High-stakes brinksmanship in the Pacific

China and the U.S. flex muscles for regional dominance

By Casey Egan and Ricky Zipp

WASHINGTON — Chinese President Xi Jinping, dressed in dark green camouflage, stood on the deck of a destroyer earlier this year and admired the massive display of military might: 10,000 soldiers, sailors and other personnel, 76 fighter jets, and 48 warships.

It was China’s largest military exercise in the nation’s modern history. It was as if, on that April day, Beijing owned the South China Sea. And, analysts say, that was the point.

China has been rapidly militarizing disputed territories in the South China Sea, some say as part of a strategy to usurp U.S. geopolitical dominance of the region, including the critical shipping routes.

“The task of building a powerful People’s Navy has never been as urgent as it is today,” Xi proudly told service members after the historic exercise.

The U.S. has countered China’s island militarization with a more direct and aggressive approach.

After withdrawing an invitation to China to take part in an international military exercise in May, the U.S. also flew two B-52 bombers over a contested island in the South China Sea. This move—which the U.S. defended as a “routine flying mission”—was harshly criticized by China, adding to the provocative, back-and-forth between the two powers.

“There is a polarization going on in the region that’s fundamentally driven by this U.S.-China competition,” said Timothy Heath, a senior international defense researcher at the RAND Corporation, a prominent think tank. “All friction points are likely to see more friction.”

The Navy is also patrolling the sea lanes at a pace that has pushed its 7th Fleet operations tempo to the most demanding in decades in order to safeguard U.S. commercial interests and affirm the country’s commitments to regional allies and partners.

Last summer, after two 7th Fleet destroyers were involved in collisions that cost 17 sailors their lives, the intensity of Western Pacific operations was brought into broader public view.

U.S. military operations in the region were spotlighted even more in recent days, as President Trump held a June 12 summit in Singapore with North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un. And while Trump vowed to end U.S. war games with South Korean forces, the full impact on future U.S. Navy operations in the Western Pacific is far from clear, as are nearly all details coming out of their meeting.

Xi vowed during a 2015 speech at the White House that Beijing would not militarize outposts in the South China Sea. However, Xi also stated that China has the right to defend its “territorial sovereignty and lawful and legitimate maritime rights and interests” and said many of the islands have belonged to China since “ancient times.”

Bryan Clark, a former Navy officer and special assistant to the Chief of Naval Operations, said that China’s militarization of islands in the region has been incremental in order to avoid a dramatic escalation with the U.S or an outbreak of war. Yet, he said, the U.S. should have understood China’s strategy long ago and come up with an approach to resist it.

Over the last five years, China has methodically developed islands in the South China Sea that are in the middle of a territorial dispute with multiple other nations, ignoring international law and courts. The U.S. Navy has responded by routinely sailing warships through these disputed waters as a projection of military and political might.

In a 2015 speech in the White House Rose Garden, Chinese President Xi Jinping assured members of the press that his country would not militarize disputed outposts in the Spratly Island chain. (White House)

The U.S. also recently heightened tensions with China, by naming it as a direct competitor of the U.S. as part of the Trump administration’s release of its National Security Strategy (NSS) and National Defense Strategy, both of which were highly critical of Chinese aggression in the Indo-Pacific.

Robert Sutter, Professor of Practice of International Affairs at the Elliott School of George Washington University, said that the U.S. and China are in an “unremitting struggle,” and the language used by the Trump administration in the two national security reports has not been used by the U.S. in decades.

“China and Russia want to shape a world antithetical to U.S. values and interests,” stated the 2017 NSS. “China seeks to displace the United States in the Indo-Pacific region, expand the reaches of its state-driven economic model, and reorder the region in its favor.”

“We just haven’t seen something like this since Nixon,” Sutter said. “This is a Cold War document.”

The stakes of the Western Pacific chess match being played by the U.S. and China are potentially enormous.

“Everybody is keenly aware . . . [of] what’s at play and the importance that our interests are protected and understood,” said Capt. Michael Donnelly, commanding officer of the USS Ronald Reagan, in an interview in Yokosuka, Japan, homeport to the ship as the Navy’s forward deployed aircraft carrier.

The USS Ronald Reagan is the US Navy’s only forward deployed aircraft carrier. Its home port is Yokosuka, Japan home of the 7th Fleet. (Ricky Zipp / Medill)

The South China Sea is hotly contested for a litany of economic, political, and historical reasons. Twenty-one percent of all global trade made its way through the waterway in 2016, according to research by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). The same study found that nearly two-thirds of China’s maritime trade traversed the sea, and nearly 42 percent of Japan’s maritime trade did as well.

But the South China Sea has more than economic meaning for Indo-Pacific nations on its shores. In China’s case, the ties are also linked to nationalism and sovereignty claims.

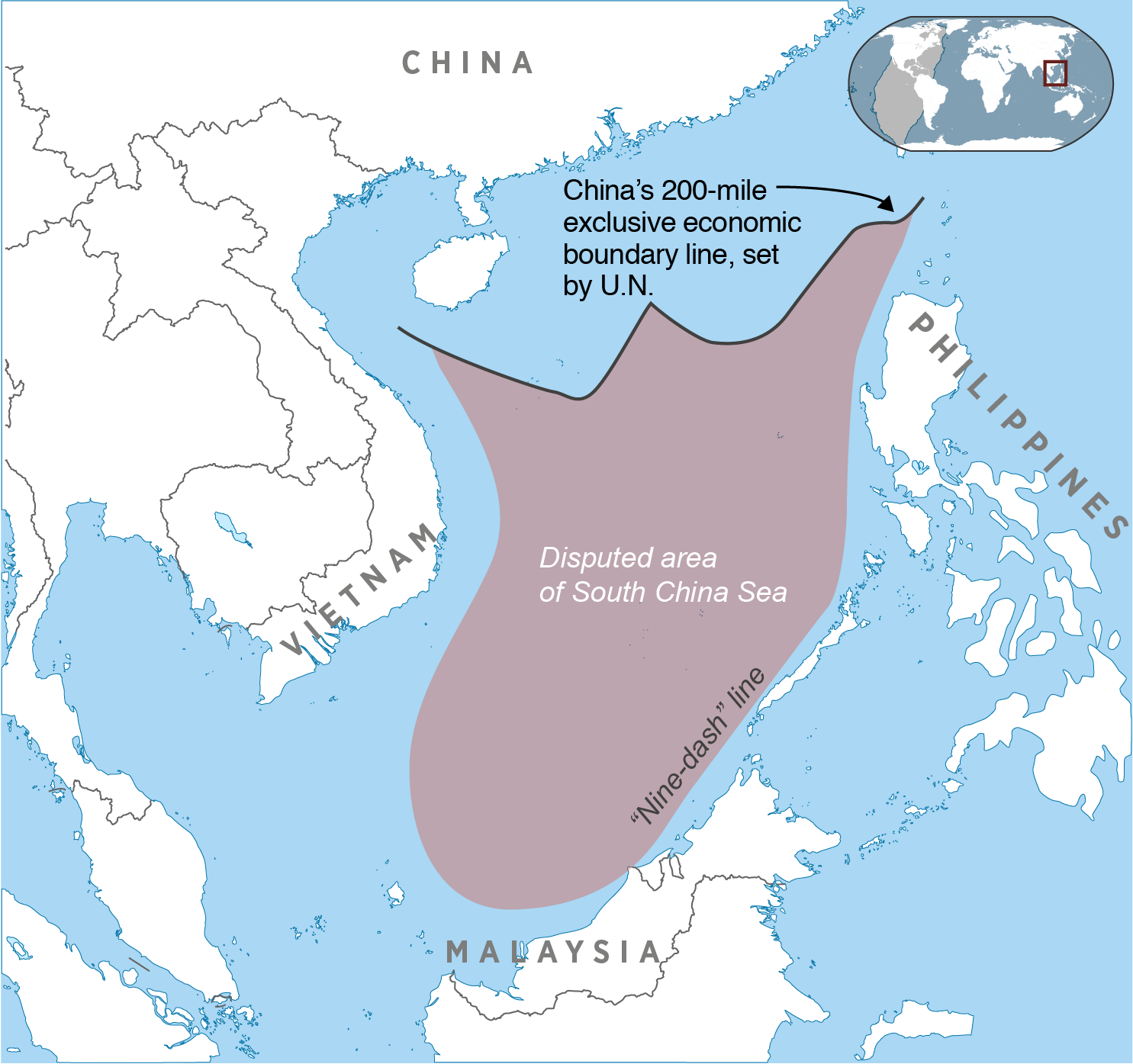

China believes it has territorial sovereignty over what is known as the “nine-dash line,” a region that encompasses the majority of the South China Sea and has been claimed as sovereign territory by the government of China since 1947.

While countries openly challenge their claim, China remains adamant that the area within the nine-dash line be recognized as its territory despite being disputed by the international community. China became more adamant after the discovery of oil and gas beneath the surface.

China’s disputed claim in the South China Sea

China’s sovereignty claim in the South China Sea includes the majority of the resource-rich waterway, a position of the country for over 70 years. A Hague-based international court ruled differently in 2016.

“From China’s perspective, there had been no dispute or contest until the 1970s when oil and gas were discovered in the region,” said Zhiqun Zhu, a professor of political science and international relations at Bucknell University and a member of the National Committee on United States-China Relations.

In March, China made a historic move by altering its constitution to remove term limits for presidents. That allows Xi to remain president for life. Xi has signaled a new era of Chinese power projection amidst unprecedented economic growth. Some analysts predict that China will surpass the U.S. as the largest economy in the world before 2030.

“Xi is undoubtedly the most powerful and most daring Chinese leader in decades ,” said Zhu in an email. “However, I do not think he is adventurous or irrational. Outsiders may think China’s moves in the [South China Sea] are aggressive, but Xi is unlikely to rock the boat and initiate a conflict in the region.”

In congressional testimony in March, Admiral Harry Harris, then the top military commander in the Pacific region, predicted that if Chinese military modernization continues at its current pace, the Chinese Navy will surpass Russia as the world’s second largest naval force by 2020.

There are two main island groups in the South China Sea that are at the center of the dispute: the Paracel islands and the Spratly islands, the same island group Xi vowed not to militarize.

However, China has now developed military facilities on seven of the islands in the group over the last few years. The islands have been outfitted with airstrips capable of landing and launching military aircraft, hangars that can hold fighter jets and bombers, barracks, and ammunition storage facilities.

Harris said that current features placed on the island are “short-term defensive,” but the U.S. should expect Beijing to use these facilities “to support advanced military capabilities.” Harris believes that these islands are meant to project China’s power across the entirety of the South China Sea.

Chinese development in the South China Sea

Satellite images show the before and after of Chinese development of military outposts on disputed islands and atolls in the South China Sea. Some of the islands are outfitted with military barracks, airplane hangars, and have 10,000 foot runways.

WOODY ISLAND This small island in the Paracel Island group has been rapidly developed over the course of the past five years. In May, China landed a long-range nuclear bomber on Woody Island, the first time it is believed to have done so in the South China Sea.

MISCHIEF REEF In March 2018, the USS Mustin, a guided missile destroyer, sailed within 12 nautical miles of Mischief Reef during a freedom of navigation operation to challenge China’s territorial claim.

SUBI REEF This outpost is located in the Spratly Islands and China assumed possession over the reef since 1988.

To challenge China’s claims and militarization over disputed island groups, the U.S. Navy regularly conducts freedom-of-navigation operations (FONOPs) through the South China Sea. FONOPs, in this case, involve the sailing of a naval vessel through the disputed waters to show that the U.S. does not recognize China’s nine-dash line claim.

Bonnie Glaser, director of the China Power project at CSIS, believes that the Trump administration is handling FONOPs differently than the Obama administration, calling the strategy “clearer, more regular, and directly challenging China in ways that the Obama administration was a little anxious about doing.”

Retired Admiral Gary Roughead, former Chief of Naval Operations who spent the majority of his career working the Indo-Pacific, said that the U.S. would need to be bolder if it wants to show a commitment to discouraging Chinese aggression.

“If you want to deter, you have to deter with something more than a freedom of navigation operation,” Roughead said in an interview.

Roughead believes a multi-pronged approach in the region would best signal U.S. resolve.

“We should operate more routinely in the South and East China Seas, with partners and also unilaterally,” he said in an email. “Associated with those exercises should be more frequent port calls in SE Asian ports with professional and humanitarian activities scheduled with respective host nation militaries and other organizations.”

China’s nine-dash line claim of territory was directly challenged by an international court in 2016, but this ruling has been ignored by China — which continues to justify its actions with their claim of historical rights to the area.

Neighboring countries also play an important role in both the U.S. and China’s pursuit for influence.

Vietnam and the Philippines, among a handful of countries, have growing economies that depend on the resources in the South China Sea. A crucial part of their economies depends on their ability to drill for oil and fish in nearby waters.

After Vietnam contracted a Spanish oil company to drill for oil in waters they believed to be within their sovereign territory, executives from Repsol, a Spanish oil firm, reportedly said that China threatened a military conflict with Vietnam in the Spratly islands if Vietnam went ahead with the project. Vietnam pulled out of the project in March.

The U.S. is taking a more accommodating approach to Vietnam. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the U.S. has increased its annual trade with Vietnam by around $53 billion since 2000.

The Navy is also extending a diplomatic hand to the Vietnamese. In March, the USS Carl Vinson made a port visit to Danang. That was the first visit to the country by a U.S. aircraft carrier since the end of the Vietnam War.

Heath, the RAND researcher, said that while the chance for a military conflict between the U.S. and China remains low, he believes that neither country is going to make significant strategic concessions regarding the South China Sea.

While the levels of tension between the U.S., China, and neighboring countries has fluctuated over the years, Heath says this new era of antagonism between the two powers is here to stay. “The trend is for this to start to become the new normal,” he said.

U.S. Navy personnel aboard the USS Carl Vinson interact with Vietnamese officials during the ship’s visit to the country in March 2018. The visit also acted as a form of diplomacy, as sailors engaged in a range of community service and relationship building exercises during their visit. (Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Nicholas Foley / U.S. Navy)