Mission creep a way of life in Western Pacific

7th Fleet worked to dangerous exhaustion

By Oyin Falana

ABOARD THE USS RONALD REAGAN — Capt. Michael “Buzz” Donnelly is commander of one of the most in-demand warships in the world.

The only forward deployed aircraft carrier here in Yokosuka, Japan, the Reagan patrols a vast area marked by growing friction driven by an unpredictable leader in North Korea, occasional Russian provocations and a regime in China that in recent years has been seizing and militarizing disputed South China Sea territories.

The escalating tensions spurred a surge in missions for 7th Fleet ships. From 2015 to 2016, according to Navy statistics, the number of days 7th Fleet cruisers and destroyers spent underway soared by 40 percent, from 116 days at sea to 162 days.

Donnelly said he has not refused a request, but sometimes has to manage his superior’s expectations, “very rarely to the detriment of accomplishing any mission.”

“There’s an expectation based on capabilities that sometimes just can’t be met because of real-world constraints,” he said during a recent interview here shortly before the Reagan returned to patrol following several months of scheduled maintenance.

The increased underway time is largely to meet mission requests by the combatant commanders who oversee U.S. military operations by region and answer to the Secretary of Defense. Until 1986 – and passage of the Goldwater-Nichols Act, that authority was held by the leaders of the individual service branches, who some argue are in better position to match mission to resources.

Retired admiral Gary Roughead, former Chief of Naval Operations, said in an interview that it’s long past time to review the act and restore some operational authorities to the service chiefs.

“Anytime there’s been a policy for [32] years, it’s not a bad idea to go back and look at it again because so much has changed,” he said.

Data on the number of combatant commander mission requests – much of which is classified – is not available, but experts say they soared after the terror attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

Ship commanders can go through their superiors to seek to deny requests, but doing so runs counter to the can-do spirit the Navy prides itself on.

At-sea collisions last summer that cost the lives of 17 sailors aboard two Yokosuka-based destroyers served as a tragic wakeup call to the hectic pace of the 7th Fleet and the toll it was taking on people and ships.

Those collisions also led to the firings and early retirement of several top Navy officers in the Pacific, including the former head of the 7th fleet, who were tasked with balancing mission requests against the need to ensure that ship training and maintenance requirements were met.

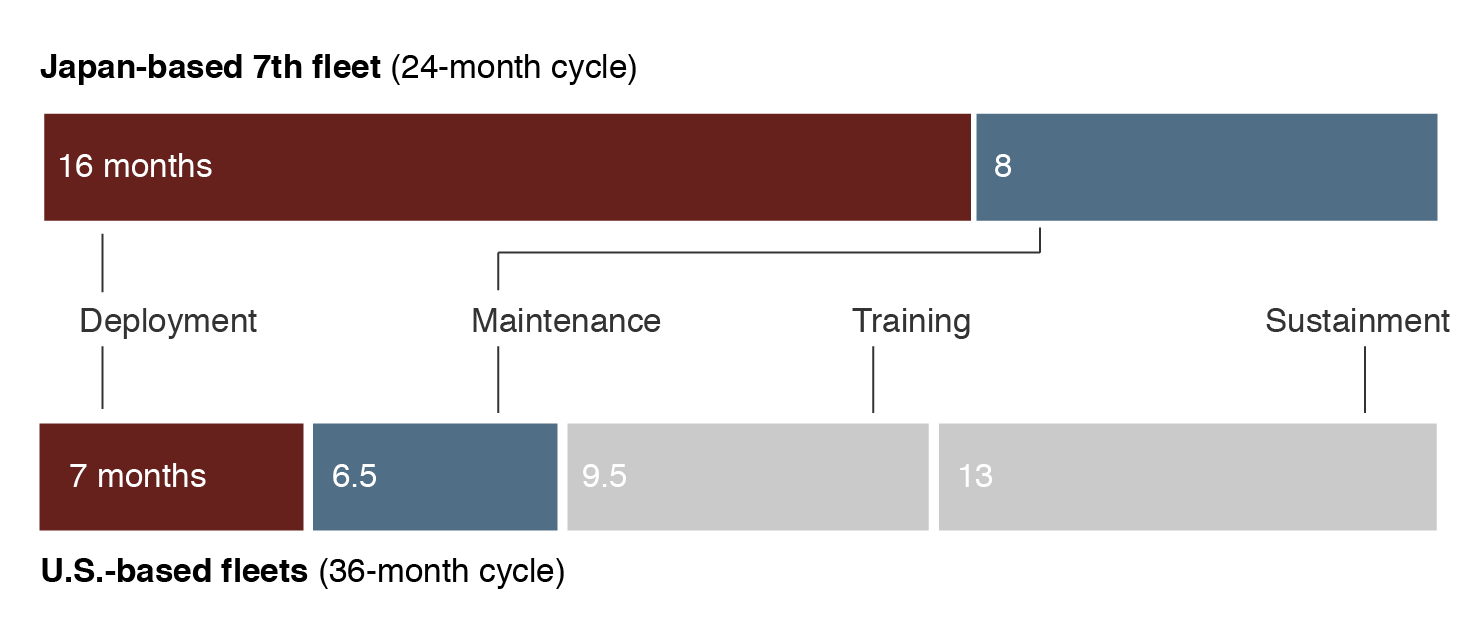

Seventh Fleet ships now will cycle through a 36-month operations period, with more time dedicated to maintenance and training time, a rotation closer to that of U.S. based ships.

Planned operational schedule for cruisers and destroyers homeported in Japan and the United States

Due to their permanent deployment status, ships homeported in Japan follow an operational schedule that limits dedicated training and maintenance periods. However, U.S. based ships follow the traditional fleet response plan cycle. Following the collisions of 2017, the 7th Fleet is transitioning to a schedule that resembles the U.S. cycle.

Source: GAO analysis of Navy data

The Navy also established the Naval Surface Group Western Pacific specifically to oversee readiness of Japan-based ships and ensure transparency of all related issues.

The struggle to accommodate increased mission demands is not exclusive to the 7th fleet. A 2015 report by the Government Accountability Office said the Navy met about 44 percent of combatant commanders’ requests and fulfilling them all “would require 150 more ships.”

According to Bryan Clark, former Special Assistant to the Chief of Naval Operations, the Navy has fulfilled roughly 50 percent of its requested missions for the past five years.

Bryan McGrath, a former destroyer commander now working as a national security consultant, said the U.S. simply does not have the Navy it needs to meet all that’s required of it.

“The insufficiently sized Navy that we have today, is not being funded and resourced sufficiently for what it’s being asked of,” he said.

Aboard the guided-missile cruiser Chancellorsville here in Yokosuka, Capt. D. Wilson Marks pointed out the crew – taking advantage of a recent dry dock period — has been recertified in skills requirements and is preparing to go back to sea.

The guided-missile cruiser USS Chancellorsville in dry dock for repairs and crew training at Fleet Activities Yokosuka in Yokosuka, Japan. (Edythe McNamee / Medill)

He said there has been a noted cultural shift as the Navy has taken steps to restore the 7th Fleet’s operational balance. He said he has more leeway to express concerns about readiness to complete mission tasks and to suggest alternative courses of action.

“I feel pretty confident that my operational commander who has told me this directly would listen,” he said.