The geopolitics of fracking

WASHINGTON, D.C. — While recent debates about hydraulic fracturing have raged over potential environmental repercussions like earthquakes, gas leaks and water contamination in the U.S., the significant geopolitical effects of this huge shift in fuel production continue to play out.

Many have credited the fracking boom, which peaked in the last few years, with a new American independence. The thinking goes that with domestic production soaring, the U.S. is less dependent on other nations for energy supply and so less vulnerable to the demands and strife of oil-supplying countries.

For one, fracking has had an indirect hand in foreign policy. The Obama administration’s ability to impose sanctions on Iran in 2010 and 2011 can be linked back to the shale boom, according to Sam Ori, executive director at University of Chicago’s Energy Policy Institute. Ori spent several years at a Washington-based think tank focused on energy policy and national security and worked at the State Department prior to that.

“A big part of the reason why they [the Bush administration] didn’t ultimately impose really harsh sanctions on the oil industry is because they were concerned about what that would do to the oil market, the oil price and the global economy,” Ori said in an interview.

There was concern that the global market wouldn’t be able to compensate fast enough if Iranian fuel was taken off the market at that time.

“From an oil market standpoint, the shale boom really provided the flexibility to do that,” Ori explained.

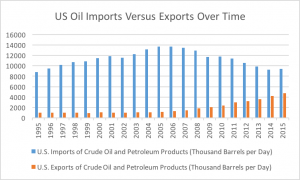

Still, there is a problem with the energy independence argument. Fracking has boosted the rate at which oil and natural gas can be extracted from wells, but despite now being one of the world’s top exporters, the U.S. still imports huge amounts of oil and petroleum products.

The U.S. exported more oil than ever in 2015: 4,750,000 barrels a day, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. That same year, the U.S. imported 9,401,000 barrels per day. When you compare that to 2005, the year with the highest imports in decades, at 13.7 million barrels a day, the difference is not as striking as you would expect, especially when U.S. exports for that year were only 1.2 million barrels a day.

Exports are in addition to domestic production consumed at home. For some perspective, in 2015, the U.S. used an average of about 19.4 million barrels of petroleum products a day overall.

“The fact that we’re so dependent on it means that we are still going to care about what happens in the Middle East,” Ori said.

If tensions come to a head between Saudi Arabia and Iran, “every major consuming country in the world will feel it mightily, and our military and our foreign policy apparatus are acutely aware of that, and that hasn’t really changed,” he said.

There is a lot of global instability revolving around energy security to be worried about. Collapses in oil prices have had dramatic impacts in Russia and countries throughout the Middle East where energy income accounts for huge proportions of government revenue.

About 99 percent of government revenue is generated by the oil sector in Iraq, according to the United Nations Development Programme. Imagine the impact of a collapsed oil market, then, for a country torn between rebuilding its economy to deter further unrest and dissatisfaction and spending millions to fight an active war on ISIS.

The fracking boom arguably played an unintended role in all of this geopolitical dislocation.

“I think you could definitely say that the huge increase in oil supply from the United States is certainly what triggered the price collapse,” Ori said. “A lot of these economies are so rigid and so unprepared for this. They had been planning for a world in which oil prices were going to be high forever because there was no cost-effective growing source of supply outside of OPEC.”

The new oil imbalance elicited less attention and a slower price response at first because the shale boom exports flooded the market at a time when a lot of oil came off line in the Middle East because of civil upheaval like the war in Libya.

“The shale boom sort of hid the impacts of those disruptions, but the disruptions also sort of hid the imbalance in the oil market,” Ori noted.

Clearly, energy production and politics will continue to have serious national security implications. And while fracking has been an inarguable boon for the American economy, there are important considerations to be made.

“The thing we could do the best would be to continue to diversify the fuels that we have in transportation, to work hard to make that a reality, to continue to not take big steps backward on fuel economy standards,” Ori said. “Our most effective insurance policy against all of this is really to make our economy less vulnerable.”

It is more important than ever to factor contingencies into U.S. energy policy and develop flexibility in order to weather what will continue to be an unpredictable global fuel market plagued by conflict and the increasing impact of climate change.