An Afghan soldier, second from left, and U.S. Marines respond to an explosion inside a mock Afghan village during a training exercise on Sept. 23, 2008, at the Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center in Twentynine Palms, Calif. The U.S. Marine Corps recently licensed another 300 square miles at Twentynine Palms from the Bureau of Land Management.

TWENTYNINE PALMS, Calif. — The Twentynine Palms Air Ground Combat Center is a 1,100-square-mile training facility for U.S. Marines where infantry units hurl grenades, aircraft drop bombs and artillery batteries pummel the earth with 100-pound shells.

But buried beneath the ground in this large swath of California’s Mojave Desert are brittle pieces of stone technology dating back 12,000 years.

So before Marines can start training, Defense Department archaeologists have to ensure that the cache of prehistoric Native American artifacts scattered about are surveyed, catalogued and collected. The Marines recently licensed another 300 square miles from the Bureau of Land Management, and the archeologists already are on the ground there.

“We have more than 2,000 sites on the base,” said John Hale, one of the three full-time archaeologists who work at Twentynine Palms, “and we’ve only surveyed about 50 percent of it.”

Hale’s team has completed the initial phase of archaeological assessment for the new acquisition, which involves systematically walking around the land and noting areas of interest and possible past habitation. But the real work begins once sites have been singled out for excavation.

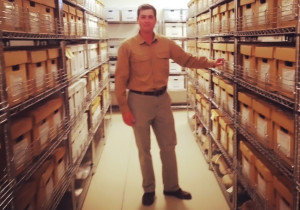

John Hale is one of three full-time archaeologists who work at Twentynine Palms. (Tobias Burns/MEDILL)

“We’re looking for areas that have a potential subsurface component,” said Leslie Glover, another of the base’s archaeologists. “When you start to see relationships between objects over horizontal distances, that’s when things really get interesting.” For example, if scientists find stone shavings in one spot and burnt seeds nearby, they begin to see the patterns of a rudimentary economy.

But discerning these kinds of ancient geographical relationships takes time, and work can continue on a dig site for months and sometimes years. Given that the Marine Corps has been fighting for usage rights to the BLM-managed land for almost a decade, this is time the military says it does not have.

“We need the land for brigade-level training, which is essential,” said Capt. Justin Smith, a public affairs officer at Twentynine Palms. “This is the first time the base is going to be able to do live fire exercises on such a large scale, with 15,000 Marines and sailors working together.”

The military archeologists’ first responsibility is to accommodate the training needs of the Marines, but it’s only part of the job. “The other 50 percent comes from our own evaluations of what has to get done from a cultural perspective,” Smith said.

After the excavations are completed, the team members begin what they call the mitigation phase of their work, looking at the potential impact of various activities on or near the site, moving targets and cordoning off sensitive locations.

“We put a lot of things in boxes and prep them for display,” said Charlene Keck, collections manager for the department. “That’s often the best thing we can do to preserve the heritage here.”

The preservation sites at Twentynine Palms are numerous enough to fill an on-base museum full of projectile points, milling slabs and rock art panels, some types of which are unique to the region. There are two main display areas, rooms for examination and a storage facility packed to the brim with artifacts.

An on-base museum at Twentynine Palms features projectile sites and milling slabs. (Tobias Burns/MEDILL)

The artifacts are thought to be mostly Serrano, one of the indigenous peoples of California, but other migratory populations are likely represented as well.

At one site on the base, Dead Man Lake, charred bits of ancient mesquite pods have been found, as well as pictographs and rock drawings as old as 10,000 years.

The base also has more-recent archaeological evidence to consider and collect. Much of it relates to early American homesteading and mining operations. There are old American military roads and airstrips, as well.

But the heart of the archaeology office at Twentynine Palms lies in the prehistoric past. “I have a particular fondness for some of the oldest artifacts,” Glover said, referencing some domed scraping tools used by the Serrano. “I have the incredibly scientific view that they’re really, really cool.”