A realist approach to Russia

During his campaign and now in his transition to the White House, President-elect Donald Trump has been more than willing to buck Republican Party orthodoxy on numerous issues including free trade, immigration reform and entitlement spending.

His most radical deviation from the norm, though, is probably in the world of foreign policy.

Trump has promised a reversal or re-evaluation of America’s involvement in the Middle East, its commitment to NATO allies, and, most notably, its relationship with Russia. Unperturbed by U.S. intelligence community allegations that Russia hacked domestic political organizations and the perception that he is being manipulated by Russian president Vladimir Putin, Trump has vowed to warm the ice-cold relationship between Washington and Moscow.

Although that position has worried more than a few policymakers, some scholars, writers, and journalists hope Trump will make good on his promise to realign U.S. policy toward Russia. They belong to a school of thought in international affairs known broadly as realism, a strategic outlook guided by traditional power politics rather than concern for universal morality or human rights.

Famous practitioners of realism include George Kennan, who devised America’s strategy of containment of the USSR at the outset of the Cold War, and Brent Scowcroft, the national security advisor under Presidents Gerald Ford and George H.W. Bush. The most prominent foreign policy realist is probably Henry Kissinger, who as Richard Nixon’s national security advisor pursued détente with the Soviet Union and paved the way for renewed diplomatic relations with communist China in 1972.

Today, University of Chicago political scientist John Mearsheimer is an archetypal scholar of foreign policy realism. He believes Washington should pursue a strategy that focuses on America’s position in the global balance of power and avoids meddling in other countries’ internal politics or structure of government.

Realists like Mearsheimer reject what they call “liberal hegemony,” a worldview that sees the U.S. as the guarantor of global security and encourages leaders in Washington to engage in worldwide democracy promotion. Over the last 25 years, they claim, liberal hegemony has been the dominant school of thought within the foreign policy establishment and has caused policymakers to engage in foreign entanglements to the detriment of core national interests.

With some notable historical exceptions, realists have generally argued against U.S. military intervention in conflicts that don’t serve a core national security imperative. Scowcroft and Mearsheimer, for example, opposed the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, and Mearsheimer said that both the Iraq War and the U.S.-led intervention in Libya were foolish wars of choice, not strategic necessity.

At the dawn of a new administration, the realists are hoping their views will find favor with Trump’s foreign policy team. Mearsheimer believes improving Washington’s acrimonious relationship with Moscow would be a productive first step. In a recent piece for The National Interest, he argued that Russia is not a serious threat to U.S. interests and, in fact, could be a partner on several U.S. geostrategic priorities.

“The two countries should be allies, as they have a common interest in combatting terrorism, ending the Syrian conflict and keeping Iran (and other countries) from acquiring nuclear weapons. Most importantly, the United States needs Russia to help contain a rising China.” -John Mearsheimer

From day one, the Trump White House will have to manage several points of conflict with the Kremlin. Russia and NATO are currently engaged in a mutual escalation of forces in Eastern Europe, while Brussels has responded to Russian interventions in Ukraine with mobilization in the Baltic States.

The Iran nuclear deal also looms large in U.S.-Russia relations. Iran hawks in Congress—and, at times, Trump himself—have called for the pact to be renegotiated or done away with entirely, but Russia is party to the agreement and also happens to be one of Iran’s most steadfast allies. If it tries to alter the terms of the deal, the Trump administration could further alienate Moscow.

The Syrian civil war is the most precarious point of contention between the U.S. and Russia because it has the potential to suck both countries into direct military conflict. To avoid that outcome, Mearshimer believes, the U.S. must recognize Russia’s interest in Syria and let it “take the lead” in achieving peace there, even if that means keeping Bashar Assad in power.

“A Syria run by Assad poses no threat to the United States … both Democratic and Republican presidents have long experience dealing with the Assad regime,” he wrote. “If the civil war continues it will be largely Moscow’s problem.”

Such a policy realignment toward Russia might be unthinkable in many corners of Washington, but for proponents of foreign policy realism, it is long overdue.

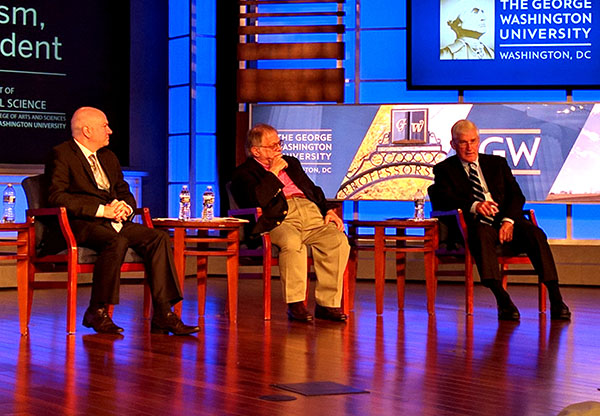

Several exemplars of the realist worldview came together last month for a symposium sponsored by The American Conservative, a right-of-center opinion magazine with a non-interventionist foreign policy bent. One of the central questions of the conference: How should the Trump administration manage America’s several conflict points with Russia?

Christopher Layne, a professor of international affairs at Texas A&M University, believes that a new era in history calls for a change in the way the U.S. conducts its foreign policy, regardless of who happens to occupy the White House.

“Change is coming to American grand strategy, whether we like it or not,” he said during a panel discussion. “I think actually — there are not a lot of us — there are some of us in the security studies field who have been making this point for some time.”

As Layne sees it, the unipolar moment of the immediate post-Cold War era has ended. America is now hemmed in, he believes, by at least three new factors: fiscal constraints on expansionist foreign policy, a domestic backlash to wars in the Middle East, and most importantly, the rise of China as a global power.

This new reality should prompt a concomitant reassessment of U.S. strategy and global commitments, Layne says, including longstanding military alliances such as NATO. He believes that NATO, which was a crucial bulwark against Soviet expansionism during the Cold War, has become a strategic liability and a source of unnecessary conflict between the U.S. and Russia. As Layne puts it:

“We can argue over whether there’s a role for Atlanticism in some form or another in American foreign policy, but I don’t think we can argue that NATO expansion, particularly to the Baltic States, was a huge strategic mistake.”

In the realist worldview, military alliances can offer protection but can also serve as “transmission belts for war,” and further militarization of NATO members on Russia’s border — let alone expansion of the alliance to Ukraine or Georgia — could drag the U.S. into a war with Russia that serves no strategic purpose.

Some of Trump’s past statements on NATO indicate he will pursue a more transactional approach to the alliance, perhaps by pressuring member nations to spend the mandated 2 percent of national GDP on defense. Layne sees that as a positive step toward incentivizing European allies — “free-riding security dependents,” as he calls them — to pay more for the continent’s protection. In recent weeks, however, Trump has softened his stance somewhat and reaffirmed America’s commitment to NATO.

If there is a unifying theme informing Trump’s foreign policy, it is “America First,” a slogan that hearkens back to the committee of the same name that opposed U.S. entry into WWII. It suggests a foreign policy retrenchment at odds with conventional Washington wisdom, which holds that America is the “indispensable nation” in a unipolar world and must project power and leadership to all corners of the globe.

Boston University historian and bestselling author Andrew Bacevich thinks the “America First” worldview, often maligned as isolationist, is now an appropriate guide for U.S. foreign policy strategy. “Donald Trump has revived the phrase and in doing so has imparted to it, I think, a legitimacy that it hasn’t had for the past 70 years or so,” he said at the symposium.

One of Bacevich’s main criticisms of the Washington foreign policy establishment is that has not let go of the premise that America and Russia are eternal antagonists on the world stage. A foreign policy built on the concept of America First, says Bacevich, would recognize that the U.S. is no longer locked in a global ideological conflict with Russia as it was with the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

“The vision that prevailed in the establishment was ‘We won. We are it militarily, we are it ideologically, we are it economically’…. I think that contributed to a sense of hubris.” -Andrew Bacevich

Both Layne and Bacevich are taking a wait-and-see approach to the new administration’s Russia policy. Trump has indicated, to much consternation in Washington and Brussels, that he will seek some measure of conciliation with Vladimir Putin. To what extent a warming of relations is possible remains unclear, but realists hope that a Russia-friendly Trump administration will acknowledge areas of mutual concern.

Nikolas Gvosdev, a professor of national security studies at the U.S. Naval War College, is one such cautiously optimistic scholar. He believes that Washington’s Russia policy has lacked a coherent structure with the ability to span presidential terms. Every administration since Reagan, he says, has had to re-invent the wheel with so-called “resets” that inevitably go south.

“We’ve had too much ad-hockery in the U.S. Russia relationship over the past 25 years… It’s not how Russia conducts its relations with most other countries,” Gvosdev said. “They have their strategic dialogue with Germany, they have their strategic dialogue with India…we need to have something like that here.”

According to Gvosdev, if Washington wants a less hostile relationship with Moscow, it must accept that Russia has a set of strategic precepts it is not willing to change. Much like the U.S., Russia insists that the internal affairs of its government are off-limits to outside interference, it has legitimate interests in its neighbors, and it has the right to secure favorable outcomes for its allies and clients. The Trump administration’s recognition of those claims, Gvosdev says, would be a major step toward repairing the frayed bilateral relationship.

The American Conservative Senior Editor Daniel Larison agrees that U.S. policy toward Russia must be consistent, and he also argues that it must distinguish between vital and tangential interests. Larison is an outspoken critic of American liberal hegemony because he believes it no longer redounds to core national interests. Nowhere is that more clear, he says, than U.S. policy toward Russia, especially in Syria and the NATO countries on Europe’s eastern edge.

“Washington has sought to compete with Moscow in places that matter greatly to them, but matter very little to us,” Larison said. “We’ve seen that with attempted NATO expansion deep into the former Soviet Union, and we’re seeing it again today in Syria.” That imbalance, in Larison’s estimation, inevitably exposes America and its allies to unnecessary risks and ensures that the U.S. will be seen as the loser in conflicts it does not have any real interest in winning.

Larison, who is a dovish breed of realist, is not optimistic about the chances for significant easing of tensions between Washington and Moscow over the next four years. He did acknowledge that Trump’s national security advisor, Michael Flynn, has suggested working with Russia on counter-terrorism and other security matters, but he also pointed to Flynn’s past writings as evidence that the former Defense Intelligence Agency chief sees Russia as an enemy.

“In a book [Flynn] co-authored with Michael Ledeen, he said he believes ‘Putin fully intends to do the same thing as, and in tandem with, the Iranians: pursue the war against us,’” Larison said.

Despite those doubts, Larison and his counterparts at The American Conservative’s symposium were unanimous in their view that the danger of a direct confrontation with Russia is now less than it would have been if Hillary Clinton had won instead of Trump. They will have to wait until January, however, to find out if any other realist policy preferences are adopted by the White House.