WASHINGTON — A strange thing happened on the night of the Iowa caucuses, and it wasn’t that Rick Santorum and Mitt Romney were vying for first place by a razor-thin margin.

WASHINGTON — A strange thing happened on the night of the Iowa caucuses, and it wasn’t that Rick Santorum and Mitt Romney were vying for first place by a razor-thin margin.

It was that Ron Paul, on the biggest evening in primary politics, decided to tackle the smallest issue in primary politics.

“And too often, those who preach limited government and small government forget that invasion of your privacy is big government,” he told supporters after finishing third in the first-in-the-nation contest. Under the Obama administration, “civil liberties are being trashed,” he later added to heavy applause.

The libertarian-leaning candidate’s campaign has injected civil liberties into the political discourse, but it has also unveiled an inconvenient truth at the same time: Privacy is not exactly a hot-button topic for presidential contenders.

For Dennis Johnson, a professor at The George Washington University’s Graduate School in Political Management and a former political consultant, civil liberties are not even a consideration on the campaign trail.

“There are certain things you just don’t talk about,” he said of making privacy a major plank of any political platform. “You just kind of shut up about those kind of things.”

A spokesman for the Pew Research Center, which gauges public opinion on and media attention to political issues, said the organization doesn’t “have anything recent on civil liberties.” He pointed to the center’s most recent mention of the term “civil liberties” — a broader report on the generation gap in voting patterns published last November.

The topic’s absence from the national conversation doesn’t surprise Jim Harper, director of information policy studies at the libertarian-leaning Cato Institute. Calling privacy a “small corner of public policy,” he dismissed the notion that the GOP presidential frontrunners would incorporate it in their stump speeches any time soon.

“The main candidates essentially pose no benefit to civil liberties,” Harper said. “They won’t be doing any favors for civil liberties.”

It’s easy to see why privacy is an especially thorny subject in a Republican primary that has turned into a conservative litmus test, Johnson said.

He cited the proposed mosque near ground zero in New York as a possible cause du jour for privacy advocates.

“That’s a fine civil liberties stance, but you’re going to piss off a lot of people,” Johnson said, noting Republican criticism of the controversial project when it touched off a national firestorm in the summer of 2010.

In one of the more public airings of the Muslim community center, Iowa Rep. Peter King said in a Fox News interview that “it is very offensive and wrong” for a mosque to be “within walking distance of where so many Americans were killed by radical Muslims.”

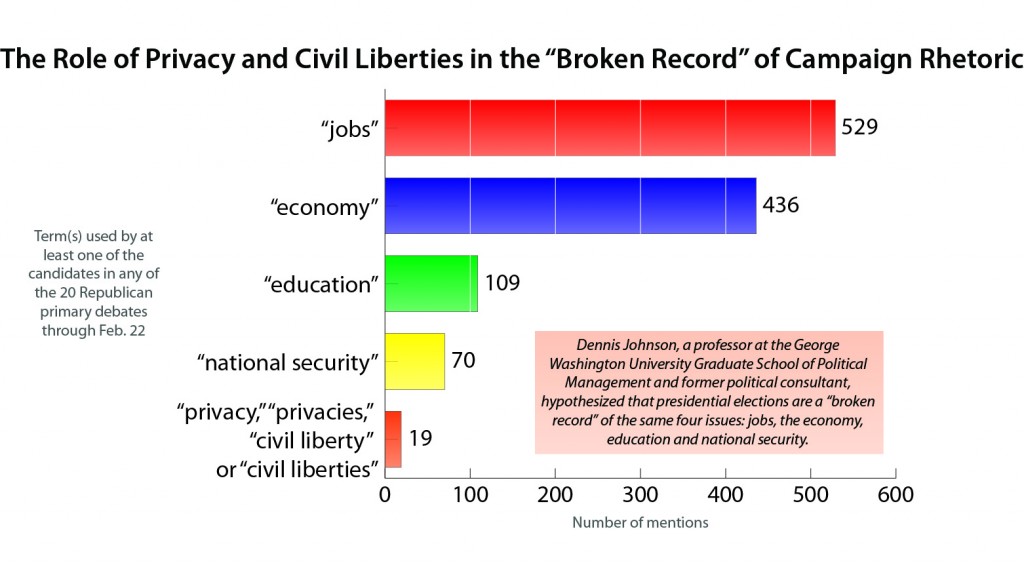

Johnson and Harper agreed those candidates who do broach the topic of privacy risk being crowded out by what Johnson called the “broken record” of campaign talking points: the economy, jobs, education and national security.

“The big, big issues are usually related directly to money…” Harper said. “You’re talking about billions and hundreds of billions of dollars moving around. Those are political issues — those are hot-button issues.”

Tell that to Christian Rice, a sophomore at Georgetown University who heads the school’s Youth for Ron Paul chapter.

He called civil liberties the “most important issue of the campaign right now” — not the economy, as many polls have indicated since last fall.

Unlike the famous federal debt clock hovering over Sixth Avenue in New York, liberty is not an easy quality to conceptualize, Rice said.

“You can’t put a number on it,” he continued. “You can’t see how much is being devalued.”

A history of silence

So when was the last time civil liberties played even a peripheral role in a presidential election?

“No, not a single one,” said Michael Cornfield, who teaches alongside Johnson. “Not even a primary.”

Johnson went back to the 1950s, when he said the Red Scare led to an upsurge in privacy concerns as the federal government investigated citizens for alleged Communist ties. But after McCarthyism, civil liberties issues stopped reaching a national audience, let alone the transcripts of stump speeches, he added.

Cornfield explained that in modern times, privacy has been repackaged by politicians as in conflict with national security. He credited blockbuster television shows like “24” with skewing Americans’ perceptions of civil liberties, turning them into flexible rights that can be set aside for heroic patriotism.

“For better or for worse, civil liberties generally come up in counterpoint to national security,” Cornfield said. “Most candidates believe in most polls, and most polls support that belief that most Americans will support national security over civil liberties in overwhelming majorities.”

Cornfield’s theory is up for debate.

In the Pew Research Center survey on the generation gap, 54 percent of respondents agreed that it is unnecessary to give up their civil liberties to curb terrorism. The margin widened to 72 percent to 25 percent when the same question was asked of Millennials, which the center has previously defined as anyone born after 1980.

Rice, a Millennial by the Pew measure, predicted privacy is likely to remain a back-burner issue, something he described as “just an effect of what the voters want to hear.”

He suggested two scenarios in which civil liberties could be thrust to the forefront of political debate. Either major corporations will have to jump in the political discussion like they did with the Stop Online Privacy Act or “something tangible” will have to be involved in an intrusion of privacy, such as large amounts of land or money, Rice said.

Yet Rice sided with ex-consultant Johnson when it came to what direction he would offer a presidential hopeful on privacy issues.

“If their no.1 goal is to win,” Rice admitted, “I would tell them not to talk about civil liberties.”