After you and thousands of others have run hundreds of miles to prepare for the big race, public safety officials are using that same big race to prepare for potential disasters. Be glad. It’s making both your race day and your community safer.

Big races are a big opportunity for the city’s emergency management services (EMS). “They know this event happens. They know it’s every year on this day,” says George Chiampas, medical director for the annual October Bank of America Chicago Marathon and the spring Bank of America Shamrock Shuffle, an 8-kilometer race. Each race counts more than 40,000 runners.

“It provides them an opportunity to test their technology and test their preparedness,” says Chiampas, pointing out that with so many runners and spectators flooding city neighborhoods the different EMS agencies – police, fire, hospitals, ambulance providers, public health, plus city parks, traffic management, Chicago Transit Authority, American Red Cross – have to communicate and work together effectively.

Marathons and other road races with lots of participants have developed a symbiotic relationship with the emergency management and public safety organizations in the cities where these events take place.

Fargo, North Dakota, had 10,000 runners participating in the city’s same-day marathon and half-marathon on May 21. It was a cool, but humid day. Runners inexperienced with how humidity taxes the body might add a layer. As a result they faced a real risk of overheating despite the comfortable temperature. “People don’t feel it right away,” said Fargo Marathon race director Mark Knudson.

A total 80 runners came through the medical tent at the finish line, including a rush of them when a mass of finishers from both races came in at the same time.

Fargo’s Sanford-Merit Care Hospital emergency room was full then too. The city EMS was also taxed. But it’s something they planned for.

The marathon has become an educational and practice event for the hospital, said Knudson. “Over the years it’s become something that they’ve learned a lot from.”

Comparing marathons, Fargo doesn’t go to anywhere near the logistical lengths that Chicago does, but it is still sizable.

With more than 20,000 runners participating in five different races, no other event on the Fargo calendar brings in as many out-of-town visitors. Fargo does take into account the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) National Incident Management System (NIMS) framework for inter-agency operations but doesn’t follow it as comprehensively as Chicago does, though that may change, according to Knudson.

NIMS is at the heart of what happens in Chicago on marathon race day. Chiampas said that the NIMS command structure is something that FEMA recommends strongly, “It basically means that there is a collaboration and communication between all organizations in managing any sort of a mass event – police, fire, FBI, traffic management, EMS.”

All the organizations fall in line under a single command hierarchy and use one messaging system. Chicago’s marathon system, Chiampas feels, is state of the art.

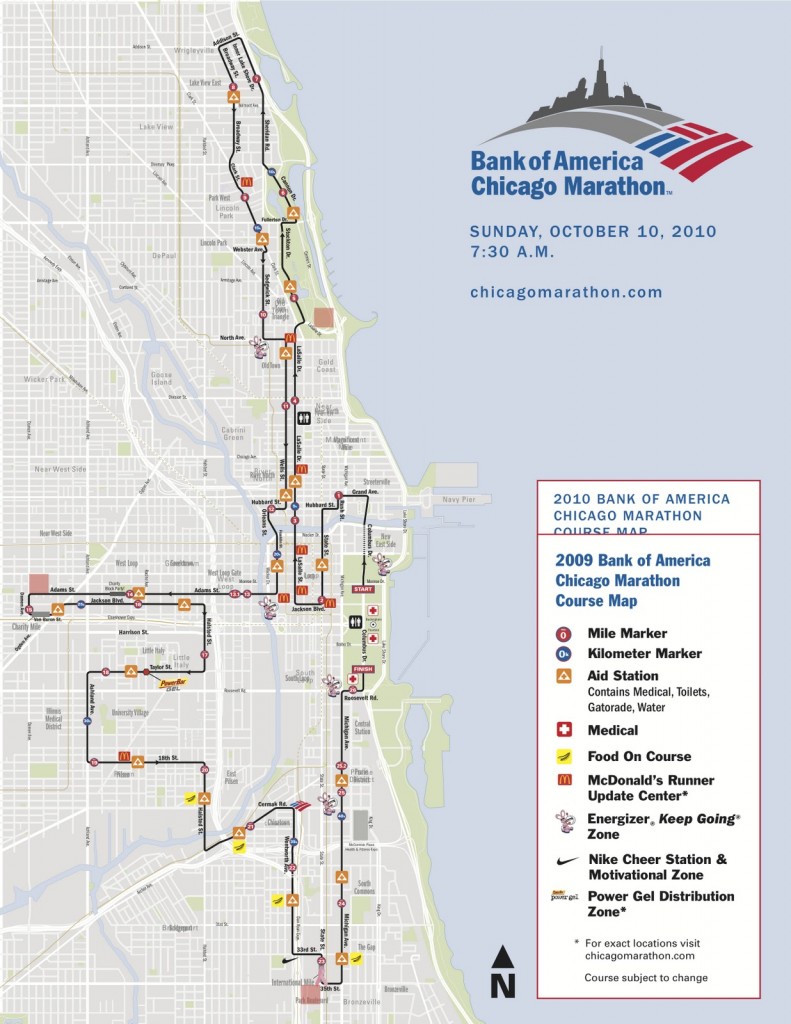

The main command center, the Joint Operations Center, runs out of the city of Chicago’s Office of Emergency Management and Communications (OEMC) 911 facility downtown. The race also has a forward command center near the race start and finish in Grant Park. A third mobile command center, owned by OEMC, is on the race course.

All of it is necessary. The race will have 45,000 runners, 12,000 volunteers and 1.7 million spectators, and the city could potentially have many more things to deal with at the same time. “There may be a baseball playoff game. There may be a fire. There may be a gas leak. There may be a robbery,” Chiampas stopped himself.

Each non-marathon situation has to be dealt with, “How is that an incident? How can it affect the marathon course?” Chiampas’ priority is clear, “The number one thing anytime we have an event is safety – safety for our runners, safety for the citizens of Chicago. We need to make sure the city is functioning at the same time as this event.”

But what happens when the details coming in about an event are ambiguous, and there’s no clear-cut immediate response. That’s when the race leans most heavily on its city partners.

Every day the Chicago OEMC gets ambiguous information, and on race day, for them, it’s the same set of operating procedures. “They have ways to verify certain information, and without going into detail, we have that capability,” said Chiampas. “Because we’re working as a team in a unified command approach it allows us to respond appropriately with all of the knowledge that you need.”

Everyone involved knows that they will be called on to respond to something, and the unified command meets year-round, intensifying preparation in the two months before the race’s October calendar date. Over the past 3-5 years more and more resources go to safety management.

Chiampas feels what’s special about the system is how public and private organizations work together. “We have a tremendous amount of respect. We work well together,” he said, “that’s the basis for doing this well.”

It is, he thinks, a template for how a risk-filled world can take care of itself.

”You’re going to need private entities to provide water and resources. We can’t expect our EMS system to do this on its own. We also need the citizens to be involved,” Chiampas said.

If everybody does their share, and understands what their responsibility and their role is, the system works, he feels.

But practice and preparation are crucial. The Chicago Marathon provides the city an opportunity to test all of its EMS systems and at the same time provide critical safety services to hundreds of thousands of spectators, tens of thousands of runners, and thousands of volunteers. “There’s no small numbers. And everyone expects the best response, and best practices in terms of how they’re dealt with. That’s what we’re measured up to.”