Story by Ezra Kaplan

Documentary by Aditya Prakash

Produced by Jin Wu

KARACHI, PAKISTAN –– Each month, polio vaccinators walk into neighborhoods across Karachi, winding their way through narrow alleyways in teams of two, always accompanied by at least one policeman armed with an automatic rifle. Nearby a paramilitary force lines the street, cordoning off the area.

Gulnaz Shirazi knows all too well why so much firepower is need. A polio vaccination supervisor, she sent her sister-in-law Fehmida and niece Madiha into the field three years ago to help administer the potentially life-saving drops to children, including those whose parents don’t want any part of the program because they believe it goes against their Muslim religion.

The two were gunned down in the streets by anti-vaccine zealots, adding to a grim toll -- over 100 Pakistanis associated with the polio vaccine campaign have been killed in the line of duty since the program first started in the 1990s.

Recently a Jan. 13 bomb attack outside a polio vaccine center in Quetta left 12 police officers and one soldier dead as vaccination teams prepared to head out on a campaign. It was the deadliest attack in the history of polio vaccination in Pakistan. In the fight to eradicate the world of the dreaded disease, the attacks have been a serious impediment to success.

Since 2012, nearly 100 Pakistanis associated with the polio vaccine campaign have been killed in the line of duty.

Sometimes when the vaccination campaign gets too stressful or dangerous and Shirazi thinks of quitting, she remembers her sister-in-law and the 18-year-old niece who wanted to go home early that day so that she could stop by the market to shop for dinner. “I like to feel as if I have Madiha to one side and Fehmida on the other and they are encouraging me,” she says. “It is as if their spirits tell me to keep fighting and not let their sacrifices go in vain.”

Shirazi is not the only one fighting. A small, slender woman of 34 who sports a leopard print burqa, she is part of a 100,000-strong army of polio workers, most of whom work only a few days per month and get compensated $5 per day. Despite their meager pay, they carry the label volunteer, perhaps because of the dangers they face on the job. Threats are constant and vaccination drives are often cancelled because authorities can’t drum up enough police and soldiers to protect them.

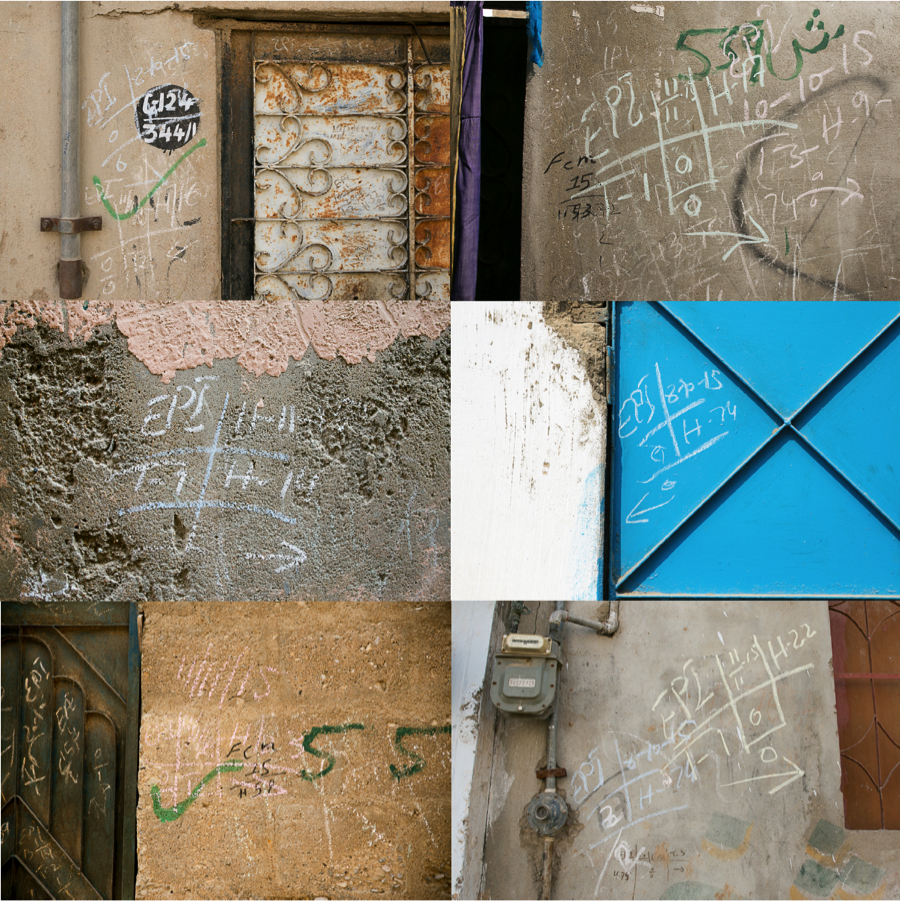

On one recent sunny day in this teeming port city, the vaccinators walk in pairs through the neighborhood of Sachal Goth, knocking on doors and asking if there are any children at home. Despite the sweltering heat, most of the women wear black burqas in keeping with local custom rooted in religious conservatism. They use chalk to mark the walls of the houses, leaving behind a half of a tic-tac-toe board with various numbers creating a record of their visit.

As they march through the dusty lanes, heads peer out of doors and curtains are drawn back from second floor windows as curious residents check out the scene. Nearby, the policemen stand nervously. With no body armor, no helmet, no side arm, no extra ammunition, they seem almost pathetic compared to the war-ready paramilitant Rangers lining the surrounding streets as a primary level of defense against extremists with intent to kill.

The vaccinators are each armed with a blue cold-storage box filled with vaccines, marked with a red sticker sporting the Rotary International symbol and block letters spelling out “END POLIO NOW,” and the belief that they are fighting for a noble cause.

“My reward is your child will be safe from the life of disability,” says Shirazi.

One father, dressed in the traditional white shalwar kameez, enthusiastically brings his daughter to the vaccinator. He pinches her mouth open while the health worker gives her two drops of the red liquid and marks her pinky with the same indelible ink that the country uses to mark the fingers of voters. She will need several more doses before she is vaccinated against the virus; it can take as many as 10 to 15 rounds. When vaccinators come back the next day, they will check the fingers of the kids so they can figure out who they missed.

Welcome to Pakistan’s polio war, where the victims are some of society’s most innocent, especially children.

Across the street, another vaccine worker confronts a mother who doesn’t want to give her children the drops. Other vaccinators and a community health worker congregate around the front door. They talk to the woman through the curtain-covered door, each presenting an argument for why her children need to be vaccinated. Eventually the woman acquiesces and opens the door holding her baby with another little girl running around her feet. Both kids get vaccinated.

One says yes, another says no. And so goes the rest of this vaccine drive.

This scene was played out across large swaths of Karachi during a monthly four-day polio drive last October, as part of the Islamic Republic’s resolute efforts to gain the upper hand over a disease that was once thought nearly eradicated, but that of late has made a roaring comeback.

Welcome to Pakistan’s polio war, where the victims are some of society’s most innocent, especially children.

The disease has no cure, is highly infectious, and can leave its childhood victims debilitated for life. Polio is a disease of paralysis, and in the rare case that the paralysis reaches the diaphragm, death comes in the form of suffocation.

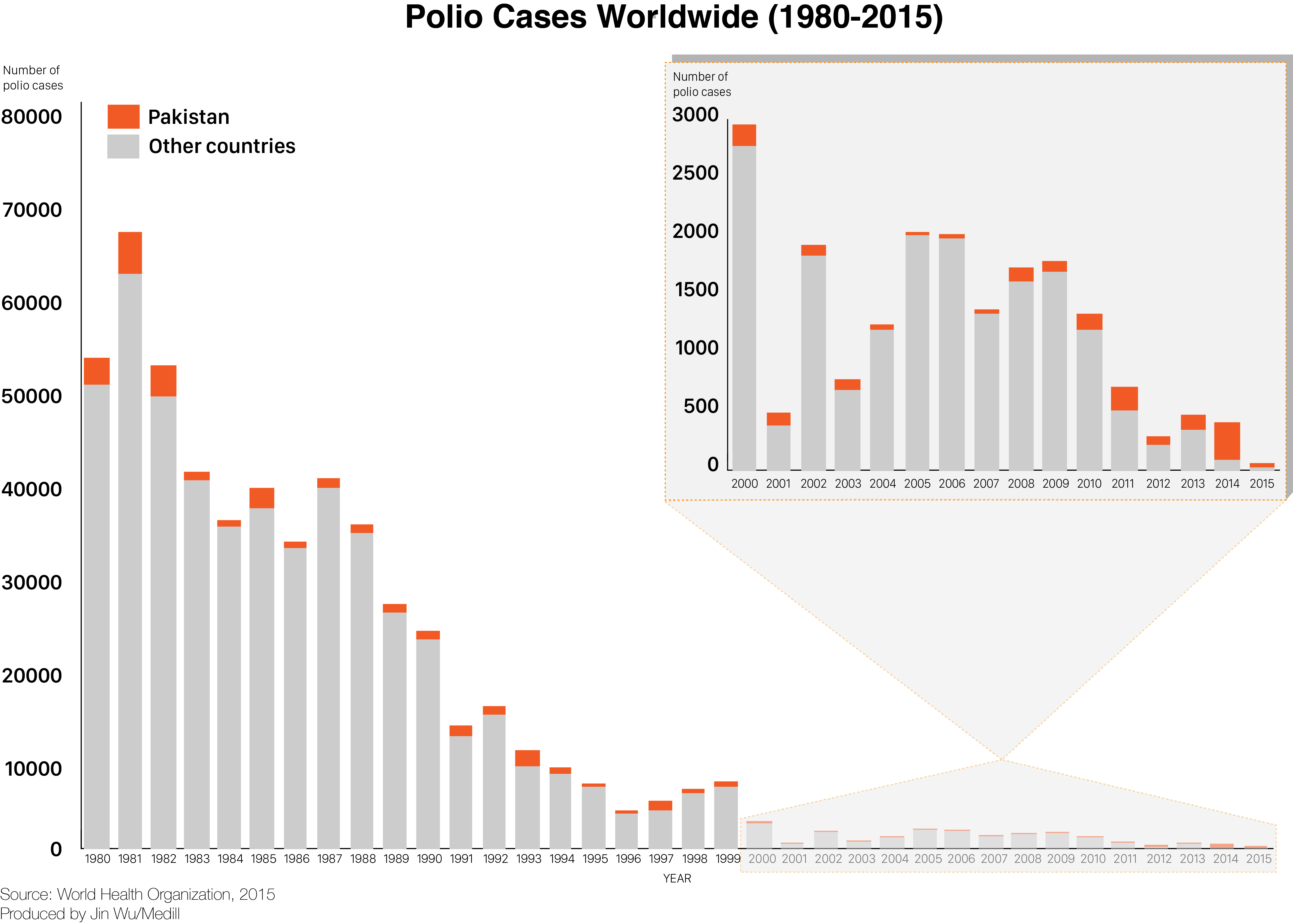

But there is a vaccine; it was invented 60 years ago. A simple two drops of red liquid in successive doses during early childhood is all it takes. And over the past 30 years, public health officials have spent more than $10 billion on a global campaign to eradicate polio through mass vaccinations. It has been hugely successful, with Nigeria becoming the latest country to declare itself polio-free this past September. But the last two countries where polio can still call home may prove to be the most difficult challenge to eradication: Pakistan and Afghanistan.

After years of progress, the two South Asian neighbors reversed course during an explosion of cases in 2014, prompting the World Health Organization to declare a public health emergency of international concern for only the second time ever. The first was in response to the outbreak of H1N1, Swine Flu.

A year later, in May 2015, WHO’s emergency committee issued another warning: “Despite the commendable progress, the implications of the continued risk of international spread from Pakistan and Afghanistan remain of concern.”

“This is a critical stage for global polio eradication during which the hard-earned gains can be quickly lost given fragility of progress and continued disruption of immunization systems in settings of conflict and complex humanitarian emergencies,” WHO said. “Countries affected by conflict are vulnerable to outbreaks of polio that can be difficult to detect and are very challenging and costly to control.”

The world almost got rid of polio, but now, it is finding out just how hard the virus is to eradicate.

World Health Organization emergency committee, 2015

"Despite the commendable progress, the implications of the continued risk of international spread from Pakistan and Afghanistan remain of concern."

Entering The Bloodstream

For most of the world polio is a disease of bygone years. Baby boomers in the US will remember the late summers in the 1950s being dubbed polio season as community pools shut down out of fear that children may catch the virus by swimming together. By the time the disease had been eliminated from the US in 1979, nearly 457,000 people had been diagnosed with some form of polio, according to Post-Polio Health International.

The main way to get polio is through person-to person contact. It enters the body through the mouth and spreads though contact with infected feces. For example, someone can get infected if they have feces (even if it is not visible) from an infected person on their hands and they touch their mouth. Once the virus enters the body, it takes up residence in the gut, where it reproduces, usually without symptoms. From there it enters the bloodstream, invades nervous system tissue and causes poliomyelitis.

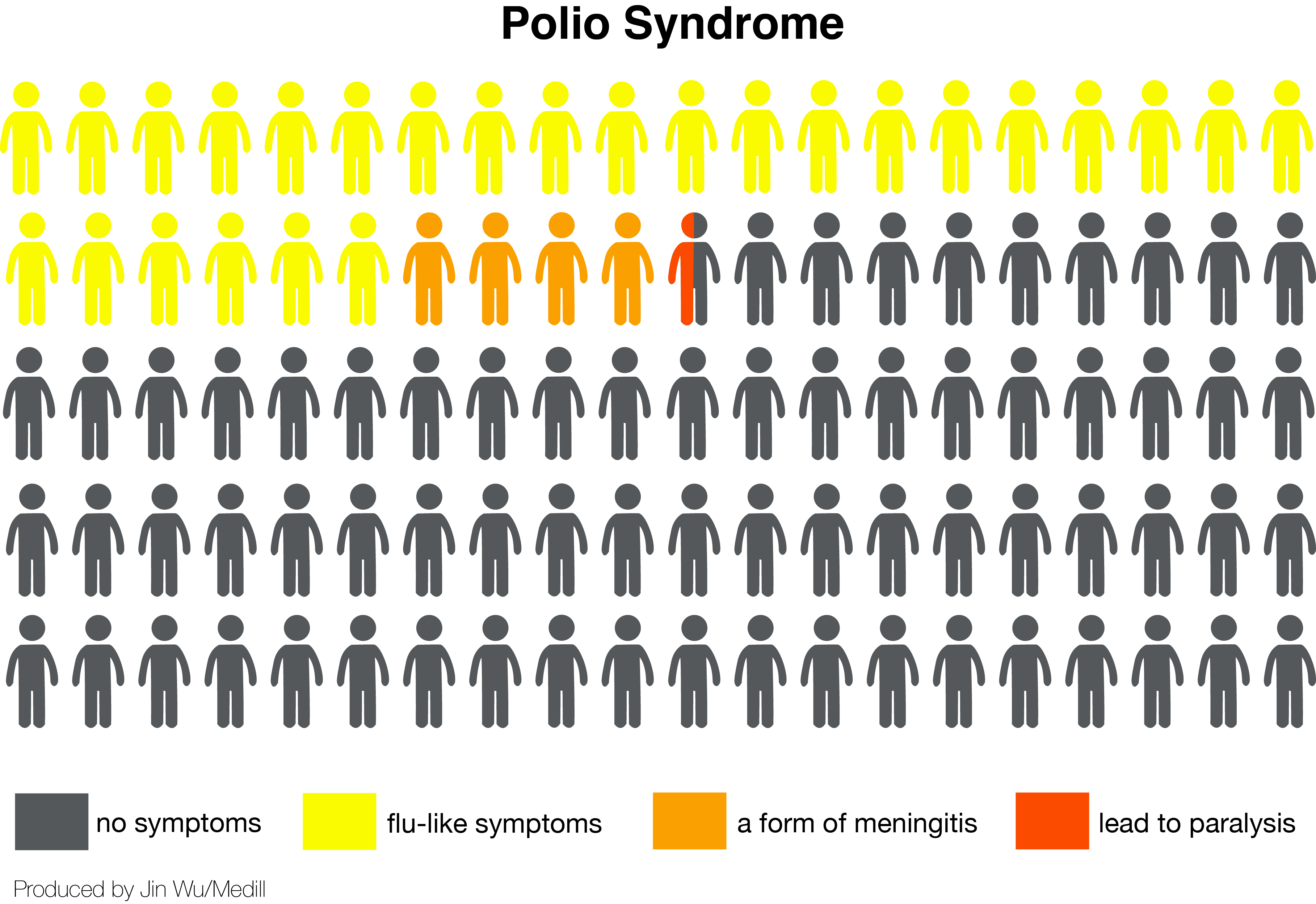

About 70 percent of people who get infected with poliovirus don’t have any symptoms; 25 percent have flu-like symptoms; 4 percent have a form of meningitis. Only about 1 in 200 polio infections lead to paralysis, which usually begins with weakness and ultimately loss of the use of their extremities, most often starting with a lower leg. Although victims may recover varying degrees of function, the damage is often irreversible.

Here’s the tricky thing about polio: even though only one of the 200 kids who got infected with the disease became paralyzed, the other 199 can be active carriers. For 1 to 2 weeks they are walking, talking–and traveling–polio factories.

To make matters worse, children who are malnourished with frequent bouts of diarrhea are even more susceptible to the virus because of a weakened immune system. It just so happens that many children in Pakistan and Afghanistan are both.

In theory, simply washing your hands and practicing good hygiene could interrupt the transmission of polio. But polio is a stubborn virus and hand washing is still making its way into the culture in the region. Still others must contend with contaminated water and food that make transmission of the virus hard to avoid.

In addition, some of the most vulnerable are two and three-year-olds, who are too young to practice good hygiene on their own.

“This is one of those diseases that, as much as you try to prevent transmission, you really do need a vaccine if you want to control polio,” said Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease in the US.

The vaccine is readily cheap, and plentiful. But the Pakistan government’s aggressive effort to use it has created an enormous amount of strife and, at times, turned urban Karachi neighborhoods into outright conflict zones.

The Politicization of Polio

On August 31, 2014, two-year-old Hazrat Bilal spiked a high fever after nearly a week of diarrhea. A day later, he was in the hospital, unable to stand, sit or even hold his own head up. He had been sick for over a month and the doctors were so concerned that they were getting ready to put him on a ventilator when the formal diagnosis came: polio.

A year and a half later, Bilal’s condition has improved, but during a recent visit, he squirmed and whined uncomfortably in his father’s lap, his right leg dangling limply.

“It’s in God’s hands now,” Khayal Muhammad, Bilal’s father, said of his son’s future. He told Medill that he hadn’t ever been vaccinated himself, nor did he plan on ever giving the vaccine to his other child, none of whom have polio – yet.

But Bilal didn’t have to get polio. His house had been repeatedly visited by vaccinator teams, according to WHO records. Each time they offered the vaccine. Each time, his family turned them away. According to the official WHO report obtained by Medill, Bilal never received a single a single dose of polio vaccine. The report explained that the family is a “silent refusal” meaning that the family has failed to vaccinate their children on multiple occasions. The report said that although polio teams were able to physically access the neighborhood, many families refused the vaccine.

When Medill presented this documentation to Muhammad, he stood by his story, that Bilal had been vaccinated but got the disease anyway. But that story has changed, as Muhammad has given conflicting reports as to how many vaccines Bilal had received.

The refusal families in Pakistan believe that the vaccine is a part of an effort by the west to control Muslims while also causing infertility in children.

Muhammad owns a roadside restaurant in a neighborhood that is dominated by the Pashtuns, an ethnicity that originates in the northwest part of Pakistan. The Pashtun people are known for both being transient/migratory and for being ideologically conservative and extreme. As a result the neighborhood has a polio vaccine refusal rate of 25 percent, making the neighborhood highly vulnerable to polio outbreaks.

These refusal families are representative of a small but not insignificant minority of those in Pakistan who believe that the vaccine is a part of an effort by the west to control Muslims while also causing infertility in children.

Bilal is too young to know that he is at the beginning of a life of hardship and deformity, constrained by wheelchairs, leg braces and the prejudice that is visited upon a disabled man in an unforgiving city -- and country -- that is far from accommodating.

Resistance to the Vaccine

Refusals are the number one impediment to eradication, says Shahnaz Wazir Ali, the former Prime Minister’s point person for the eradication of polio.

Throughout the history of the vaccine campaign, extremist Islamic scholars have periodically issued fatwas, or religious decrees, declaring the polio vaccine to be un-Islamic. To combat this, health workers carry a government published collection of fatwas from some of the most highly regarded Islamic scholars in support of the polio vaccine.

“In my view, the public in general is more ignorant than anti-vaccination,” Iqbal Memon, a Karachi based pediatrician who has been involved in the national response to polio since the 1990s, told Medill. “They just need to be educated.”

But what the residents really want is a sewage system, clean drinking water, and a reliable health clinic to take care of their family members when they fall ill. In fact, they demand it and it has become an ultimatum between parents and vaccinators.

Residents of have become frustrated by the constant visits from health workers when the government is failing to provide critical resources – many people in the province are forced to rely on contaminated groundwater for their drinking supply. They protest by refusing to vaccinate their children until they get the services they demand.

“People have no faith in the government,” said Memon. “The general population does not believe that the health workers of the government are so good and honest and sincere for the cause. It’s a lack of confidence.”

While the residents of Karachi are demanding more basic resources, the government is struggling to simply protect the vaccination workers.

“If we were running a program of immunization and protection through the two drops without any security threats, I think we would have done it two years ago,” Ali told Medill.

The vaccinator killings -- and refusals -- skyrocketed after it was revealed in 2012 that the Central Intelligence Agency used a sham hepatitis vaccination campaign in the hunt for Osama bin Laden. The CIA’s use of the vaccine campaign as cover for gathering intelligence did irreparable harm to the trust that had been built up between health workers and communities in Pakistan.

The following year, the Pakistani Taliban used polio vaccines as a political football as it pressured the US to cease the drone strikes that had become an almost daily affair. Their reasoning was straightforward: You can’t fund a vaccination campaign for a population while you are dropping bombs on those very same people.

Shahnaz Wazir Ali, formerly the Prime Minister’s Focal Person for Polio

"If we were running a program of immunization and protection through the two drops without any security threats, I think we would have done it two years ago."

The vaccination campaign nearly ground to a halt as it was no longer safe to send vaccinators into many of the areas most in need. Nearly 270,000 children were deprived of the polio vaccine, said Ali. It wasn’t until 2014 that the consequences of the vaccine ban became clear. That year there were 306 cases of polio in Pakistan alone, more than five times as many cases as before the ban.

Pakistan was going against the worldwide trend toward eradication. And polio was spreading.

Fighting through the Grief

Gulnaz Shirazi became a polio worker in 2011 the same year she and her husband divorced over her inability to have children. She gave up teaching the Quran to be a polio worker, believing it to be an even more noble cause and strenuously disagrees with those who argue that the vaccine goes against Islamic teachings. Five other women in Shirazi’s family also became polio workers, but she was the only one to be promoted to an area manager. It was that promotion that put her in a position to send her niece and sister-in-law out on the day they were killed more than three years ago.

She said Fehmida and Madiha were going door-to-door vaccinating children when two men drove up on motorbikes with their young cousin, who they said needed the vaccine.

As the two women got out a vaccine to give to the child, the men opened fire, killing both of them. Two other women were separately killed that day in three consecutive attacks in different areas of Karachi.

“It was the most painful time of my life,” she told Medill in an interview at her office at a Karachi hospital. “The time after those two bodies came to our house was unbearable.”

“My mother asked me to return to teaching Quran again, she said that too was noble work. She said we have seen the bodies go to the police station and a public hospital after being picked up from a strange place. What will I tell everyone if something happens to you?”

Her mother, and Shirazi herself, also worry about the crushing stress that comes with the job, especially now that she is a supervisor who focuses specifically on the most difficult refusal cases. Her job now is to change the minds of those who are most adamantly opposed to vaccinating their children.

“The hardest is when you have to keep your patience while trying to explain the importance of vaccinating a child to a refusing parent. You feel like hitting that person or falling down on your knees to beg him to make your job easier,” said Shirazi.

“Women polio workers take a huge risk, as do the male workers, but a woman polio worker more so,” explains Ali, the technical coordinator for the area. “She steps out of her home, she goes up and down alleyways, she climbs multiple stories in apartment buildings, she walks many miles from village to village. This is taking a woman out of her own home where normally a woman’s life is centered, and asking her to do something which is pretty non-traditional.”

The cultural norms of Pakistan create an environment where women are better situated to work as vaccinators since it involves going into strangers’ houses. As a result, women have been disproportionally victimized by the extremist attacks.

For Shirazi though, the work is an opportunity to develop an identity, beyond the traditional role as mother and wife.

“Women have a big role to play in the building of any society,” said Shirazi. “The times have changed. These are not the times when men can dictate women to just be their homemakers and care takers.”

The Battle to Eradicate Polio Begins

On the heels of the eradication of smallpox, the World Health Assembly set out in 1988 to eradicate polio once and for all. One of its first partners was Rotary International, an international service organization, that launched a successful fundraising campaign to jumpstart the eradication efforts. If successful, polio would be only the second disease to be eradicated outright.

It has taken $10 billion over the course of three decades to reduce the number of global polio cases by 99 percent. But according to the Council on Foreign Relations, it will take another $5.5 billion to eradicate the last one percent of polio.

Though polio has been relegated to only two countries, the disease has a bad habit of reappearing, often in conflict zones where access to clean water, safe food and proper hygiene isn’t always easy. In 2013, amidst the ongoing civil war and after 14 years being polio free, Syria saw an outbreak of the disease resulting in 36 children becoming paralyzed. When scientists mapped the genetic material of the virus, they found that it was most closely related to a strain from Pakistan. Somehow, Pakistani polio was getting kids in Syria sick.

Because so few polio cases show the traditional symptoms of paralysis, global health experts have to rely on more than just human surveillance to track the path of the spread of disease.

According to the Council on Foreign Relations, it will take another $5.5 billion to eradicate the last one percent of polio.

“Environmental surveillance can be helpful in determining if there is in fact polio out there even though there are no (paralytic) cases,” said Fauci. “For example if you test the sewage in a particular city or country and you get poliovirus out, you know that you have not yet eradicated polio. That means that someone, somewhere, even if that person is not sick, is excreting poliovirus in their feces and it’s getting into the sewer system.”

This process of testing sewage systems has shown the virus turning up in some unexpected places. In recent years, wild poliovirus turned up during environmental sampling in both Brazil and Israel, though no one got sick in either country. Their populations are regularly immunized, so the virus never found a host.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease

"When you have polio anywhere in the world, it is a risk to everywhere in the world."

The fact is, polio is a highly mobile, highly infectious virus that is really good at finding unvaccinated children.

“When you have polio anywhere in the world, it is a risk to everywhere in the world,” said Fauci. “The good thing about polio is that there is no natural animal host. So if you really do eliminate polio from the human population, it will stay eliminated.”

The War Room

“The war on polio is yet to be won. We are at the end and we are not truly losing but we are not truly winning,” said Memon who has been working with the Pakistani government and health sector from the beginning of eradication efforts.

Just this year, Nigeria beat the disease by centralizing its response. Health officials there created a war room, polio style.

It was called the Emergency Operations Center, and earlier this year, Pakistan created one of its own.

The Sindh provincial EOC is a neat three-story building fortified by double stacked sand-filled bastions, reminiscent of a forward operating base in Afghanistan but situated in the middle of Karachi. The high security on the outside is in stark contrast to the modern but drab interior. Conference rooms are mixed with offices and the walls are covered with maps of the province and city punctuated by pins representing where polio cases have been identified.

Polio eradication is a complicated undertaking with many moving parts and partner organizations. From UNICEF to the WHO to Rotary International, some sort of coordination is paramount.

“Previously UNICEF used to sit in its offices, WHO in its offices and so on and so forth. But now we are all under one roof and we are a seamless coordinated team,” said Ali who was part of the initial planning to create the EOCs when she worked as the prime minister’s focal person for polio.

There are both national and local EOCs. Each one is housed in a building funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Inside, community health organizers, security analysts, religious community liaisons and technical coordinators all work side-by-side under one roof.

Shahnaz Wazir Ali, formerly the Prime Minister’s Focal Person for Polio

"We had all hoped by 2015 we would be in a position to say that Pakistan had really reduced the number of cases. Now it’s shifted to 2016."

In the national EOC, in Islamabad, a control center is staffed 24 hours a day during the campaign and coordinators work with real time information about the thousands of vaccination teams in the field.

At the top, Nawaz Sharif, the prime minister of Pakistan, leads the task force raising the bar and the responsibility for success. But that may not be enough to get the job done. Experts agree: polio should have been gone years ago.

“The timeline has been a bit of a shifting goalpost,” said Ali. “We had all hoped by 2015 we would be in a position to say that Pakistan had really reduced the number of cases. Now it’s shifted to 2016.”

But the numbers are going the wrong way. In October and November of last year, the first two months of what is normally the low season for polio, six cases were reported in Karachi after an entire year being polio free.This year there has been a total of eight cases of polio confirmed in Pakistan.

“It’s extremely disturbing because we have been putting out an extraordinary effort to contain the virus,” said Ali “I think it’s still going to be difficult.”

Additional reporting by Tehmina Qureshi and Hamid ur Rehman in Karachi, Pakistan