One of the reasons former NSA contractor Edward Snowden was able to get away with stealing top-secret documents about government surveillance programs is because Washington’s system of classifying national security information is badly broken. So many entire categories of data are classified—from how surveillance programs like PRISM work to the altitude at which US warplanes fly—that an astounding 4.9 million people are required to have “Top Secret” clearances just to do their jobs as government officials or, like Snowden, as private-sector contractors working on defense and intelligence matters. The system of vetting these people for clearances is dysfunctional, and national-security experts like former House intelligence committee chairwoman Jane Harman have said recently that the Snowden case is a good example of that.

But the problems extend far beyond who gets security clearances. So says the latest annual report (pdf), published June 20, by the Information Security Oversight Office, whose job is to get agencies to classify fewer documents and to declassify many more of them while making sure that real secrets stay secret.

The ISOO estimates that the government and its contractors spent $11 billion last year on “security classification activities”—plus an estimated 20% more for the CIA, NSA and other agencies whose activities are too secret to even mention in the report. The good news is that this is 13%, or $1.7 billion, less than the year before.

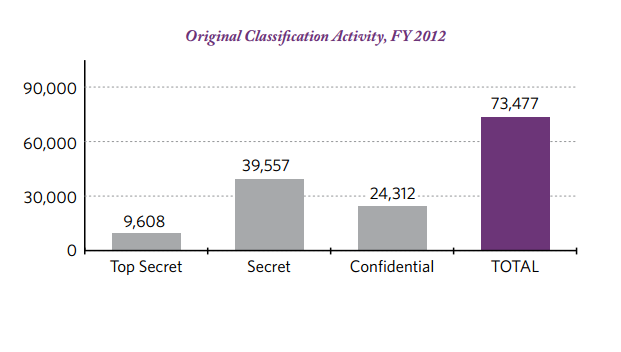

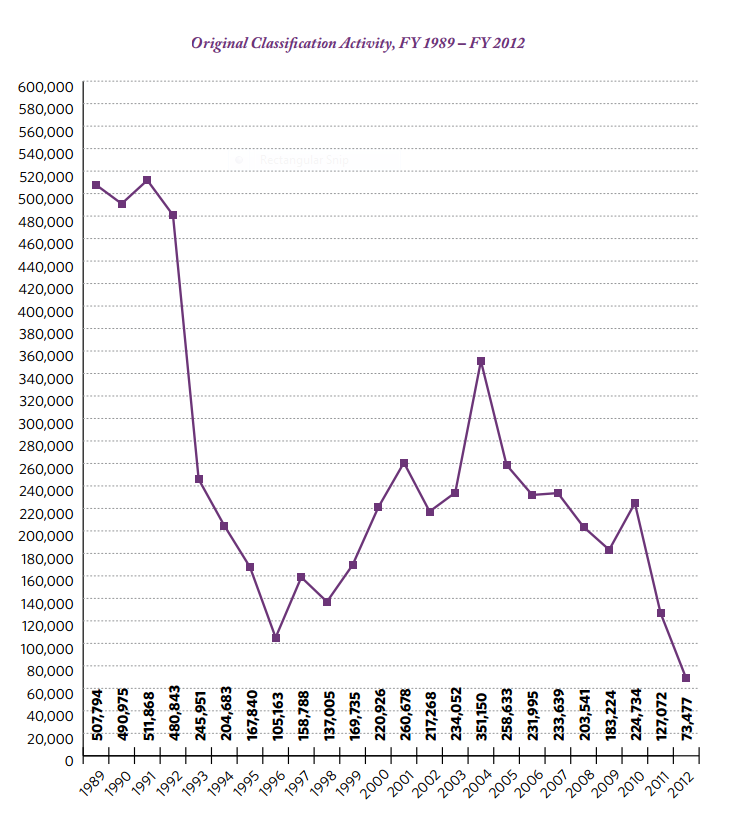

But there’s a more important statistic. The report attributes the lower cost, in part, to a project launched by the Obama administration called the Fundamental Classification Guidance Review (FCGR), which pressures officials to set a higher bar for making things secret. Last year, the report said, US agencies reported 73,477 “original classification decisions” (i.e., the decision to classify something, and at what level)—a drop of 42% from the previous year.

Here’s the breakdown:

And if that seems like a lot, look at how much it has come down, especially since Barack Obama took office:

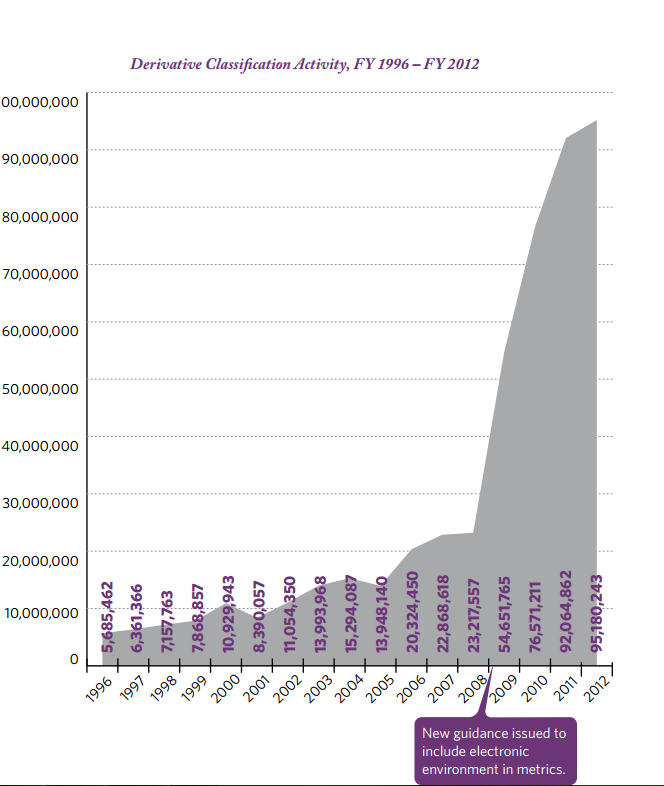

The report isn’t all good news. Overall, it says the government continues to generate classified information at historically high levels, especially through derivative classification, which means putting already classified information in a new document.

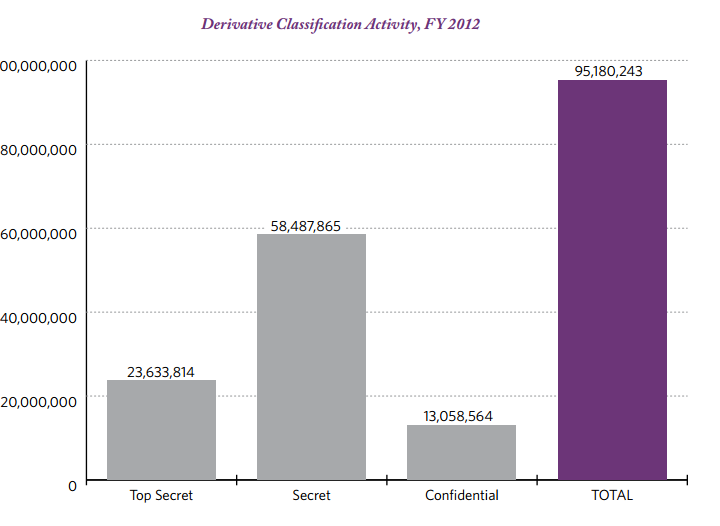

Here’s a breakdown of that:

And a historical breakdown, showing the huge jump when electronic documents were included:

Steven Aftergood, who heads the Project on Government Secrecy for the Federation of American Scientists, told Quartz that there’s a direct correlation between all of the over-classification cited in the report and the government’s inability to stop people like Snowden from stealing information. “The more secrets we have, the worse job we do in preserving them,” he says. But he says the 42% drop in the creation of “new secrets” is a glimmer of hope because it appears to be the result of a concerted effort that includes several Obama administration initiatives. “People are saying, ‘Wait a minute, do we need to classify this?’ in a way they had not been before,” Aftergood says. “It is a modest but hopeful sign, potentially a turning point in overall secrecy reduction.”

One thing the new report doesn’t do, though: Describe what kinds of information—the 42%—are no longer considered secret.

Josh Meyer is director of education and outreach for the Medill National Security Journalism Initiative. He spent 20 years with the Los Angeles Times before joining Medill, where he is also the McCormick Lecturer in National Security Studies. Josh is the co-author of the 2012 best-seller “The Hunt For KSM; Inside the Pursuit and Takedown of the Real 9/11 Mastermind, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed,’’ and a member of the board of directors of Investigative Reporters and Editors.