What the 1916 NYC Polio epidemic can tell us about COVID-19

This graphic features the design of a cardboard placard (sign) that was placed in windows of residences where patients were quarantined due to poliomyelitis.(MNS/Piper Hudspeth Blackburn)

and BRIAN JOHNSON

As the weather warms up, New York City residents are preparing for a different sort of summer season this year. From closed movie theaters, to canceled festivals and shuttered storefronts, concerns about COVID-19 infection have brought much of the city to a halt. More than a century ago, however, a different virus was keeping some city residents indoors.

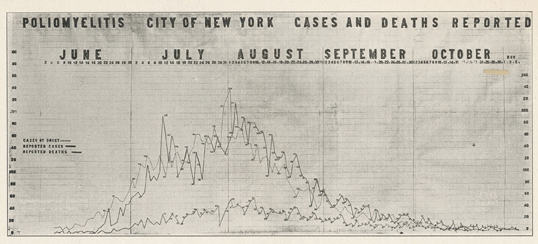

In 1916, a polio epidemic spread, infecting an estimated 25,000 people, killing around 5,000 in the United States, and infecting 6,000 and killing 2,000 in New York City alone. Though anyone could contract the virus, children were more at risk.

While the 1916 outbreak was not the first spike of polio cases in the 20th century, it was the largest outbreak of polio ever seen up to that time, and public reaction had much in common with the current COVID-19 pandemic. Both led to similar quarantine practices in New York City, both viruses could be spread by people with little to no symptoms, and little was known about treatment in either case.

However, there are some stark differences to note. The novel coronavirus pandemic is global, while the polio outbreak of 1916 was concentrated in the northeastern United States, specifically in New York. The epicenter of the polio epidemic was Brooklyn and the amount of polio infections declined uniformly as the pandemic spread from its origin. Still, the steps taken to slow the spread reveal enduring challenges a city faces when waging war with a deadly virus.

Slowing the spread is nothing new

“Do not let your child go to parties, picnics, or outings,” warned a leaflet issued to parents by the New York Department of Health.

Quarantine placards were placed on the homes of the infected In communities outside the city, signs barred children under 16 from entering into town. The New York Police Department also revoked licenses for some neighborhood Independence Day celebrations. As late as the 1950s, pools, amusement parks, and other public spaces could be closed due to fears of polio.

Much like today, local authorities closed schools to slow the spread of infection. Some parents had advocated for the start of school to be delayed and had even threatened to take legal action to prevent the schools from opening too early. The start of school was delayed for over two weeks. Colleges were affected too. Princeton University, for example, delayed the start of its fall classes, as did Cornell University and the College of the City of New York.

Sports were also affected by the polio epidemic: the first football game of the year at the US Military Academy at West Point was played without spectators.

Life during the NYC polio outbreak

Many New Yorkers saw staying home as the only way to protect themselves from the virus. In the summer of 1916, Louis Eisner, a 26-year-old businessman and professional photographer, owned a 600-seat movie theater in Brooklyn. He had to close soon after the outbreak.

“Children were dying and the only thing doctors could say was to keep children out of crowds and stay home to avoid contagion,” he wrote in a letter to family members about the outbreak 50 years later.

The polio epidemic changed other aspects of his daily life, as he spent money buying better-graded milk for his infant son at the time, and even went so far as to leave the child outside for extended periods.

“The idea was fresh air keeps the baby healthy,” Eisner explained. “So we kept him packed like a little red-cheeked doll. His nose looked frozen, but the rest of him was warm.”

A popularly held idea in the 19th century was that foul smelling air, known as miasma, could carry and transmit diseases. Even though medical professionals dismissed the idea, many people still believed it in the early 20th century.

Alvah Doty, a former Health Officer for the Port of New York, wrote in a letter to the editor of the New York Times in July, 1916, “The theory that infectious organisms are transmitted through the medium of air… is erroneous and without scientific or reasonable foundation.”

Doty continued, “I believe that this erroneous theory has been largely responsible for outbreaks of infectious diseases, for it has masked the true media of infection.”

Protests and poor information

Today, the COVID-19 pandemic has prompted a wave of misinformation, aided by social media, sometimes leading to deadly results. In 1916, false theories about the virus spread, creating an uproar in the community of Oyster Bay, Long Island.

Oyster Bay residents protested against polio regulations, including a regulation that allowed health officials to remove and isolate children suspected of having polio from their families. During a town meeting, a resolution was drafted which downplayed the significance of the virus and criticized John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie for their funding of research into the viruses, and the public health officials for creating a “state of terror.”

As a result of the town meeting, the citizens were able to get the measures to prevent the spread of polio removed. However, Oyster Bay witnessed an extremely high rate of polio infection, over five times the rate of New York City.

Immigrant groups were targeted. Some claimed that Polish and Italian immigrants, who resided in crowded tenements, were responsible for the spread due to their supposed lack of hygiene. There are parallels today. An explanation put forward for the origins of the virus held that immigrants from Italy brought it to New York City, but there is no evidence to support that claim.

In the summer of 1916, residents of Woodmere, Long Island, protested the building of a hospital in their town that would house polio patients, based on fears that it would lead to the spread of polio. In a town meeting, officials approved an order that would prevent polio patients from going to the hospital other than cases that originated in or around Woodmere, which only had one case at the time. Even after that order passed, people still feared that polio patients from elsewhere on Long Island would be taken to the hospital.

That didn’t satisfy panicked residents. One day that summer, when hundreds of demonstrators gathered and threatened to burn down the hospital, New York City detectives stood guard and blocked them, warning they would shoot if the protesters tried to approach the building. Complicating the standoff, Nassau County deputy sheriffs had joined the local residents and said they would shoot anyone who tried to bring a patient to the hospital. Violence was averted, but polio patients had to be treated at another Long Island facility.

A roadmap for dealing with COVID-19

A year after the start of the 1916 outbreak, the New York Department of Health grappled with how to deal with a future outbreak.

“We must, until new information is forthcoming, rely upon early diagnoses, prompt notification, hospitalization or equivalent home isolation, a well informed public and an alert medical profession,” said a report.

Now, in the age of COVID-19 public health specialists and politicians champion the practices of diagnoses, isolation, and clear messaging.

For instance, the state of New York has revealed plans to do extensive testing and provide healthcare services in public housing communities, while encouraging residents to stay home to stop the spread of the virus.

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, who has become prominent for his daily discussion on the virus said it would not be easy to return to normal.

“Any plan to start to reopen the economy has to be based on data and testing, and we have to make sure our antibody and diagnostic testing is up to the scale we need so we can safely get people back to work,” he said.

It’s worth noting that it took almost 40 years to solve the threat of polio when Dr. Jonas Salk completed trials for his polio vaccine which began to be distributed worldwide in 1955. Researchers around the world are working 24/7 to find a vaccine for COVID-19, with hopes that they can produce a workable vaccine in less than two years.