To Feed or Not to Feed

FORT BRAGG, N.C. — When Typhoon Haiyan struck the Philippines last November, U.S. troops jumped into action to support the immediate response effort – including transporting and distributing emergency food aid.

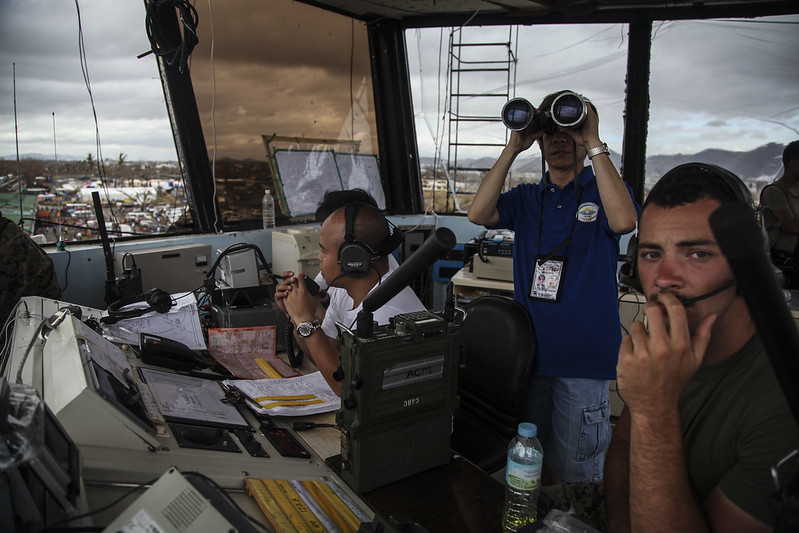

At its peak, Joint Task Force 505 included more than 13,400 personnel from various branches of the military, 66 aircraft and 12 naval vessels. It used the U.S. military’s massive resources to deliver food, shelter, medical kits and water to hard-hit but remote locations that would be otherwise unreachable.

U.S. troops logged 2,748 flight hours in 1,304 flights, transporting more than 2,000 relief workers into Tacloban City and airlifting 21,402 people from afflicted areas, according to Maj. Christian Devine of the U.S. Marine Corps, a public affairs officer for the U.S. Pacific Command (USPACOM) in Hawaii. During the first three weeks alone, the U.S. military delivered 2,495 tons of relief supplies and equipment.

(Courtesy of Department of Defense)

But by Dec. 1, less than a month after Haiyan’s landfall, most of the American troops were gone.

To a civilian bystander, such a hasty retreat might seem irrational. Why would the Pentagon mobilize all of those resources if it didn’t plan on staying longer?

The answer is simple: The U.S. government knows from experience how sensitive such military interventions in humanitarian crises can be, no matter how well-intentioned. And so, over time, a carefully choreographed arrangement has evolved between the U.S. Agency for International Development, the military and other key stakeholders so that there won’t be any surprises.

The relationship is a complicated evolving one, ruled by a complex set of military policies and doctrine, USAID rules and even United Nations guidelines.

“Feeding people is always involved in military humanitarian efforts. It’s a big part of it,” says Conrad Crane, a stability operations expert and the chief of historical services at the Army War College’s Heritage and Education Center. “It’s always something you plan for. And the idea is you always plan to hand it off to a civilian agency, and hopefully quicker rather than later.”

That’s what happened in the Philippines.

“We’re only going to be there as long as we are needed, but no longer than required,” Devine said.

Assistant USAID Administrator Nancy Lindborg said the response to Haiyan was a textbook example of a successful civilian-military partnership during a humanitarian crisis.

“The critical role is for the U.S. military is filling those incredibly urgent gaps that only their lift capacity can fill in the earliest days of a response,” Lindborg said.

Because USAID is the designated lead U.S. agency in such situations, its specially trained Disaster Assistance Response Teams worked hand in glove with the military to direct their coordinated response and to prioritize what goods – including emergency food aid – went on the air bridge to save as many lives as possible, Lindborg said.

The coordinated response to Haiyan was merely the latest in the history of the U.S. “civ-mil” cooperation in foreign-disaster assistance. In recent years, the two have drawn closer.

The two organizations have established a robust liaison capacity: two military representatives from U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) currently serve at USAID in Washington, D.C., and a USAID foreign service officer represents the agency as a senior development advisor at SOCOM’s Tampa, Fl. Headquarters.

USAID said it helps train hundreds of military personnel prior to Afghanistan stability-ops deployments and provides staff to teach courses at the Joint Special Operations University (JSOU). In turn, it said, SOCOM – among other things – lets USAID borrow technical experts “to help support USAID country and contingency planning.”

SOCOM’s Interagency Partnership Program – through which this collaboration occurs –is rooted in the U.S. global war on terror. A centerpiece of it: the Special Operations Support Teams, in which SOCOM personnel are deployed to both military and civilian agencies to work together on anti-terrorism planning. The collaboration was conceived in the aftermath of 9/11, and the first Inter-Agency Task Force was created at SOCOM headquarters in 2005.

Back in 2008, then-presidential candidate Barack Obama’s campaign platform included a proposal for “a 21st Century Military for America,” that beefed up the military’s role in aiding allies in humanitarian responses and winning “hearts and minds along the way.

And since he took office, U.S. troops has responded – including the 2010 Haitian earthquake, the 2010 Pakistan flooding, the 2011 Japanese earthquake and Haiyan.

A complicated relationship

American forces have come to the aid of people around the world since at least the 1800s, according to the Congressional Research Service, the independent research arm of Congress.

That includes flying food into postwar Europe during the Berlin Airlift of 1948-1949, providing food and emergency relief supplies to the victims of Hurricane Mitch in Honduras and El Salvador in 1998, the Turkish earthquake of 1999 and the 2004 Indonesian tsunami.

One key military deployment in recent years was the post-earthquake relief effort in Haiti in 2010. U.S. troops helped to establish logistical channels to distribute food, water and other aid.

Troops also played a key role in distributing humanitarian aid during the Iraq and Afghan wars, working with local government and military forces to facilitate the delivery of food and other types of aid (such as backpacks for children) to areas of need.

And since the 1980s, a handful of U.S. laws and regulations have given the military permission to get involved in humanitarian aid. They include: The ability to use Pentagon funds for humanitarian-related transport, to move select donated humanitarian goods on military ships and aircraft and to appropriate nonlethal surplus military supplies for humanitarian relief.

But not all humanitarian aid responses have gone smoothly for the military.

In December 1992, in response to a request from the United Nations, President George H.W. Bush ordered 25,000 U.S. troops into Somalia to lead a U.N. task force charged with creating enough stability that so food aid could be provided to its residents. Bush planned for this to be a short-term commitment, and his successor, President Bill Clinton, let the United Nations take the reins on May 4, 1993, reducing the U.S. military presence in the country.

Escalating tensions and violence between the Somali government and U.N. forces that followed eventually led to the deployment of U.S. troops to seek out Somali leader Gen. Mohammed Farah Aidid. The chain of events set in motion by this break from purely humanitarian involvement in the country eventually led to shooting down of two U.S. Black Hawk helicopters and the slaying of 18 U.S. soldiers in the event that has come to be known as Black Hawk Down.

A 2008 CRS report said that military involvement in humanitarian operations in Iraq and Afghanistan could threaten aid neutrality and put civilian aid workers at risk because anxious local residents could mistake them for military-linked—and threatening – external forces.

Catherine Bertini, former executive director of the United Nations World Food Programme, echoed these concerns over neutrality. She cited the simultaneous U.S. campaigns in Afghanistan – bombing and helping provide food aid to locals over the past decade – as an example.

During the recent U.S. military deployment after Haiyan, the International Coalition for Human Rights in the Philippines – a coalition of almost 60 organizations from around the world – issued a statement saying it was troubled by the U.S. military’s presence in the country. It cited the concerns of local residents who were fearful of anyone in a uniform, due to decades of fighting between the Armed Forces of the Philippines and many insurgency groups.

But as the security situation continues to deteriorate in many of the world’s humanitarian crisis areas, the role of the military will become more important — and more controversial.

Army Lt. Col. Herbert A. Joliat said troops can be an invaluable and even necessary asset to workers from non-governmental organizations, or NGOs, in conflict zones.

“A lot of the NGOs are coming in… but they’re coming in blind,” said Joliat, a member of the U.S. Army Special Operations Command’s 95th Civil Affairs Brigade, who supervised military humanitarian operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, “Without our teams on the ground, working with the local government and local security elements, really the NGOs wouldn’t know where to go and what to do.”

Also, according to an October 2013 report from advocacy group Humanitarian Outcomes, the rate of attacks on aid workers was still on the rise as of 2012, with the number of aid worker kidnappings growing four-fold over the last decade.

Some others question whether the military should continue to respond in humanitarian crises at all, given the budget deficit and its many other responsibilities.

Paul Hughes, a retired U.S. Army Colonel who led the military’s response to disasters including Hurricane Mitch and the Turkish earthquakes, said that the Defense Department’s unique skill set makes it a key player in emergency-response efforts. But, he says, saving the world isn’t in its core job description.

“The military has a culture where it knows how to organize,” said Hughes, who currently serves as the senior advisor for International Security and Peacebuilding at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP).

“While that can be a source of pride for the military, that’s not what the Department of Defense was established to do and has Constitutional obligations to do. It’s to provide for the defense of the nation.”