The Last Mile

DELGA, Burkina Faso — Seated in a homespun wooden chair outside her mud-walled home, Mariam Bargo spoon-feeds her infant son Rasmane a thin yellow porridge. Each bite brings grunts of satisfaction and smiles to his pudgy face.

The piping gruel smells and looks like finely ground grits but is made of corn soy blend (CSB) – a fortified cornmeal distributed by a U.S. Agency for International Development’s Food for Peace program to prevent malnutrition among the developing world’s most vulnerable populations.

Each month, Mariam makes the short walk along a narrow dirt path to a distribution point to receive her provisions – CSB, yellow split peas and vegetable oil, fortified with vitamins A and D. But the process that ultimately brought this meal here, all the way from a mill in Crete, Neb., began nearly nine months before – around the time Rasmane was born.

Tortuous journeys like this one are not uncommon in the food aid trade. The United States is the only donor that delivers the vast majority of the food aid it supplies in the form of in-kind commodities, shipped on slow-moving vessels to Burkina Faso and other remote locales – places that desperately need this supplementary food.

In villages like Delga in northeastern Sanmatenga province, malnutrition is prevalent – a 2010 Burkina Faso Demographic and Health Survey showed that more than one-third of the country’s children are chronically malnourished. Poor rainfall, infertile soil and temperatures that regularly climb above 100 F° even in winter limit agricultural production. The food that can be grown here – mostly sorghum and millet – doesn’t satisfy basic dietary needs, particularly for pregnant women and children.

Mariam is a 26-year-old mother of three, but Rasmane is the only one of her children young enough to qualify to receive food from a Food for Peace funded project called Victory Against Malnutrition, which targets children under two. As many children do here, 9-month-old Rasmane contracted malaria during the rainy season. But generally, Mariam says, he is healthier than his older brothers were, thanks to this food.

Her food’s journey began in February 2013, with the placement of a purchase order in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Kansas City Commodity Office, which procures the food from American farmers and millers that Food for Peace ships around the globe. The CSB was milled at a Bunge plant in Crete, Neb., before traveling south to the port of Houston. From there, the CSB was loaded aboard a Liberian containership – the H.S. Bach – that left Houston on June 7, 2013.

An accompanying shipment of vegetable oil left Houston a few days earlier on June 1 aboard another Liberian vessel, the E.R. New York. Both shipments headed northeast across the Atlantic, before stopping in the port of Le Havre, France, where they were transferred onto two different ships, for the second leg of the journey.

On July 5, nearly 265,000 pounds of vegetable oil arrived in Lomé, the coastal capital of Togo, on board the Patricia Schulte, a massive containership, nearly the length of 2 1/2 football fields. Shortly after on July 12, 265,000 pounds of CSB arrived on board the EM Psara. There, the shipments were loaded aboard trucks and took one week to make the 584-mile trip north to the Burkinabe capital of Ouagadougou. After spending two weeks tied up in Burkina Faso’s Customs office and another month clearing Ministry of Health inspections, the bags of food and boxes of oil were stacked onto pallets in a Ouagadougou warehouse compound in September, nearly 6,000 miles from the Nebraska mill where the CSB was produced.

Here, the food sat until mid-November, when it driven to Mariam’s village and several others near Kaya, just over 60 miles north. But it’s this last leg – the last mile – that embodies the difficulties inherent in delivering food aid to the people and places that need it most.

Chapter 1: Loading

(Drew Kann/MEDILL)

Roughly nine months after the initial order was placed in Kansas City, dozens of women are huddled in a Ouagadougou warehouse around tubs of corn soy blend, meticulously measuring and weighing the monthly rations by hand on electronic scales – 4.05 kg’s for the mothers, 2.25 for each child under two.

The food stored here, piled within feet of the corrugated metal roofs in each of the seven warehouses that comprise this facility, serves 113,000 beneficiaries in Sanmatenga province. But before it can be delivered, it all must be repackaged into the proper provision size, with “USAID – FROM THE AMERICAN PEOPLE” labels carefully affixed by hand.

This takes time and manpower – 30 workers to be exact, splitting five-hour shifts from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m., six days a week, all paid for by U.S. taxpayer dollars. Despite the cost, ViM’s top project official, Amidou Kabore, insists the process is vital to the operation.

“Since the target beneficiaries are very vulnerable people – pregnant and lactating women and young children – we need to be very careful to ensure that we are distributing quality food,” Kabore says.

The truck loading process is equally cumbersome. Without so much as a dolly or a loading ramp, nine men spend nearly five hours heaving bags into the truck’s splintered wooden bed, pouring sweat in the 102-degree heat. With its paint badly faded and coated in fine red dust, the truck’s better days have long since passed.

The ride to Kaya is slow going. Loaded to the brim with 23 metric tons of CSB, split peas and oil, the truck can travel no faster than 20 mph. The 62-mile trip – about the distance from Trenton, N.J. to New York City – takes nearly five hours.

At times, the thick black smoke billowing from the exhaust pipe obscures views of the landscape, which grows sparser as the truck heads north. The food reaches Kaya after nightfall and is parked in front of the project’s field office, where it sits overnight with two guards sleeping in the cab to protect the cargo.

Chapter 2: Drop off

The next morning, the truck crawls toward its destinations – 10 distribution points in the area surrounding Kaya, where food is dropped off and stored overnight until the next day’s distribution.

But getting the food to these sites is not easy. On the outskirts of Kaya, the uneven pavement ends abruptly, giving way to a stripe of red earth. In the dry season, these roads are barely passable, and even less so when the summer rains come.

“In August and September at the most difficult sites, we’ve had 15 or more days of delay in the distributions due to the quality of the roads. If you have to cross a river after a big rain, it is very difficult,” Kabore says. “People have to come to the main road to take the food with bicycles to the distribution sites, so it is not easy.”

Near the second drop-off at the village of Zorkoum, the parched soil has crumbled away on the left side of the road. A ditch blocks the truck from reaching the distribution site, and a motorcycle with a small bed attached must meet the truck on the main road to receive the food.

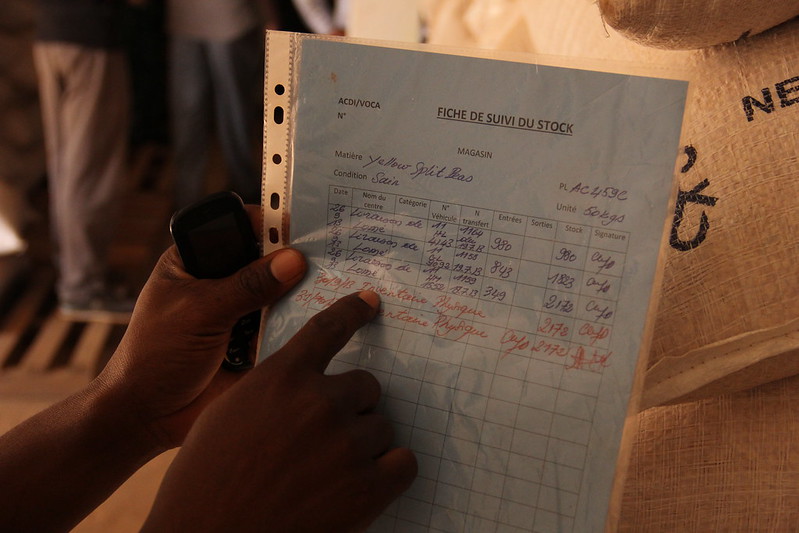

Inside the small, dimly lit warehouse, a group of men and women from Zorkoum and the surrounding villages are counting bags of CSB and split peas. One notices that three are missing from this shipment, in addition to the few bags that ruptured on the road during the unloading process. One of the village representatives, an elderly man named Noraogo Ouedraogo, makes clear that there is some urgency to this matter: without replacements, three beneficiaries will have to go without this food until next month.

“Since we will distribute the food tomorrow, we need to get the three missing bags this afternoon,” he says to the Victory Against Malnutrition staff assembled.

The villagers are assured by project staff that replacements will arrive before tomorrow’s distribution.

Chapter 3: Distribution

It’s 8 a.m. and already, a crowd has formed in front of the distribution warehouse near Delga. A large tree hangs over the warehouse, one of few in this desolate landscape. Women and children huddle beneath it, seeking respite from the searing heat. Their bikes are parked in a growing jumble nearby.

Some will not leave until after nightfall. Many have traveled considerable distances – three, six, even 10 miles by bike or foot – to receive this food.

“As much as possible, we try to limit the distance between the villages and the distribution site,” Kabore says. “We don’t want these women to have to travel more than 15 kilometers (≈10 miles) from their homes.”

A vibrant pop-up market has materialized to serve those waiting. Women make extra money by selling fritters made of local cereals and groundnuts, fried in hot oil above small wood fires.

Once a month, similar scenes play out at 45 other distribution sites served by the ViM project in Sanmatenga province.

The food distributed here is used as an incentive, part of a holistic approach to improving the food security and health of this population. One by one, women with their children wrapped tightly against their backs approach a table outside the warehouse and present a blue booklet to the ViM staff seated at a table. Here, they check to make sure mothers and their children have made the required monthly health center visits and attended nutrition seminars. If they have, they are handed a ticket to receive their rations, and join the next line. If they haven’t, the ViM staff investigates to find out why.

Chapter 4: The meal

Down the road from the distribution site, Mariam Bargo scrapes the last bits of CSB porridge from a green cup into Rasmane’s mouth. The child reaches for the spoon, eagerly awaiting each bite. His mother makes clear that she is thankful for this food, and to the people of the U.S. for providing it.

But this support will not always be here, a sobering reality that both Bargo and Kabore understand.

Victory Against Malnutrition is working on borrowed time. The project ends in 2016, and with it, all of the food distributions, health promoter visits and agricultural development initiatives.

“When the project ends, we will continue to feed our children with what we usually eat,” Bargo says, a porridge made of cereals, groundnuts and when available, fish. It’s a filling meal, but lacks some of the vitamins and micronutrients vital to healthy childhood development.

“But we don’t want the project to end,” she adds.

The residents of Sanmatenga province must make the most of the few resources they have, so in addition to food, the project provides beneficiaries with education about proper nutrition and farming techniques. Self-sufficiency is the goal, and Kabore is confident that by the time the food distributions end, the beneficiaries will have the knowledge and skills necessary to grow enough to feed themselves. But in Burkina Faso and other countries like it, the fight to end chronic food insecurity will not be won overnight.

“The needs are so high and the resources are not there. If we don’t have aid in this country, it could be a big problem,” Kabore says. “Without support, it will take longer to end the issue of food security.”