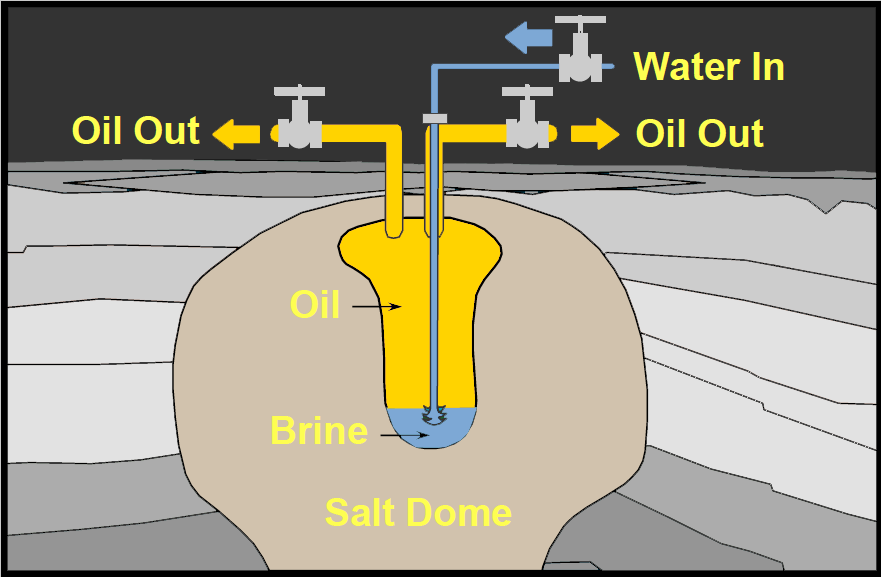

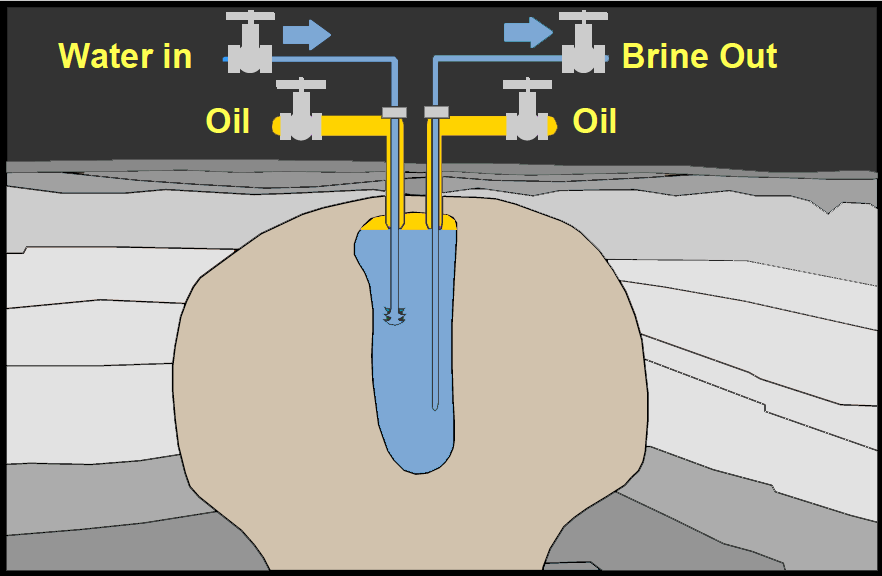

Salt caverns are carved out of underground salt domes by a process called “solution mining.” The process involves drilling a well into a salt formation, then injecting massive amounts of water. The water dissolves the salt. The dissolved salt becomes brine and is piped offshore into the Gulf of Mexico. Oil is then pumped into the caverns.

The oil reserve inventory was 694.9 million barrels as of Nov. 30, 2012

What is the difference between sweet and sour crude oil?

The difference is the crude’s sulfur content. Sweet grades have less than 0.5 percent sulfur, whereas sour crude has a higher level. The SPR holds both sweet and sour crude, and they are contained in caverns designed as either sweet or sour.

Why is there more sour than sweet oil?

The ratio was determined to meet the needs of the U.S. refining industry. Nearly all refiners can process sweet crude oil; the same is not true for sour crude.

Which is more requested?

Sweet crude is mostly requested during times of emergency because of its value to refiners to produce transportation fuels.

![[chart]](../wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Screen-Shot-2012-12-13-at-5.33.38-PM.png)

- Two major types of crude oil: “Sweet” and “Sour” grades

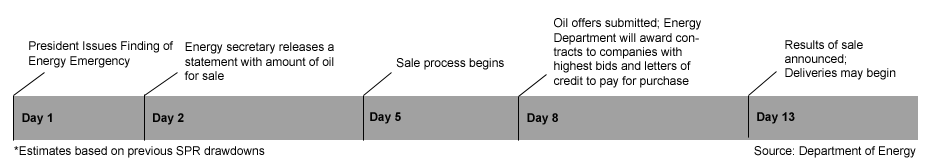

- Maximum drawdown capability: 4.4 million barrels per day

- Time for oil to enter the market: 13 days from presidential decision

- Average price paid for oil in the reserve: $29.76 per barrel

Controversy

Created as a buffer against energy supply disruptions that affect our national security, the Strategic Petroleum Reserve has caused much controversy over the years. Some critics have raised questions about its operations and oversight, including when and how the SPR should be used. Some argue that it should only be tapped during a full-scale national emergency, while others say it should also be used occasionally as a means to alleviate high domestic oil and gasoline prices.

Alvin Alm, the former director of the Harvard Energy Security Program described this controversy in his book, “Oil Shock: Policy Response and Implementation”: “Although almost all energy experts and politicians agree that a Strategic Petroleum Reserve is desirable, serious disagreement exists on the purpose of the reserve and how it should be managed. Some view it as a tool of military and foreign policy, only to be used during periods of dire national security threats. The majority of political leaders and interested citizens view the Reserve as a source of fuel to prevent physical shortages.”

There are a lot of other arguments about the SPR too, including whether it’s even needed, and why taxpayers are footing the bill.

Jerry Taylor, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, co-authored a 2005 report that included that passage from Alm’s book. He and co-author Peter Van Doren also wrote that, “The Strategic Petroleum Reserve has been almost uniformly embraced by politicians and energy economists as one of the best means to protect the nation against oil supply shocks.’’

But, they added, “This study finds little evidence for the proposition that government inventories are necessary to protect the country against supply disruptions. Absent concrete market failures, government intervention in oil markets is unlikely to enhance economic welfare.’’

In an interview, Taylor said the government has misused the reserve, “The history of SPR management is a good example of the inventory being used based on political calculus, not by economic calculus.” He said “politicians are in the business of maximizing political capital” so they will manage the SPR in a way that will get the most political support, unlike private inventory holders that are primarily interested in maximizing profit. This may not be done out of concern for the consumer, but it will have a positive effect on them because private inventory holders will deliver products to the market when they are desired at the time, said Taylor.

And finally, Taylor and Van Doren concluded in their study, the SPR had cost taxpayers at least $41.2 billion by 2004, even though it had only been tapped three times, “and in each of those instances, the releases were too modest and, with the exception of the 2005 release related to Hurricane Katrina, too late to produce significant benefits. Accordingly, the costs associated with the SPR have been larger than the benefits thus far.’’

Others have been far more supportive of the SPR, and say it is a critically important aspect of U.S. energy security.

But even some supporters have concerns.

John Shages, a former deputy assistant Energy secretary for the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, argues that the SPR hasn’t been used to its full potential. “I think the single biggest problem is that the people don’t understand how powerful this thing can be in its actual usage,” in context of balancing out erratic oil price fluctuations, Shages said in an interview.

“Both the law and policy makers have treated the Strategic Petroleum Reserve as an emergency response of last resort. The legal requirement for a Presidential finding to authorization sales is close in concept to a declaration of war. This is unfortunate. If this tremendously powerful tool were more frequently used in response to economic and energy problems our economy and energy security would be tremendously enhanced,” said Shages, now with Strategic Petroleum Consulting LLC.

Amy Jaffe, an energy expert and co-author of “Oil, Dollars, Debt and Crises: The Global Curse of Black Gold,” wrote in Foreign Policy on Aug. 2012 that the U.S. has been “surprisingly reluctant to release SPR during times of crises, preferring instead to let Saudi Arabia handle the problem by simply increasing its production.” For years, the U.S. has relied on Middle Eastern producers to pre-release oil in anticipation of times of war.

There is also confusion and debate over who, exactly, is in charge, thanks to what some critics say is a lack of a comprehensive policy. The President has the primary authority to decide when to use the SPR, according to the Energy Policy and Conservation Act. It authorizes the President to use the SPR in the event of a “severe energy supply disruption” or when the U.S. is required to meet the obligations of the International Energy Agency.

But a Rand Corporation report from 2009 also concluded that U.S. policies governing the use of the Reserve are confusing and ambiguous, therefore reducing its effectiveness.

The Rand report said, the absence of a publicly stated policy on when the SPR will be used “has the potential to trigger panic hoarding if market participants fear a major supply disruption, bringing on the very conditions that SPR use is supposed to ameliorate.”

The report concluded that such secrecy may be necessary. “Policy makers have been reluctant to spell out in advance what would trigger SPR use, since, under current law, this would mean defining in advance what constitutes a national emergency related to oil supply disruptions and what responses would be taken.”

In a 2009 hearing before the U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) was critical of the ambiguity. “We don’t have a policy, a stated policy, as to when the SPR, when there should be a drawdown. As I say, according to this report it creates that same level of uncertainty that we’re looking to ameliorate.” She urged the Obama administration to review the issue.

McKie Campbell, the Republican staff director for the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources who works closely with Sen. Murkowski, said the committee doesn’t have specific recommendations as of now, but there is a “fair chance” that the SPR will be discussed this upcoming session of Congress.

According to a Government Accountability Office report from 2006, the current legislation allows broad presidential discretion and provides only general guidance for the SPR’s use, making use of the SPR a matter of judgment by the President.

“It should be clarified to essentially put more power into the hands of the President, to do it based on circumstances of the time rather than trying to find the situations under which it should be used,” Shages said, referring to the current Energy Policy and Conservation Act. Trying to define specifically what an emergency of a national scope could be difficult. “I think everybody should have realized is now that all these years later, there are events that you can’t foresee for which you could appropriate to use the Strategic Petroleum Reserve,” Shages said.

Also, the Government Accountability Office report said that “the SPR is an extremely valuable asset, and releasing oil from the reserve during oil supply disruptions could greatly reduce the damage to the U.S. economy.” Since oil plays a critical role in the U.S., price increases in products made from crude oil, such as gasoline diesel, home heating oil, and petrochemicals and even fertilizer, can cause serious financial hardship for consumers, thus reducing economic activity. Past studies have shown that oil price shocks in economic damage to the U.S., according to this report.

The Strategic Petroleum Reserve was created to be a buffer; it’s not meant to be a substitute for crude oil in a case of a severe energy supply disruption, said Rep. Glenn Anderson (R-WA). “It can’t prevent the shock that will come. It’s just meant to soften the blow,” Anderson said.

With oil as the largest primary source of energy in the U.S., the Energy Information Administration projects that transportation will comprise an even larger part of the nation’s oil use in the future, about 72 percent in 2030. According to recent EIA data, the U.S.’s transportation petroleum use is 67 percent of total U.S. petroleum use, and about 93 percent of energy used for U.S. transportation comes from oil. The Strategic Petroleum Reserve will still be relevant for many years to come as oil continues to be the defining transportation energy fuel, Anderson said.

“We have no viable substitute for oil and gasoline in terms of transportation at all.” Anderson said. “We’re trying to work on natural gas and batteries, but those have not developed to a scale that they even remotely come close to replacing oil as the primary fuel.”

Community Impact

While the neighbors who live near the Strategic Petroleum Reserve in Plaquemine, La. have heard about the site, many of them aren’t exactly sure what goes on beyond those heavily guarded gates.

Secrecy

Plaquemine, La. — The Department of Energy states that the Strategic Petroleum Reserve is part of the agency’s critical infrastructure and serves as the nation’s first line of defense against an interruption in petroleum supplies and as a national defense fuel reserve. In 2005, the DOE inspector general concluded that “any disruption in the ability of the SPR to provide emergency crude oil may have an adverse impact on the nation’s economy and security.”

The Energy Department is required to ensure that there is adequate security to extract the oil and supply it to commercial pipelines. It is not responsible for security of pipelines beyond the SPR site boundaries.

Each SPR site has a security force managed by Pinkerton Government Services, a subcontractor to the Energy Department’s primary SPR managing contractor, DM Petroleum Operations Co.

Security is extremely tight at all of the Reserve sites. “You have to surpass systems of detection, all sorts of fencing, multi-barrier fencing. You have live individuals who are armed and trained,” said John Shages, a former DOE deputy assistant secretary for the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. The Security Police Officers are “former military, and they go through the same kind of screening that we would put them through if we were hiring for a federal position.’’ The security force at each of the sites also undergoes performance tests involving simulated explosives and helicopters.

I experienced how strict the security was when I visited the Bayou Choctaw site, at the end of a Louisiana highway, in November. It was a heavily guarded fortress. As I walked around the perimeter, there were guards wearing gray Strategic Petroleum Reserve Police Officer uniforms, with bulletproof vests and guns, patrolling in white SUVs. I accidentally took a few steps onto the Reserve property, and they immediately took down my driver’s license information and the license plate number from my rental car.

The use of private contractors for SPR security is not anything new and has “just worked out well in history,” said Shages, who is now the president of Strategic Petroleum Consulting LLC.

The SPR crude oil is stored in deep underground salt domes that minimize access to the oil by potential adversaries, according to SPR officials quoted in the inspector general’s report. The report also noted that the loss of SPR assets, the crude oil, “does not pose grave danger to the public sufficient to warrant the use of deadly force as even a catastrophic event at SPR would have limited effect outside the boundaries of a SPR site.” In addition, the report said there was no feasible way for an opponent to steal sufficient quantities of oil to significantly endanger the public or environment.

International Energy Agency

Since 1974, the United States and 27 other nations have become members of the International Energy Agency. The founding treaty called the International Energy Program (I.E.P. Agreement) obliged all member countries to maintain reserves of oil or petroleum products equaling 90 days of net imports and to release these reserves and reduce demand during oil supply disruptions. The agreement also created solidarity between the members, which means that if one or several member countries are confronted with a sudden supply disruption, all member countries would take collective action by making oil available from their reserves and reducing demand. For example, during the shutdown of Libyan oil exports in 2011, 28 member countries agreed to make 60 million barrels available to the oil market from the emergency stockpiles of eight larger IEA countries.

IEA member nations fulfill this obligation in various ways; some countries require that private companies hold reserves, others, like the United States, have created government reserves, and some countries hold a combination of the two. Some IEA countries hold refined products in addition to crude oil reserves while the U.S. holds only crude oil. In November 2012, the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve contained 694.9 million barrels, equal to about 82 days of estimated fuel consumption. In addition to government reserves, private industry inventory of crude oil and petroleum products varies over time, but recent U.S. Energy Information Agency data shows that industry stocks increase the days of U.S. protection to 171 days. Thus, at the current level of oil demand, the SPR combined with private industry holdings contains enough oil and petroleum products to exceed the United States’ 90-day reserve requirement.

The 28 member countries of the International Energy Agency are Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Republic of Korea, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic (Slovakia), Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom and United States.