[field name=”sidebar”]

SECURITY FOR HOSTILE ENVIRONMENTS

OVERVIEW

Different stories bring their own risks. The degree of risk is often situation specific. And the riskiest stories are often not what many may think.

SECTIONS

Journalists also need to take responsibility for their own security. The changing economy of the news business makes it increasingly harder for journalists to rely on security advisors. Instead, both international and local journalists need to assess their own risks and needs in advance of embarking on a dangerous story. The narrative below offers some suggestions, and more specific tips can be found in the individual links.

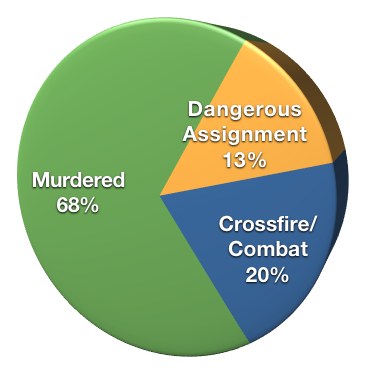

Over the past 20 years, one in five journalists killed on the job around the globe died on a battlefield covering armed combat of one kind or another, according to figures compiled by the Committee to Protect Journalists. More than one in seven journalists were killed covering violent protests or other dangerous situations. But these two kinds of deaths — combat and other dangerous assignments — still add up to less than one-third of all journalists killed while reporting.

Instead, more than two out of three of the 1003 journalists killed worldwide over the past two decades have been murdered outright in direct retaliation for their work. Of course, almost all of the murdered journalists — no less than 94 percent — were local journalists killed while reporting within their own communities or nations.

Portraits of journalists killed in crossfire / combat. More details at the Committee to Project Journalists. (Photo via CPJ)

Foreign correspondents should be mindful of the risks that their local colleagues —along with many of their families — face in nations such as Iraq, Somalia, Mexico or the Philippines. In fact, even in war zones such as Iraq, Afghanistan and Somalia more journalists have been murdered than have died under any other circumstances. Moreover, murders have dominated journalist fatalities every year going back decades.

In recent years, however, the risks faced by both local and foreign journalists have become more aligned. Both a Sky News cameraman, Mick Dean, and local journalists like Mossab al-Shami have been killed in 2013 since the military ouster of President Mohamed Morsi in Egypt. Within the region, Syria has become the dangerous nation in the world for journalists. Five foreign correspondents and at least 45 local journalists have been killed in Syria since its civil war began in 2011.

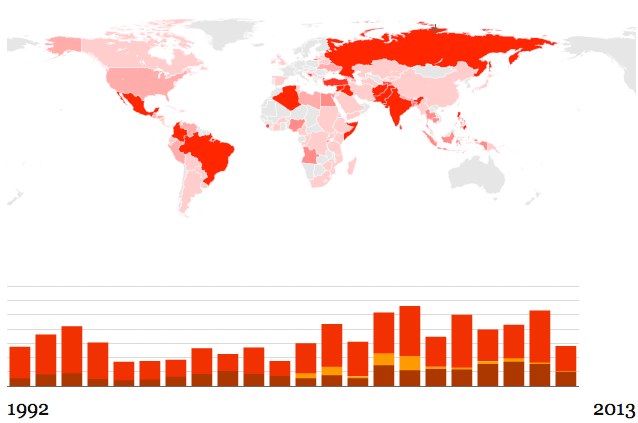

Location and number of journalist deaths per year.

The year 2011 began a trend where both foreign and local reporters have increasingly followed the same international events. The many popular revolts in Arabic-speaking states associated with the so-called “Arab Spring” led to a record of 38 percent of all journalists killed worldwide that year who died while covering violent protests and other dangerous situations.

How 1003 journalists have been killed since 1992.

SOURCE: Committee to Protect Journalists.

Fatalities are hardly the only danger journalists face. The group sexual assault of CBS News correspondent Lara Logan in February 2011 in Egypt’s Tahir Square finally lifted the stigma of discussing such attacks. In its wake, dozens of journalists –mainly women but also some men — came forward to Lauren Wolfe, then with CPJ and now with the Women Under Siege Project, to discuss how they were sexually assaulted or attacked while reporting.

Journalists can take a number of steps to avoid and deter sexual assaults, many of which are detailed in CPJ’s chapter on Sexual Violence in its Journalist Security Guide. The steps include:

- Enhanced situational awareness, or simply looking for signs of trouble before they start.

- Using body language and tone of voice to help deter potential assailants.

- Working in teams so individual is always keeping an eye on the crowd along with movements and potential escape routes beyond.

- Moving in groups to navigate through a hostile crowd.

- Finding ways to change the dynamic of a situation to either escape, or get change the focus of attention.

Training in such techniques is also recommended.

Journalists should also be mindful of more common hazards as well, like traffic accidents, which the World Health Organization reports as a leading cause of death, especially in less developed nations. The well-respected journalist Elizabeth Neuffer of The Boston Globe died in a car accident in 2003 in Iraq.

Food poisoning is another common hazard to be avoided.

Any journalist — foreign or local– needs to thoroughly research and consider the risks of any potentially dangerous story in advance. The Committee to Protect Journalists’ Journalist Security Guide published in 2012 and now available in English, Spanish, French, Arabic and Somali may be one place to start. I am the main author of the CPJ guide; many of the same topics covered here and covered there in more depth.

BEFORE YOU GO

No matter the story, journalists should take care of a number of matters before they depart or even begin reporting. One is to make sure one’s press credentials are up to date. In the case of stringers, it may be wise to ask for a letter of support from a particular news outlet.

An even more important matter will involve securing appropriate insurance, and this will require considerable research in advance. There are different kinds of insurance. The most important may be to have health insurance in your home nation in case you need any medical care due to injuries once you are back home. One may also purchase medical evacuation insurance, although the rates can be prohibitively expensive. And being evacuated from a particular area after an injury is almost always less important than receiving good and timely emergency care after being injured. The Paris-based press freedom group, Reporters Without Borders, offers limited, but affordable health and life insurance for freelancers.

Life insurance for anyone with dependents is obviously recommended, although an amazing number of experienced journalists continue to work without it. In 2012 in Libya during the revolt against Muammar Gaddafi, South African photojournalist Anton Hammerl was shot and killed in an attack by government troops. Colleagues later raised (a relatively meager) $135,000 for his widow and three young children as the veteran photojournalist had been reporting from the battlefield uninsured.

Hostile Environments Training (discussed in more detail below) can also help lower insurance rates for health and life insurance coverage in conflict zones.

Keeping physically fit and maintaining a proper diet are always important. Some journalists practice exercises such as push ups, sits up, and crunches that can be done without attracting attention in one’s hotel room.

Any journalist expecting to travel internationally should research and consult medical professionals to make sure that all required or recommended vaccinations are up to date. A 10-year tetanus shot is recommended anywhere. For travel to some areas an antimalarial medication may be recommended. For other areas, vaccination against polio, hepatitis A and B, yellow fever, and typhoid may be recommended. Vaccination for yellow fever is required for travel to some West African and Central American nations. Meningitis and polio vaccinations are required for travel to Mecca in Saudi Arabia. The World Health Organization provides updated disease distribution maps.

Journalists may also wish to research whether to use iodine or chlorine pills, or filtering devices may be recommended for travel to different areas. Antiseptic cream and anti-fungal cream could also be useful. Knowing your blood type and carrying a blood donor card or some other way to indicate it –- including carrying a laminated card around your neck if covering combat or other high-risk situations —- may also be a good idea.

EQUIPMENT AND TRAINING

Depending upon the story and situation, safety gear, including body armor and a helmet, may be recommended. This is certainly true anytime a journalist is traveling with combatants who themselves are equipped with protective gear. But it could be a liability in other areas where a journalist is less likely to face the risk of crossfire than being targeted by criminal actors. In such cases wearing safety gear could only make one stand out to look more like, say, an anti-drug agent than a reporter.

The U.S. National Institute of Justice has developed a six-tier rating system used by most body armor manufacturers. Journalists make obtain and carry a vest rated for the kind of weaponry in use in the particular theater. A police-style vest designed to stop handgun bullets, for instance, will not be effective against high-powered military rifle rounds. In many cases, there is also a trade-off between the weight of a vest or helmet, and its protective capabilities. Technology continues to evolve, so journalists must research updated available options.

Helmets are also recommended for military situations, although wearers should know that they are designed to protect against shrapnel and not stop rifle rounds.

For journalists covering riots, gas masks may also be recommended. Makeshift masks made of cloth and liquids such as vinegar or citrus juice can also be useful. Anti-stab vests along with protective, baseball-style caps are also available.

Not even the most precise language about how to specifically avoid or navigate particular situations can substitute for actual training. There are a number of providers of hostile environment training. (Full disclosure: My firm, Global Journalist Security, provides integrated training involving physical, digital and emotional self-care awareness and protocols for a variety of hostile and other threatening environments.) Such training tends to prepare journalists for covering combat along with teaching them emergency first-aid.

The journalist and author Sebastian Junger has founded Reporters Instructed in Saving Colleagues or RISC to provide emergency first-aid training to combat photographers. Junger set up RISC after his friend and colleague Tim Hetherington died of an open femoral wound in 2011 after being wounded covering fighting between government and rebel forces in Libya.

The journalist and author Sebastian Junger has founded Reporters Instructed in Saving Colleagues or RISC to provide emergency first-aid training to combat photographers. Junger set up RISC after his friend and colleague Tim Hetherington died of an open femoral wound in 2011 after being wounded covering fighting between government and rebel forces in Libya.

A number of news organizations have begun working with some private firms to provide training better suited to many of the contingencies that journalists face. They include more focus on covering matters like civil unrest and the sexual assaults that can occur in mob situations. My firm, GJS, draws from self-defense protocols to help journalists avoid and deter sexual assault. Students taking the “Covering Conflicts, Terrorism and National Security” Class in the Medill Washington Bureau receive training from Centurion Risk Assessment Services.

GJS and the International News Safety Institute both also include surveillance awareness and detection as part of their curriculum when training journalists in nations like Mexico, Somalia or Pakistan where journalists are often targeted for murder.

RISKS AND CONTINGENCIES

Assessing risk is something that every journalist does on a nearly constant basis when in the field. How to best approach a story? What risks are possible or likely to be faced? How to mitigate against expected or possible dangers? What options exist should a potentially dangerous situation get worse? What exit routes may be available? These are all questions that should be considered in advance.

What kind of profile to assume is another question. Would it be better to blend in or stand out? What should one be prepared to say if certain questions are asked, or if a journalist is interrogated? Is a cover story recommended or necessary? What about one’s laptop computer? Could the information there be incriminating for journalists or their sources? (See Digital Security Basics for Reporters that I wrote for Medill National Security Zone.) What are the potential risks of being perceived to have misled others?

What are the risks to one’s sources or people interviewed or met along with the way? What are the risks to any potential fixers or drives who may be employed?

Should one embed or travel with a particular armed group or authority? Should one at least check in with any such group or authority? Or would it be better, or necessary, to travel and operate alone?

Thinking through contingencies in advance is always recommended. CPJ provides a risk assessment form that was developed in collaboration with researchers at Human Rights Watch (see right — click lower right corner to see full screen). Filling it out in advance is an important exercise, and everyone involved in the reporting should be part of the process.

Preparing a contingency plan in advance of any situation is also recommended. What should those who are aware of journalists’ travel plans do, if they fail to come back on time? Journalists should have a contact person or people who know their travel plans and expected time of return. Journalists should also develop in advance methods to communicate with editors and other contacts. (Here again the Digital Security Basics for Reporters guide may be helpful.)

EMOTIONAL AFTERMATH

Learning how to navigate through emotional stress is as important as learning how to navigate combat or civil unrest. Journalists need to realize that having some kind of emotional reaction to an abnormal, highly disturbing event is an entirely normal response. The greater risk may lie with journalists who experience little or no reaction in the moment only to have their emotions catch up with them later.

Signs of stress may vary. They may include anxiety, irritability, withdrawnness or emotional numbing, depression, sadness or anger. Some journalists may find their ability to work curbed or impaired. Even more journalists seem to find that they only feel normal while they continue at risk. Increased consumption of alcohol and drugs are also both common. So are sleep disorders. Nightmares are also common, although many journalists and others report that nightmares, as long as they do not continue unabated, may provide for a valuable release.

The troubling feelings may pass or not. More than one in eight journalists in general, and more than one in four conflict reporters, have shown signs of post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD, according to separate studies.

Experts of all kinds seem to universally agree: what is important is to find a way to address the feelings or emotions surrounding the trauma. Mind-body practitioners have begun to borrow from martial arts and other disciplines to provide journalists and other first-responders with simple but effective breathing and other mind-body tools to help process the energy of trauma in the moment. Following trauma, a number of mind-body techniques including yoga, tai chi, qi gong and meditation have also been effective, according to the U.S. National Institutes of Health National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

Clinicians have developed a number of more traditional ways to help individuals address and process trauma. Some treatments involve no more than simply talking through one’s feelings with a therapist. Others have benefited from group therapy. Yet others have benefited from simple but effective mind-body techniques administered by a therapist like Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing known as EMDR. Other individuals, especially those who may already be on or require medication, have benefited from the guidance of a psychiatrist.

The Dart Center for Journalism & Trauma provides of wealth of resources for journalists to consider. The guide Tragedies & Journalists by the Oklahoma-based editor and journalist Joe Hight and myself might be one place to start. The Dart Center also provides a guide to help journalists choose a therapist.

The Dart Center for Journalism & Trauma provides of wealth of resources for journalists to consider. The guide Tragedies & Journalists by the Oklahoma-based editor and journalist Joe Hight and myself might be one place to start. The Dart Center also provides a guide to help journalists choose a therapist.

The good news is the treatments work. In recent years, researchers, many of them working with U.S. military veterans, have established the phenomenon of post-traumatic growth.

“We’re talking about a positive change that comes about as a result of the struggle with something very difficult,” University of North Carolina at Charlotte psychologist Lawrence G. Calhoun told The Washington Post in 2005. Post-traumatic growth involves a better sense of self, relationships with others, abilities to cope, and appreciation of life after not only recovering, but emerging enhanced from having overcome a traumatizing experience.

“It is positive change experienced as a result of the struggle with a major life crisis or traumatic event,” write Calhoun and other UNC researchers.

WORTH THE RISK?

Finally whether and to what a degree a journalist may wish to risk his or her life, not to mention the wider impact to loved ones, is a highly personal decision. One mantra sometimes heard is, “No Story is Worth Dying For.” This view was perhaps best represented by David Schlesinger, a veteran journalist then with Reuters, in a keynote speech to the London-based International News Safety Institute in Athens, Greece in November 2010.

“I am asking you today whether we, the journalistic community, need to reassess our need to be in the midst of danger,” said Schlesinger. “Sometimes, of course, the benefits to transparency and understanding are such that we indeed must be right there,” he added.” But let’s be honest. Sometimes those benefits are not there and the reasons for being in harm’s way are less noble: competitive pressure, personal ambition, adrenaline’s urging.”

Finding the right balance remains a challenge, even for some of the most experienced and respected reporters.

“In an age of 24/7 rolling news, blogs and twitters, we are on constant call wherever we are. But war reporting is still essentially the same — someone has to go there and see what is happening. You can’t get that information without going to places where people are being shot at, and others are shooting at you,” said Marie Colvin, who by then had already lost an eye to shrapnel in Sri Lanka, at a memorial service for fallen colleagues at St. Bride’s Church in London, the same month as Schlesinger’s speech in Athens.

Little more than a year later Colvin herself was killed.