Posted Sept. 9, 2013

How much can you discover about your own life by tracking just the destination of your phone calls, texts and e-mails?

National Security Agency officials, as revelations of their surveillance programs continue, insist they are not interested in the actual content of the millions of communications they track. In the past several weeks, however, they have admitted collecting email messages of Americans by the tens of thousands.

The continuing revelations piqued my curiosity about what some company or government agency might learn in even the most casual collection of daily personal communications.

I asked seven graduate students to record the destination and number of their calls and online contacts during a two-day period in early July. I chose the dates at random and in the past so they could look up their own records of online banking, credit card purchases, social media posts, websites and cell phones. Their telephone calls, of course, were almost entirely by cell phone and the called numbers were easy to discover. The GPS tracker embedded in most modern cellphones and nearest cellphone towers that record every signal help pinpoint the caller’s location.

Following the NSA rationale, the students’ goal wasn’t to establish who they called or texted or even the content of their conversations. The idea was simply to “connect the dots,” the phrase intelligence officials have used since 9/11 to justify the secret surveillance programs.

I asked the students not to identify their contacts’ names, just call them “subject one” or “person one.” So, for instance, I don’t know but I could make my own assumption about the student who texted “person three” 17 times one day and 12 times the next day, interspersed with several phone calls to that person each day.

However, I may be wrong.

The students also took note of electronic contacts that could be viewed by a third party and thus considered “public.” Their credit card information, for example, is readily accessed by a credit reporting agency and that private company routinely shares it with retailers and banks. When and where they used a transit pass is available to local government transit and police agencies, and the movies they viewed on Netflix or the books on their Kindle or Nook are accessible.

In the online world we have become used to Google’s all-seeing eye overseeing what we search for and the messages we send. We tacitly accept that Amazon will use its algorithms to determine our likes and dislikes on books, music, clothing and kitchen appliances. We readily trade privacy for convenience. We even acknowledge that advertisers target us because of our previous purchases and even references in our mail. Basically, we rely on these electronic contacts for the stuff of our daily life.

One student made a concise accounting of her communications:

“During the days of Tuesday, July 2nd and Wednesday, July 3rd I engaged in 25 texts, 35 emails and 21 calls. In addition, I submitted my insurance card to Walgreens for a prescription, took two trips to gas stations where I used my credit card to get gas, used my I-Pass six times on the tollway and completed one ATM transaction to get cash.

Moreover, I used Google maps three times to get directions, used my fitness app to record my physical fitness activities and ordered takeout over the phone using my credit card. Lastly, I engaged in several social activities online including 2 Facebook posts, uploaded three photos online and visited 51 websites.”

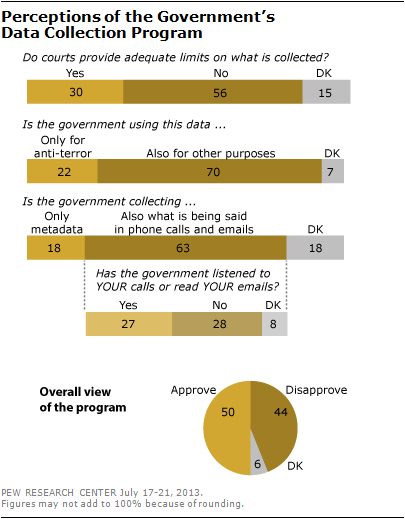

“A majority of Americans – 56% – say that federal courts fail to provide adequate limits on the telephone and internet data the government is collecting as part of its anti-terrorism efforts. An evenPerceptions of the Governments Data Collection Program larger percentage (70%) believes that the government uses this data for purposes other than investigating terrorism.” (Pew Research Center)

Prior to the Fourth of July holiday, several made travel arrangements. A few students used their CTA passes while another bought an airline ticket online and signed up for the air carrier’s credit card, providing a great deal of personal information.

On the first day, he made five calls to a Canadian telephone number using a Magic Jack application on his smartphone. He called Canada again three times the next day, calls to or from foreign countries that presumably were collected by NSA supercomputers.

Undoubtedly, so was the video call on Skype that another student made to her family in Pakistan.

As with most of us, we go through the day barely conscious of how much personal data we trail along our electronic contacts. Another student recalled her typical day begins with checking e-mail and Facebook and Twitter. She uses a charge card for coffee at Starbucks and for all her meals away from home.

Students often are on the move, literally. One changed apartments during this period and as soon as she had wireless access, she was on her iPad, calling, browsing and checking e-mails. “I called Subject 2 on Viber, which is an online free app for calls and messages. I texted Subject 4 on the iPhone and we exchanged 5 messages.” She also has an application on her phone that records every step she makes.

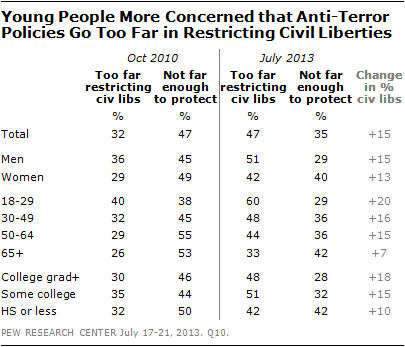

“Those under the age of 30 stand out for their broad concern over civil liberties. By about two-to-one (60%-29%) young people say their bigger concern about the government’s anti-terYoung People More Concerned that Anti-Terror Policies Go Too Far in Restricting Civil Libertiesrorism policies is that they have gone too far in restricting the average person’s civil liberties rather than not going far enough to protect the country.” (Pew Research Center)

The use of social media appears to increase the younger the generation. Besides checking email and text throughout the day, one student reported posting Instagram photos, as well as “liking” many of her friends’ pictures and posts.

She used an application called Vine that allows her to post six-second videos for friends to share. Because Vine is fairly new, many friends have never bothered to make their images private. “I think we should take added precautions when using Vine because it incorporates text, location and video,” the student said. “With video, you can actually see where you and your friends are. I don’t know about you, but video just adds an extra level of creepiness versus pictures.”

Government officials contend they are not interested in the vast majority of citizens and that laws and safeguards are already in place to protect the innocent from government snooping. But if there were intrusions by some person or agency, they would find the numbers to reveal that this student shopped at Macy’s and had access to a bank reference number because she deposited a check online. She also browsed Craigslist, shopped at Trader Joe’s and used her credit card to buy flowers at one store and clothing at Express.

Another student signed up for an e-newsletter from the Bureau of Labor Statistics for a reporting class. She wasn’t going to account for that but then realized she already has between 20 and 25 newsletter subscriptions and many organizations have her information.

We are so used to tracking and being tracked only one student mentioned using her Northwestern University “Wildcard” to borrow books from the library. She recalled that when mailing a package, she received a tracking number along with the receipt. Later she picked up medications at CVS and verified her insurance number, then booked a flight and used her award miles to pay for it.

The same student sent and received at least 10 emails from her NU account to story sources, five emails to family from her Gmail account and one to a company to get a replacement for a product.

“I watch a lot of shows on Hulu, and even though I don’t have a Hulu account, it tracks which shows I watch and where I stopped watching on each show. The same goes for YouTube; although I don’t have an account, there are still advertisements and suggested shows.”

She found targeted advertising most irritating. In one graduate class she reported on elderly issues and researched many topics dealing with seniors. She said the advertisements she began receiving were for Alzheimer’s disease and dementia information, senior care homes, and other elderly issues. “My mom told me that I received an application in the mail to join AARP. My parents have been retired for years, but the application was addressed to me, not them.”

The impact of knowing your calls, texts and emails are collected can be more ominous, however.

“If some sort of surveillance entity (government or otherwise) got hold of my electronic information for last Tuesday and Wednesday, it’s a little surprising how much they would know about my life – from smaller details (what neighborhood I live in in Chicago) to larger themes (what sort of issues I’m interested in, politically, and what medications I take).” She also said it would also be obvious from a web inquiry that she was planning a move to Washington and could also determine that she has a strong personal connection to downstate Illinois.

Upon reflection, one student balked at sending her own collected totals to me in an email message. While another described most of her “trackings” as mundane and uneventful, she said she felt very protective of her work with the Medill Justice Project, which looks into possibly wrongful convictions. She said her communications with fellow students and possibly witnesses demands an “extra layer of protection from government inquiry.”

Another student has set up her computer so that her web history doesn’t save overnight. Or does it?

[field name=”tim-tagline”]