Public schools in California have strict building codes for earthquake protection, but state regulators have been lax with their oversight, according to reports by California Watch, a Berkeley-based independent investigative journalism project.

The Midwestern U.S. is, like California, prone to earthquakes, specifically around the New Madrid Seismic Zone (NMSZ). What are the earthquake risks to public school buildings in the eight-state region?

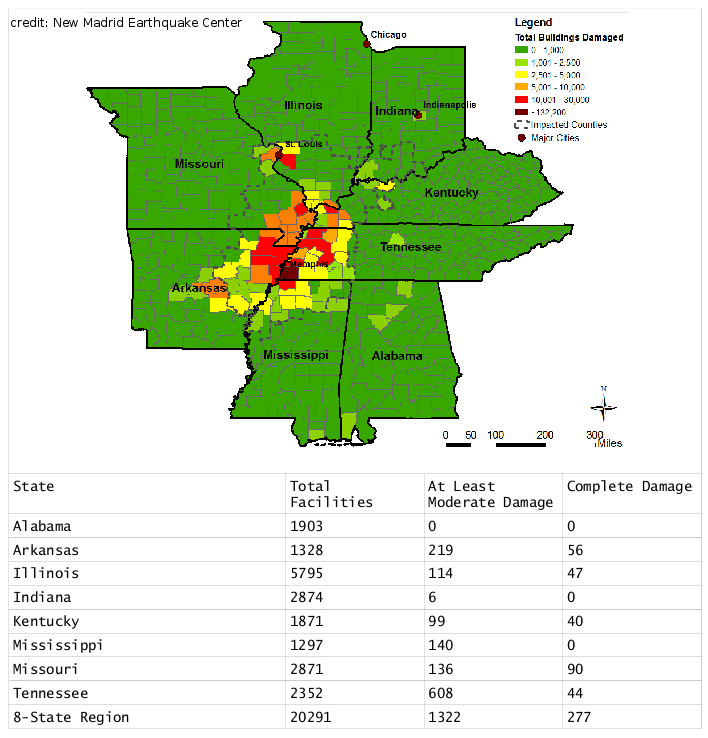

The zone, whose epicenter is New Madrid, Mo., includes Memphis, Tenn., St. Louis, and parts of the states of Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Alabama and Mississippi.

A recent study appraised the condition of public buildings, including schools in the NMSZ.

The October 2009 report by the Mid-America Earthquake Center at the University of Illinois is of a simulated magnitude 7.7 NMSZ earthquake, technically a rupture along the full lengths of all three of the New Madrid faults.

The report estimated that out of 20,291 schools in the region, 1322 would have major structural damage and 277 would be destroyed.

While the report offers numbers there are questions about the real degree of risk.

In California the Field Act has been in place since 1933. It was passed after a magnitude 6.3 Long Beach earthquake severely damaged an estimated 75% of southern Los Angeles school buildings.

The Field Act requires “that schools be built to a higher standard than regular buildings,” according to Mary Lou Zoback, an earthquake risk analyst with the Newark, Calif., firm Risk Management Solutions.

The schools that fared poorly in the 1933 earthquake were brick schoolhouses like the first U.S. schoolhouses built in quake-less New England.

Child deaths were averted in the Long Beach quake only because the March 10 temblor took place at 2 o’clock in the morning.

“Many schools in the Midwest are brick,” Zoback believes. Brick is unreinforced masonry that gives easily when the ground shakes. Unreinforced masonry is banned for public works projects in California cities.

Of the NMSZ states, only Arkansas has special seismic construction codes for its public buildings.

In January 2008, Arkansas considered adding additional earthquake safety provision to public building codes, upping the codes to California-levels, something FEMA recommends.

The Arkansas codes were not changed when the business community objected to the expense it would require, according to Seth Stein, a Northwestern professor of seismology,

Stein wrote the 2010 book, Disaster Deferred: How New Science is Changing our View of Earthquake Hazards in the Midwest, and he feels the NMSZ risks are overstated. Quakes occur frequently in the Midwest, mostly in the NMSZ, but there is little reason for concern, Stein believes.

The magnitude 2.5 earthquake that occurred 60 miles south of St. Louis in northern Arkansas in January 2011, was, according to Stein, a distant aftershock of the magnitude 7.0 New Madrid earthquake that occurred in 1811.

His research shows that very little energy is currently stored in the fault system and there is practically no imminent danger to the region.

Floods and tornadoes are far more dangerous to population centers in the region, Stein said, and FEMA wants states to build to 100-year flood levels and to 2500-year earthquake levels, at exorbitant cost.

The return on public investment for earthquake retrofits are minimal, Stein feels, asking rhetorically, “Would you rather put steel in your building or would you rather hire teachers?”