Global action needed to prevent water-fueled conflicts

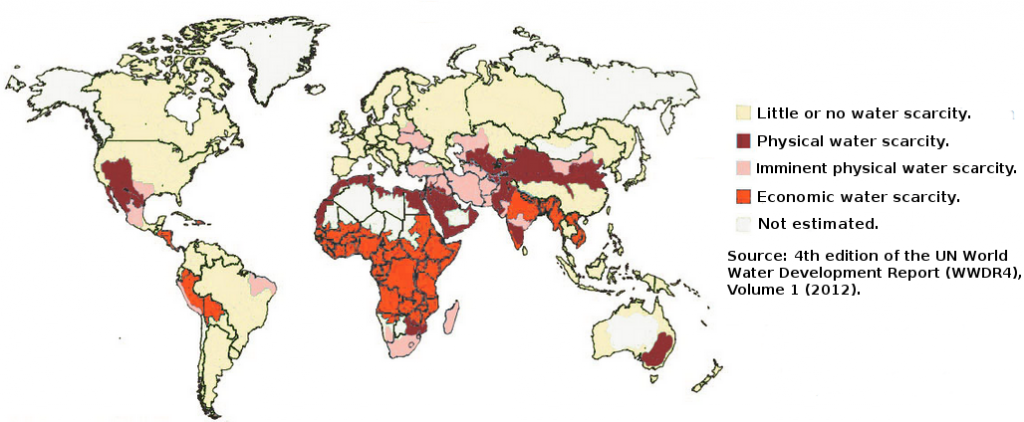

If international tensions seem to rise over oil and coal, imagine the stakes over a resource people literally cannot live without. Water stress is an increasing reality in many parts of the world, and the instability that goes along with it has the potential to leave no nation untouched.

“I don’t think we talk about what some of the projected consequences will be and how bad it could get with climate change and population growth and urbanization and so on,” said Gabriel Eckstein, a professor at Texas A&M University who specializes in water law and policy.

“We’re not anywhere near ready to handle those situations,” added Eckstein, who has served as an adviser to a number of U.N. agencies and the U.S. Agency for International Development on water issues.

The impacts of water stress could slow economic growth by as much as 6 percent of GDP in East Asia, the Middle East and Central Africa by 2050, according to a recent report by the World Bank Group.

Last year, a study using NASA data found that 21 of the earth’s 37 largest aquifers – huge storehouses of water underground – have been depleted past sustainability tipping points. Researchers considered 13 of them distressed enough to threaten regional water security, the worst being the Arabian Aquifer System and another in northwestern India and Pakistan.

India has long been experiencing a widespread drought, devastating agriculture and pushing farmers to suicide or to overcrowded cities in desperate search of alternative income. The country – with almost one-fifth of the world’s population – has the greatest number of people without access to safe water, according to a 2016 report by Water Aid.

“There’s a dawning realization that this is an incredibly important issue,” Betsy Otto, global director of the water program at the World Resources Institute, said in an interview. “Climate change is really showing its impact on fresh water.”

World leaders are starting to realize how integral water is to maintaining stability and how dangerous ignoring the impact of its absence could be. The High-Level Panel on Water was launched at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January to oversee and collaborate on sustainable water management and equal access.

In April U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and World Bank Group President Jim Yong Kim appointed 10 Heads of State and Government and two special advisors to the panel, including Australia’s prime minister, Malcolm Turnbull, and Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina of Bangladesh, both from drought-ravaged countries.

The U.S. Department of Defense issued a report in 2015 on the most serious climate-related risks each Combatant Command faces and how they plan on responding to them.

It’s a multidimensional issue to tackle. Water touches every aspect of life, from irrigation to industry to sustenance. Many direct conflicts are born of disputes over water, and access has even been wielded as a weapon in Syria among others places.

Since 2015, rebel groups have periodically cut off spring water and threatened to blow up the supply entirely if government forces approach, according to a chronology of water conflicts by the Pacific Institute.

But while water gives rise to tensions, disagreements resolve peacefully more often than not, and historically, cooperation is more common than conflict, a water dispute database out of Oregon State University shows.

The bigger threat – and the more difficult to deal with – may be the systemic socioeconomic consequences of stressed water resources.

“Water can be a chronic or slow underlying crisis that can lead to lots of challenges,” Otto said.

International regulation and cooperation over water is still far from effective or adequate. For example, there is yet to be a consensus on the “human right to water,” and international law on transboundary rivers and lakes is mostly vague, Eckstein said.

When it comes to groundwater – found in underground aquifers – there is even less clarity given that people didn’t start seriously pumping it until the second half of the 20th century. It is still unknown where and how big all the aquifers are. It takes time and technology to find and monitor them.

So far there are more than 600 transboundary aquifers, and Eckstein can count the number of full, formal treaties over groundwater on one hand, he said.

For instance, with one minor exception, the U.S. and Mexico have reached no agreement over the groundwater on their border.

“We’re pumping out of those aquifers even though we don’t know how much water is in those aquifers, and we have no agreement on how to even talk to each other about what we’re doing,” Eckstein said.

Still there has been progress, and the emphasis on water security issues by international agencies like the U.N. and the World Bank mean more time and resources will be devoted towards mitigating water stress and conflict through aid programs and NGOs.

“It focuses resources and development aid towards those issues, towards those questions for sure,” Otto said.

There have also been creative solutions through collaborative projects. The U.S. helped pay for a dam built on the Columbia river in Canada because it provided Americans flood control and electricity at a reduced rate.

International cooperation and data sharing is especially important for poorer countries who may not have the technical or financial capacity to vastly rebuild or reshape their water infrastructure.

“Maybe there’s some positives that will come out of this water stress in terms of innovation and efficiency,” Eckstein said.

It’s a challenging issue to address, especially in the developing world, “but it’s doable and it’s necessary,” Otto said. “We can’t continue to act like we can just get by with business as usual because that’s not the world we’re living in anymore.”