Well into a summer of shelling, street fighting and sniper fire, several of the scores of correspondents covering the Israeli siege of Beirut in 1982 would joke, a bit wistfully, about the “courage not to file.”

That summer was long and, despite the Mediterranean breezes, the air was steamy and fear prevailed one day to the next. Fighting between the Palestine Liberation Organization and the Israelis surrounding the western half of the city was sporadic and intense, and from early June to the end of August stories of the destruction and urban warfare dominated front pages around the world.

Writing about military conflict has its dangers, of course, but adrenaline-infused reporting also carries a strange excitement. Some reporters and photographers become known as “war junkies” because they often move from covering one conflict to another. For many, a quote attributed to a young Winston Churchill describes the experience nicely: “Nothing is as exhilarating as to be shot at without result.”

Reporters recorded the events but soon recognized that even accounts of bombings and shooting can sound the same or only marginally different from the day before. Beyond recording the incremental news, the latest outrage or attempts to create a cease-fire, journalists became hungry for sidebars, those intriguing stories that personalize the conflict or explore a quirky consequence.

One day, for instance, I was delighted to interview a tall and elegant French prostitute who retired to Beirut to open a tiny, checked-tablecloth restaurant. “You must tell me when to leave,” she said rather plaintively as I sat down with two other reporters for lunch. It was a week or so into the conflict and the Israeli Defense Force had dropped notices over the city telling civilians to leave and detailed a number of safe passage streets they could use in the next day or two. Everyone believed that street-to-street fighting was inevitable and would be vicious.

I suggested to the retired and anxious woman that if she was afraid for her life, she should get out immediately. No, that wasn’t the concern, dying is easy, she replied, her worry was being disfigured.

A week or so later, I walked past the shuttered café and learned that she finally had left, after gunmen aiming to settle a private score with others had burst into the restaurant. In the exchange of gunfire, they shot her pizza oven, fatally.

Such stories, though ephemeral, gave readers a taste of life and the people in a besieged city. They also gave reporters a chance to of get away from the daily grind, the “feeding the beast” mindset of so much journalism that we practiced then and even more now in the era of a 24/7 news cycle.

In the face of a relentless hunger to deliver more copy, several of us would sit over drinks in the bar off the lobby of the old Commodore Hotel and fantasize about writing more meaningful accounts, articles with what we believed would be appropriate depth and passion. Though our stories had drama, after awhile we considered them routine; we wanted the time and freedom—and space–to ignore the daily report and concentrate on more complex truths. In other words, we wanted to write what we now call long-form narratives.The death of an old friend and colleague a few months ago reminded me not only of my own mortality and of such primitive tools of journalism, but his passing also brought back memories of that odd longing for the “courage not to file.”

Richard Ben Cramer, the friend who won a Pulitzer for his coverage of Middle East conflict and went on to win accolades for his extraordinary book What It Takes, about the 1988 presidential campaign, exemplified the admonition that arose in the heat of reporting so many scores, hundreds of relatively easy front-page stories.

Cramer understood what it takes to have that courage, and he was supported by the legendary Gene Roberts, then executive editor of the Philadelphia Inquirer, but who worked before and after at The New York Times.

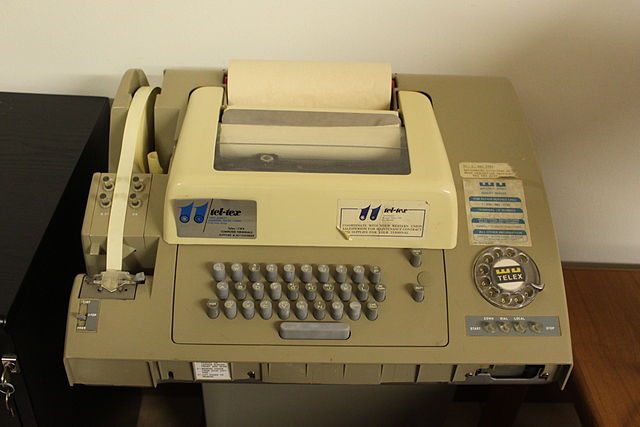

A Telex machine. (SOURCE: Wikipedia)

The PLO had agreed to a cease-fire and accepted international offers to evacuate their fighters onto freighters and with their safe passage guaranteed, to sail into exile in Tunisia. Other events were yet to come in that tumultuous time, the massacre at the Sabra and Shatilla refugee camps by Christian militias was not long away; the following year, the American embassy in Beirut would be destroyed by a bomb; and later, a suicide bomber would drive his truck through the gates of a U.S. Marines compound at the Beirut airport, killing 241 servicemen. Yasser Arafat would return to Lebanon once again, but this time further north in the town of Tripoli, to fight and flee from a Syrian-backed force.

But this day was the denouement of the deadly summer-long fight, and almost every journalist in the city was focused on seeing and recording the climatic departure of PLO fighters from the port. The news would be atop every front page in the U.S., Europe and throughout the Middle East and Africa.

I saw Richard in the lobby and invited him to join me on a ride out to the port. “Naw,” he replied. “I think I’ll give it a pass today.”

He and his editor had decided to use the wire service reports, allowing Richard to concentrate on finishing the long piece he had been working on: the life of raggedy but disciplined Palestinian fighters and their street fighting ways against a powerful, indeed overwhelming, army.

To devote that day to writing his narrative and to ignore the surefire front-page story of the climax of a three-month war was simply astounding to me. Scores of other reporters were conscientious, hardworking and all the rest; Richard’s (and his editor’s) belief was that it was more important to give readers a well-reported and fascinating read into the minds and actions of these young fighters.

The attitude was audacious and exemplified ever after for me what the “courage not to file” really meant. So much of that summer and the years before and after were absorbed in daily, dutiful stories. Perhaps even more than my fair share appeared on the front page, but so many of them are not memorable, not really worth the time and attention I gave to them. As Frank Sinatra sang, “Regrets, I’ve had a few. . .” and this was one that I never fail to mention.

Richard showed the same confidence and courage in more peaceful circumstances as he wrote about outsize sports figures such as Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams. But his major work began in 1988 as we followed presidential candidates around the country.

He knew his book exploring the background and emotional motivations behind each candidate wouldn’t come out for at least a year or even longer. Actually it appeared four years later, in time for the 1992 election. But he believed it was essential as a good journalist to tell a more developed and important story about what it takes for a candidate to believe he should be the president. For many, Cramer’s book is a classic of political reporting, outliving dozens of campaign books before and since. Twenty years after Cramer’s book came out, a young reporter at the Medill school at Northwestern asked me about the best political book I ever read. I told him, “What It Takes.”

When Richard died earlier this year, there were many tributes to him and his craft. Among them, this Washington Post blog, his obituary in The New York Times, and a Daily Beast appreciation.

There are many fine examples of the type of literary journalism practiced by Richard and those who preceded him as far back at John Hersey and even Stephen Crane. Their ranks include contemporary writers from the New Yorker’s John McPhee, Susan Orlean and, more recently, Katherine Boo.

But most of contemporary journalism, or what passes for it, is focused on shorter, quick-hit, daily, perhaps hourly updates. These stories are not memorable nor are they meant to be. They address a hunger for the latest information; they feed the beast not in large, satisfying meals but in spoons full of fact or, worse, just attitude.

I don’t mean to crank that daily reporting is not worthwhile; it is the lifeblood of good journalism. How else would we keep track of political shenanigans and corruption; how many organizations would send observers to sit in courtrooms and take note of justice denied; how many would devote the time and expense required to expose the operations of shady businesses?

But what I learned from Richard and others who had the “courage not to file” was that so much of what passes for reporting is not worth your time. I learned that it is better to follow your instincts when you come across a good story that demands your attention and takes serious effort. These stories won’t all win Pulitzer Prizes, or become best-selling books or be transformed into successful screenplays.

What they will do, however, is give you stories for years to come, and memories of how you spent a life of reporting.

Tim McNulty is co-director of the Medill National Security Journalism Imitative and a lecturer at Northwestern University’s Medill School. He was a longtime foreign correspondent and senior editor at the Chicago Tribune. He helped direct the newspaper’s coverage of the September 11 tragedy, the American strike into Afghanistan and the invasion of Iraq.