Story by Medill National Security Reporting Project

Produced by Jin Wu

ATLANTA – Six years ago, a senior U.S. public health official brought a map of the world to Capitol Hill to underscore what he said were gaping holes in the system designed to detect and contain infectious disease outbreaks before they could kill thousands or potentially even millions of people.

At the time, Dr. Scott Dowell was leading the much-touted Global Disease Detection Program here at the headquarters of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. Congress had established the GDD program six years before that to “protect the health of Americans and the global community by developing and strengthening public health capacity to rapidly detect and respond to emerging infectious diseases and bioterrorist threats.”

The centerpiece of GDD was supposed to be 18 regional health centers that the U.S. would establish in developing nations where endemic diseases like cholera and malaria had long been rampant, and in emerging hotspots where new and potentially catastrophic viruses were spawning.

These centers would establish labs and bio-surveillance capability and conduct training in cooperation with host country health agencies. And they would allow U.S. and World Health Organization officials to create an interconnected network that would rapidly detect and respond to isolated incidents of disease before they could turn into full-fledged outbreaks like the deadly Severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, that had caused a global panic back in 2003.

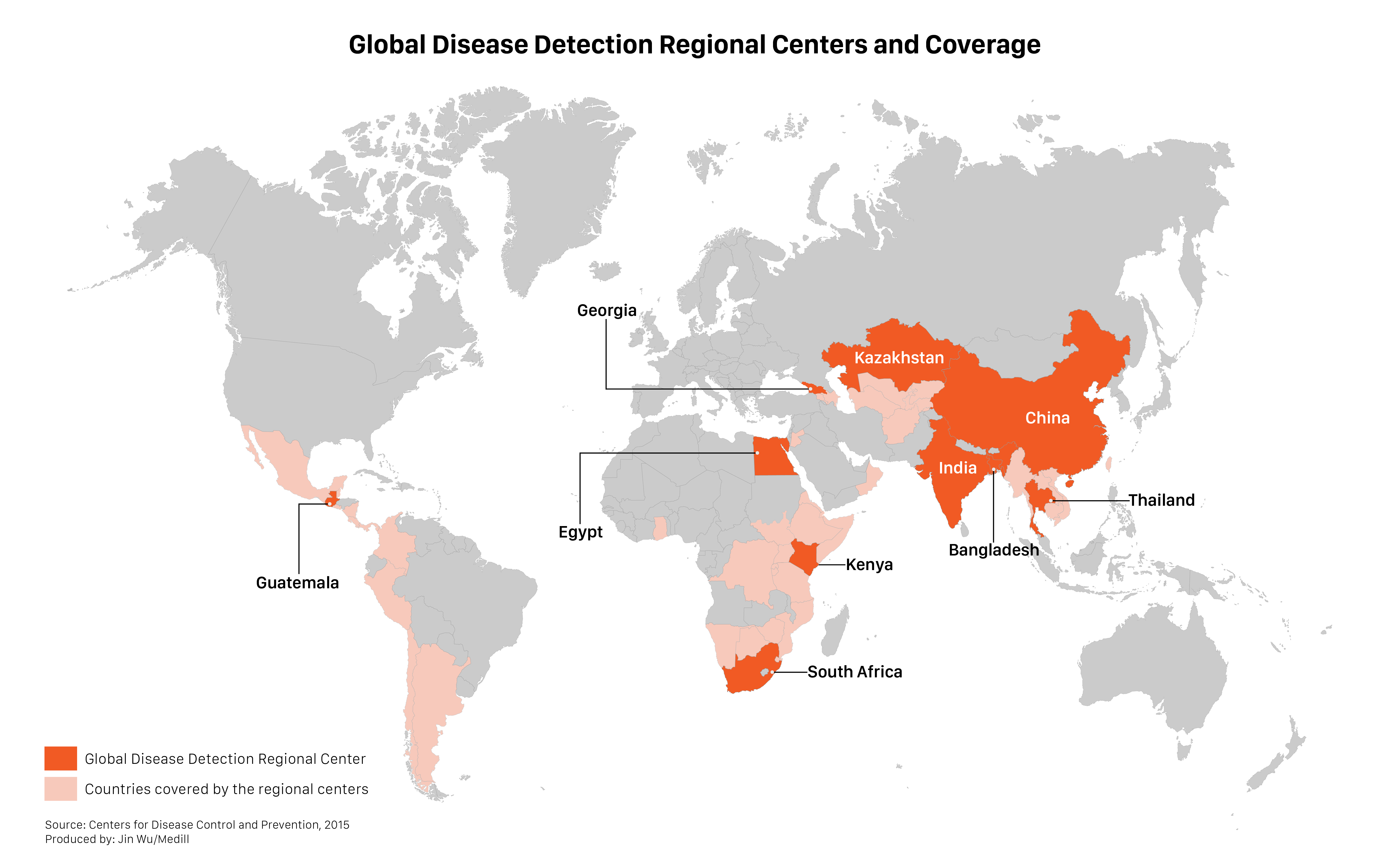

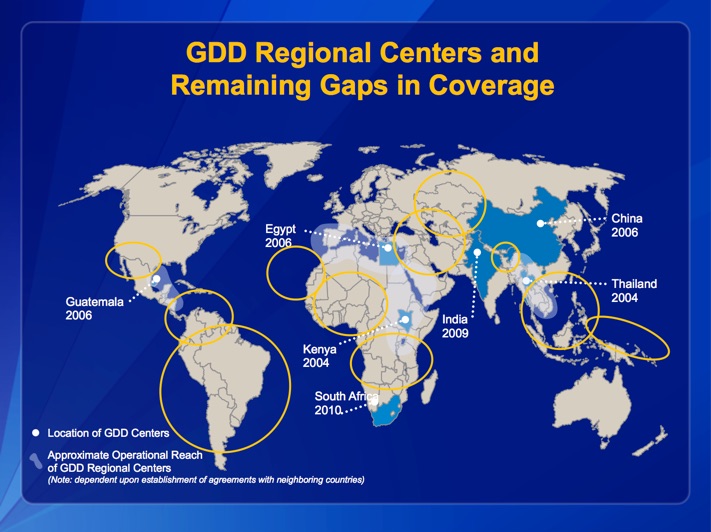

But by the time of Dowell’s visit, only seven of the 18 centers had been built, and at least some of them weren’t fully functional. And as Dowell’s annotated map showed, none of them covered some of the world’s most high-risk areas, including West and Central Africa, all of Latin America and other wide swaths of the developing world.

Dowell made the trip from Atlanta, as he did frequently, to explain the need for more U.S. funding to build the additional GDD centers, and to fulfill other mandates of the program. His trip had taken on added urgency after a devastating series of deadly infectious disease outbreaks in the years after SARS, including several involving an especially lethal virus – Ebola – in Africa from 2007 to 2009.

“That was the crux of much of our discussions with Congress in those years,” recalls Dowell, an accomplished epidemiologist who left the CDC in 2014 to lead public health surveillance initiatives for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. “We always showed West Africa as a gap in a place where there were epidemic threats but little capacity to respond. Pathogens tend to find those gaps, whether we recognize them or not.”

Dowell wasn’t the only one sounding the alarm.

In a July 2010 report by the U.S. Institute of Peace, an independent, bipartisan research institution funded by Congress, William J. Long also warned that the U.S. government’s lack of attention to the growing prevalence of infectious viral diseases had contributed to a true global security threat.

Dr. Scott Dowell, former director of Division of Global Disease Detection and Emergency Response

"We always showed West Africa as a gap in a place where there were epidemic threats but little capacity to respond."

He singled out the lack of funding for GDD, saying “that network is not in place, and only six centers are completed.”

“The U.S. government should not wait until after an infectious disease disaster before filling in the gaps in this system,” Long wrote.

Four years later, Long’s warnings came true. A new variation of the Ebola virus roared through three countries in West Africa, killing more than 11,000 people in one of the worst pandemics in recent history. The cost of the U.S. part of the response alone has been in the billions of dollars.

But the CDC never did build one of the 18 Global Disease Detection centers in West Africa.

U.S. officials now concede that if they had, the outbreak might have been stopped outright, or certainly contained before so many people were killed.

William J. Long, chair at the Sam Nunn School of International Affairs at the Georgia Institute of Technology

"The U.S. government should not wait until after an infectious disease disaster before filling in the gaps in this system."

“It’s a question I ask myself; if we had a GDD center there, if we had active surveillance, could we have picked up Ebola earlier? And I think you’d had to have your head buried in the sand to say no,” said Dr. Joel Montgomery, who oversees GDD as the chief of the Epidemiology, Informatics, and Surveillance Lab Branch in CDC’s Division of Global Health Protection. “Of course we would have picked it up earlier.”

“There has always been a plan to have 18 centers and one of them would be in West Africa,” Montgomery added. “I don’t think it was ever proposed and rejected. It just never went forward because of [a lack of] resources.”

The lack of a regional center in West Africa is emblematic of bigger structural problems at GDD that have compromised the effectiveness of the CDC’s principal program for identifying and containing infectious diseases around the world over the past 12 years, according to documents and more than two dozen current and former CDC officials and other experts interviewed for this story by Medill.

As of today, significant gaps in the network remain; only 10 of the promised facilities have been built and at least some are still not fully functional. All of South and Central America, for instance, are still covered by one center in Guatemala, despite a broad array of infectious diseases that affect millions of people in the region.

Dr. Joel Montgomery, Global Disease Detection director

"It’s a question I ask myself; if we had a GDD center there, if we had active surveillance, could we have picked up Ebola earlier? And I think you’d had to have your head buried in the sand to say no. Of course we would have picked it up earlier."

On January 15, the CDC issued an unprecedented travel warning cautioning pregnant women and women planning to become pregnant to postpone travel to a set of Latin American and Caribbean countries and territories experiencing outbreaks of a mosquito-spread disease known as Zika virus. CDC officials said they were concerned that the Zika virus was responsible for skyrocketing numbers of severe birth defects in Brazil.

Also, the program has had little in the way of oversight; there have been no specific audits or reviews of the overall GDD program despite at least $338 million being spent on it since 2004. CDC spokesperson Donda Hansen said other oversight efforts are used, including site visits by CDC technical experts and a requirement that most individual GDD overseas grantees, those who receive $300,000 or more, conduct annual independent audits.

And perhaps most importantly, the GDD program has never received close to the amount of funding it needed to function effectively, according to these records and officials.

From the GDD’s creation, Dowell and other key officials concluded it would take $200 million a year to run the kind of fully functioning public health early warning system that they envisioned. But since 2004, the program has usually received about one-sixth of that – an average of about $35 million a year – in part because senior U.S. health officials never asked for more.

An Urgent Need

Those U.S. public health officials have long argued that an interconnected global disease detection network was urgently needed.

In 1996, President Clinton established a national policy that called for a system almost identical to GDD, which would “establish a global infectious disease surveillance and response system, based on regional hubs and linked by modern communications.”

And in 2001, the Government Accountability Office, an independent, non-partisan federal watchdog agency, cited the need for a similar network of regional health centers to improve overseas laboratory capacity, disease surveillance and prevention of the spread of diseases in developing countries.

Two years later, SARS hit 27 countries in Asia, Europe and North and South America. The particularly virulent infectious disease, which spread when an infected person coughed or sneezed, ultimately infected 8,098 people, killed 774 of them and caused $30 billion in economic damage.

SARS prompted U.S. health officials to intensify their calls for an effective global disease detection program, and the GDD program was born. At the time, CDC’s numerous international programs were “somewhat siloed,” and the lack of coordination hampered detection and response efforts, senior CDC official Dr. Rohit Chitale said.

At CDC’s urging, Congress spent $11.6 million in fiscal year 2004 to establish GDD. Three centers would be built in each of the World Health Organization’s six regions, to bolster compliance with international health regulations requiring all countries to build core capacities for epidemic detection, reporting and response.

And the centers would link up with a GDD Operations Center, an analytical clearinghouse and coordination point at headquarters.

Thailand was chosen as one of the first centers, along with Kenya, in part because of a promising pilot project there that was run by Dowell, the International Emerging Infections Program. Dowell moved to Atlanta to launch GDD, using the Bangkok project as a model.

Other centers would be established in Guatemala, China and Egypt in 2006, Kazakhstan in 2008, India in 2009, South Africa in 2010, Bangladesh in 2011 and Georgia in 2013.

But from the beginning, there were concerns that a lack of adequate funding made it impossible for GDD officials to create the public health safety net that they – and Congress – wanted.

Starving for Support

Beginning in late 2007, the Ebola virus struck eastern and central Africa, killing about 40 people in Uganda and almost 200 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Other serious outbreaks occurred during the next few years, and in the run-up to the fiscal 2011 budget deliberations, Dowell returned to the Hill. He was armed with a PowerPoint presentation that touted GDD’s many successes, including responding to Ebola, all types of contagious influenzas, cholera and even the plague.

But his presentation, obtained by Medill, also included a map titled, “GDD Regional Centers and Remaining Gaps in Coverage,” showing all of the places that remained uncovered.

“Part of our consistent message was that there’s an interest in getting more GDD centers in critical parts of the world,” especially to close those gaps, Dowell said.

Dowell said that as a CDC official, his job was to educate Congress, not lobby for money. But public health advocates were clamoring for additional funding as well.

The Trust for America’s Health, a non-partisan, non-profit organization with many former U.S. health officials on its staff, issued a report each year calling for more significantly more funding for GDD. Its budget memos often included a map strikingly similar to Dowell’s, showing huge gaps in the coverage, and details about how the existing centers were not achieving the five basic core activities of outbreak response, surveillance, pathogen discovery, training and networking.

In his 2010 report, the U.S. Institute of Peace’s Long urged GDD funding at the full $200 million a year called for by Dowell and other GDD officials, noting that even that figure – a six-fold increase over its existing budget – was “still less than 2 percent of the U.S. global health budget.”

Long praised GDD officials for coming up with creative solutions to what he described as a “miniscule” budget, including leveraging donations from international organizations and private philanthropies.

But, he added, “While these governmental programs have been effective and entrepreneurial in augmenting their budgets, an ad hoc, opportunistic funding model does not allow for systematic planning and expansion of programs to meet a stated national priority.”

Each year, however, CDC and HHS requested a far lower figure from Congress, usually around the $35 average figure that was ultimately approved, according to documents and interviews.

Dowell and other GDD officials hoped for much more each year, but their annual funding requests were sharply reduced by more senior officials at CDC and HHS, and then again by Bush and Obama administration health and budget officials, who cited many competing budgetary priorities.

Fighting for funding

Adrienne Hallett, a senior staffer on the Senate Appropriations Committee, recalls Dowell making a compelling case year after year for why more GDD centers were needed in places like West Africa. But she said GDD was hurt by being forced to compete for scarce federal dollars with key domestic public health programs like the Head Start early childhood health and education initiative.

Hallett also said things got much worse for CDC – and the GDD program –when the Tea Party conservatives came into Congress and, later, due to sequestration. “They lost a lot of money… I mean, like $1 billion,” Hallett recalls of the overall CDC budget.

In 2011, budget reductions forced CDC to reduce functionality at its center in Kazakhstan, a hotbed of infectious diseases, to the point where “the center no longer serves as a GDD regional center,” according to a report that year by the Congressional Research Service. In a statement, CDC said, the Kazakhstan center was still “under development” in 2011.

But Congress is only partly to blame. Records and interviews show that CDC and HHS didn’t make GDD a priority even when they were flush with funding.

Funding for global health initiatives, in fact, increased five-fold during the Bush and Obama administrations, from $1.7 billion in fiscal year 2001 to $8.8 billion in fiscal 2010, according to the USIP report. Most of that money was directed to be spent on fighting high-profile individual diseases like AIDS and malaria, with just one percent allocated for programs like GDD that were designed to strengthen prevention-based international infectious disease surveillance and response efforts, the report said.

GDD senior official Leonard Peruski said it has always been difficult getting support for GDD because its focus is not on saving peoples’ lives but preventing them from getting sick in the first place. “It’s hard to sell,” he said. “It’s not something that’s easily quantifiable.”

One senior House Foreign Affairs staffer agreed. “We don’t do capacity building,” the staffer said. “We fund for emergencies.”

Even within GDD, there were differences of opinion about where to put the centers, and which locations were the highest priorities.

Several CDC officials said they used a complex risk-based assessment process to identify the locations with the most urgent need – like West Africa – but that they also required significant political and financial support from the host country in order to build up the local public health capacity. And that wasn’t easy to come by, especially in destabilized regions.

The placement of regional centers also hinged on existing partnerships between the U.S. and host countries.

“You can’t just plunk a Global Disease Detection Program anywhere,” said Hallett, who is now associate director for Legislative Policy and Analysis at the National Institutes of Health.

Success amid the Challenges

Despite its many financial challenges, the Global Disease Detection program has had its share of successes.

Between 2006 and 2014, the GDD program detected 77 new and potentially dangerous pathogens. It also responded to 1,735 outbreaks around the world, 748 of which saved lives and prevented the spread of disease. And the program provided short-term public health training for more than 97,000 participants and established 243 new diagnostic tests in 59 countries, CDC officials said in response to Medill questions.

“Those countries now have more trained epidemiologists, they have experience with detecting outbreaks and characterizing pathogens that they didn’t have before,” Dowell said. “So, it didn’t solve all the problems with the world’s epidemic response. But I think it made some important steps forward in clarifying what needed to be done.

At the Kenya GDD center, lab director Barry Fields worked with the University of Virginia to develop and deploy an innovative diagnostic test for various key diseases in 2010. The Taqman Array Card can screen many more patients, and much more quickly, for a wide variety of deadly pathogens. That has helped health officials quickly differentiate those with Ebola or highly contagious respiratory diseases from those who have less contagious illnesses that look similar, and quarantine those who are infected, Montgomery said.

Between 2006 and 2014, the GDD program detected 77 new and potentially dangerous pathogens. It also responded to 1,735 outbreaks around the world, 748 of which saved lives and prevented the spread of disease.

Fields also helped set up the first diagnostic laboratory in Liberia in 2014 at the height of the Ebola outbreak, delivering 700 pounds of equipment and testing 1,000 specimens in the first few weeks.

“It was scary,” he recalls. “They were building the hospital as we got there… At that time, you really couldn’t tell who was a patient and who was a worker at the hospital.”

The GDD center in Thailand has been instrumental in building capacity in Southeast Asia, and keeping an eye on emerging zoonotic diseases, or those that cross over from animals to humans. And the GDD’s one center for all of Central and South America is a case study in how officials have been forced to do to more with less.

The center, located on a university campus in Guatemala City, serves as the safety net to stop potentially dozens of diseases from spreading throughout the entire continent and elsewhere -- including entering the United States.

Peruski, the center director until last month, said he was especially concerned about mosquito-borne diseases like dengue fever, zika virus and chikungunya – known as arboviruses – that he says are mutating and “have rapidly blanketed the globe.”

Colombia alone has gone from zero cases to 500,000 just over the past year, he says. “And while they’re not as sexy or as dramatic as SARS, they are affecting a lot more people globally.”

But the Guatemala center has suffered significant budget cuts since 2010, forcing Peruski to slash by half its flagship Field Epidemiology Training Program. He also said he couldn’t fill key veterinarian, laboratory and administrative positions at the center, limiting its ability to cover the many countries it oversees.

“It just means there’s only so many people to go around; you can only keep people on the road so much to try to get things done,” Peruski said.

Despite those challenges, the Guatemala center has become a model for developing and exporting innovative and cost-effective public health programs that are now being used around the world, said GDD chief Montgomery.

An Uncertain Future

In the aftermath of the 2014 Ebola crisis, critics assailed the U.S. government and world health community for being unprepared to detect and contain the virus before it got out of hand. In interviews, current and former GDD officials said Ebola was just the kind of outbreak that GDD was established to prevent, in part through building up surveillance and detection capacity in host countries.

“If not, then why are we doing any of this?” Montgomery said, adding that such preventive response measures would have cost pennies on the dollar when compared to the billions spent on emergency response.

Now, the Obama administration is dedicating potentially billions of additional dollars for public health measures.

In February 2014, Obama joined the leaders of at least 40 countries in launching an ambitious new program called the Global Health Security Agenda.

The United States said it would pledge more than $1 billion in resources on the effort, much of it focusing on stopping future infectious disease outbreaks by strengthening health infrastructure and laboratory systems abroad and employing “an interconnected global network that can respond rapidly and effectively.”

More than half of the investment, according to a White House statement, will focus on Africa.

Meanwhile, in November 2015, the CDC announced that it would create a new Global Rapid Response Team to serve as a “deployable asset” to help the U.S. respond to public health outbreaks in key parts of Africa, the Middle East and Asia. The 50-person on-call staff, based at CDC headquarters, is supposed to offer assistance with activities such as capacity building, epidemiology and surveillance.

Privately, some GDD officials expressed concern that the GDD will have to compete with these new – and often similar – Obama administration-sponsored initiatives for funding and attention. They noted that the new Rapid Response initiative is not part of their program, and declined to comment on whether it was designed to plug holes in the GDD network.

Montgomery said he is optimistic that GDD will play a significant role in the U.S. government’s post-Ebola expansion of its global disease detection network.

In many ways, he said, the program laid the groundwork for the new Global Health Security Initiative, and its successes will help ensure that it stays funded – and relevant – for the rest of the Obama administration and well into the future, no matter which party takes the White House in the coming election.

But despite that new Obama administration emphasis on building public health surveillance capacity overseas, there are no plans to build the eight remaining centers to complete the GDD network promised back in 2004.

“It’s predicated on funding,” Montgomery said, “and I would say right now funding is limited.”

In November, Montgomery ran into Dowell, the GDD founder and former director, at a World Bank meeting in Senegal. He said the two discussed the program, and the challenges it faces.

“We agree; it’s not finished. West Africa, South America -- there are clearly areas where we don’t have visibility,” Montgomery said. That includes countries where Ebola recently struck. “We agree on that point; that we don’t have coverage.”

“It’s not finished,” Montgomery said of the GDD network. “That’s the bottom line.”