The Navy plans to build dozens of new ships by 2023, but will need thousands more sailors to run them

By Matt Sussis and Yingjie Gu

WASHINGTON — The United States Navy plans to rapidly expand its fleet of ships, as part of the Trump era military buildup, but finding enough sailors to keep them operational could pose a serious challenge, according to analysts.

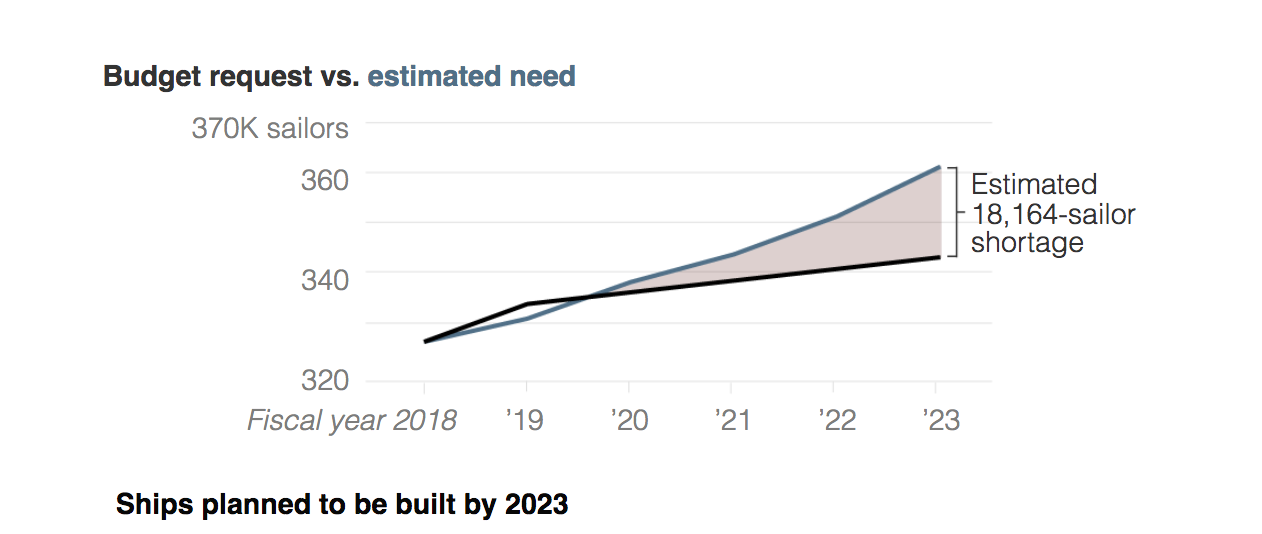

The Navy plans to reach 326 active ships by 2023 from its current 283, according to its long-range construction plan for fiscal year 2019. That net increase of 43 ships could require approximately 35,000 more sailors than the roughly 328,000 active duty sailors serving this year, based on Medill News Service/USA Today calculations. Ten ships are currently under construction.

Those calculations used the government’s ship construction and retirement schedules and were corroborated by multiple experts and military analysts.

However, the Navy is forecasting an increase in its total active personnel of only about half that number – 17,000 – by fiscal 2023. That would raise end strength – the total number of sailors in the Navy – to 344,800.

The Navy hasn’t operated at that level of manpower in more than a decade.

But some experts say that would still be inadequate to address the Navy’s long-term readiness needs and steadily growing mission requirements, and could exacerbate the problem of understaffing which likely contributed to the collisions of two destroyers last year.

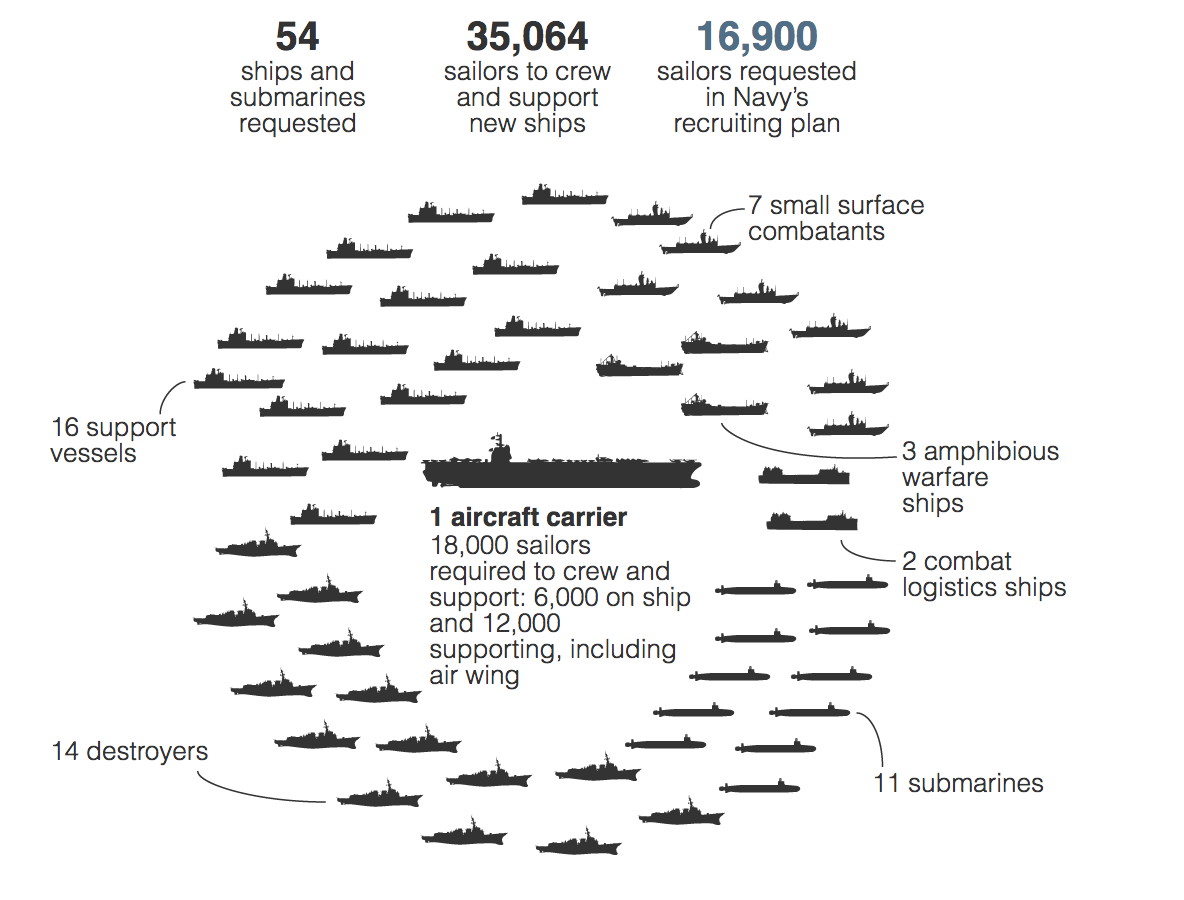

Overall, the Navy plans to build 54 new ships between fiscal 2019 and 2023, while decommissioning a number of others. Critics say Navy officials have either grossly underestimated their long-term operational costs to make their budget requests more palatable to the White House and Congress, or are convinced they can squeeze out operational savings once a future generation of ships is built and deployed.

But in the wake of last year’s fatal collisions involving the USS Fitzgerald and the USS John S. McCain that are being blamed on human error due to inadequate training, excessive work schedules and mission creep, underestimating future personnel needs is a high-risk maneuver.

“It looks like the Navy is falling back into its old bad habits in thinking it can do more with less,” said Todd Harrison, a defense budget analyst with the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a prominent military think tank. “They say, ‘Maybe we don’t need to fully man our ships. We can have people assigned to the frontline longer and keep fewer in the back office.’”

“There’s all these assumptions they can make to convince themselves they can do the job of 35,000 people with 17,000,” Harrison said.

The Navy said that its end strength plans properly align with its shipbuilding plans, and that its planned increase of 17,000 new sailors will be enough.

In a written response, the office of the Chief of Naval Personnel said that it was “cognizant of the challenges” of finding enough sailors for its growing fleet, but that it was confident it would be up for the task.

Yet in the past, the Navy has not always correctly matched its personnel numbers to its ship numbers, said Bradley Martin, a retired Navy captain and senior policy researcher at RAND Corporation, a defense think tank.

The Navy traditionally wants the ships first and hopes the sailors will follow, according to Martin and others.

“I think it’s not exactly a case of low-balling as much as it is not requesting the personnel increase until other parts of the plan are approved first,” he said in an interview. “Rather than try to program a particular force, the Navy keeps that number lower and then figures they’ll adjust for it later.”

But Martin warned that this strategy could pose recruiting challenges for the Navy down the road as they try to reach the higher number of personnel required.

“I will be frank: The Navy has often missed the mark of estimating what is actually needed in terms of people, which leads to painful adjustments,” he said.

Vice Adm. Robert P. Burke, chief of naval personnel, acknowledged during testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee on Feb. 14 that while recruiting and retention “are generally healthy,” competition for talent is steadily increasing. This is particularly true in recruiting and keeping technically skilled labor.

“The improving economy is beginning to impact recruiting and retention,” he said in prepared remarks. “We are in strong competition with the civilian sector and the other military services for the same talent pool.”

Burke added that following three consecutive years of declining end strength, “…we will achieve growth through a balanced approach of maximizing retention, increasing accessions, and ensuring the right Sailor, with the right skills and experience, is in the right place.”

The Navy has also increased reenlistment bonuses in an attempt to retain sailors. In February, it increased bonuses for 39 skills across 24 ratings to $30,000 for the lower ratings and as high as $100,000 for some SEALs, according to Navy Personnel Command.

New Ships

Personnel needs will be driven by the net increase of 43 ships by 2023, particularly by the addition of 14 Arleigh Burke-class destroyers, one new aircraft carrier, six new frigates, and three amphibious warfare ships, according to the Navy’s long-term construction plan. Destroyers have approximately 330 sailors per ship, aircraft carriers hold as many as 6,000, and the frigates hold approximately 205.

Just as the U.S. is ambitiously working to build up its fleet, so too are China and Russia.

Russia currently has 306 active-duty ships, while China has approximately 500 – including a massive fleet of nearly 300 small surface combatants. Both have plans to expand their smaller ships and undersea warfare capabilities.

The USS McCampbell, USS Benfold and USS Curtis Wilbur are Arleigh Burke-class destroyers, part of the U.S. 7th Fleet based at Commander Fleet Activities Yokosuka in Yokosuka, Japan. (Edythe McNamee / Medill)

China has become increasingly aggressive in a bid to dominate sea lanes in the Pacific Ocean and grow influence around the world. To that end, China has built and is sea testing its second aircraft carrier as it also develops its submarine and small surface combatant fleets. Those fleets include at least 12 corvettes (small warships) and ten submarines–including four attack submarines and six ballistic missile submarines.

Russia has become increasingly provocative in the South China Sea where it has agreed to cooperate militarily with Vietnam. It has plans to develop 16 additional guided missile corvettes, and is modernizing with advanced weapons systems more than a dozen of its attack submarines. However, the Russian Navy has had its share of technical problems related to its industrial base.

“The Russians are very good at coming up with unique ideas, but they’ve struggled to manufacture the hardware to actually carry it out,” said Washington-based naval analyst Christopher P. Cavas.

If the United States fulfills its shipbuilding plans by 2023, it will remain the most dominant sea force — particularly with respect to larger surface combatants and submarines, experts said.

But having the most powerful ships in the world has its limitations if there are not enough sailors to man those ships. The Navy will need to seriously improve its recruiting efforts beyond just small incentives such as pay raises and longer sabbaticals, said James R. Holmes, professor of strategy at the Naval War College.

“What we need to do is figure out how to fire youngsters’ passion and loyalty to the service, and that will involve more than offering tasty carrots,” he said. “It means crafting a patriotic appeal to join the Navy and take part in the grand undertaking that is strategic competition with Russia and China.”

While the Navy says it remains confident it can meet its goals, the Pentagon no longer routinely releases its recruiting statistics, making it difficult to discern how much progress has been made.