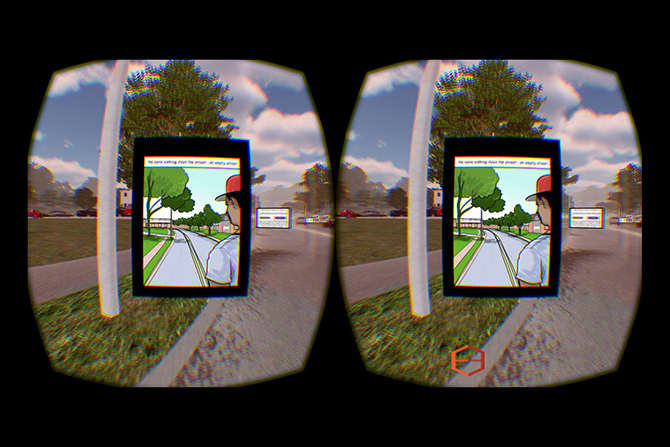

This image is a screenshot from Dan Archer’s Ferguson Firsthand piece. (Dan Archer/Courtesy)

In the course of covering national security, there may be moments when words will seemingly come up short — scenes where descriptions rooted in paper and ink (or in pixels on a screen) will feel insufficient to put readers in the depth of a moment.

The color of the clouds created by smoke and gas suspended in the air during a riot. The timbre of a witness’ cries after a shooting. The claustrophobia of a crowded courtroom.

The pressure to capture the multi-sensory essence of a story might be a challenge for print reporters, but moments like these are the stuff one journalist’s reporting dreams are made on.

Dan Archer.

Archer is a transmedia journalist who works as a Reynold’s Fellow at the Missouri School of Journalism’s Donald W. Reynolds Journalism Institute and a graphic journalist at Empathetic Media.

His style of domestic civil rights and national security reportage combines elements such as video game platforms, comic-book-style editorial cartooning, data and other media elements into what he calls “immersive journalism” to give audiences greater control of how they navigate the news and to let them explore stories from multiple points of view.

One such endeavor is a comic recreation of eyewitness testimonies from the Michael Brown shooting in Ferguson, Missouri, created for Fusion. The Instagram image below is a snapshot from the project, which can be viewed here.

Another was his so-called “sketchbook” from the streets of Baltimore’s Sandtown neighborhood, where Freddie Gray was arrested and later died in Baltimore Police custody.

A sketchbook from the streets of Baltimore: http://t.co/DsBUdDzfRO via @FusionComics pic.twitter.com/xiQMwCYwIk — Fusion (@ThisIsFusion) May 19, 2015

But perhaps his most well-known project — and one which, according to Archer, most accurately reflects his current focus on transmedia (versus merely graphic) journalism — was the “virtual-reality experience” he built which allows users to explore the Michael Brown shooting crime scene from the perspectives of multiple witnesses and incorporates primary documents, witness testimony, photo-based scene reconstruction, data visualization and more.

The Medill National Security Journalism Initiative spoke to Archer via Skype to get the story behind his stories and insight into the potential for new media to change the face of national security reporting.

According to Archer, the graphic side of transmedia reporting can catch people off guard initially, but actually allows for greater ease of access to subjects — especially ones who might otherwise be scared off by cameras.

He also said it helps keep the stories focused on their subjects, rather than on the journalist’s experience while trying to report them out (i.e. riot coverage that focuses on what’s happening to a reporter vs. what’s motivating the crowd to be there in the first place). He expressed a discomfort with this “ego journalism,” but was careful to call out the practice vs. its media practitioners.

But he said that transmedia journalism does little to make government and law-enforcement officials more comfortable in interviews and depictions than more traditional forms of reporting would, especially in the age of body cameras and a growing demand for increased police accountability.

Archer said that immersive reporting isn’t that big of a departure from graphic journalism. Rather, it allows aspects of 2-D reporting to be expanded into further dimensions (such as sound or, in the case of versions of his Ferguson reconstruction designed for virtual-reality consoles, three-dimensional navigation and spatial understanding).

He said diving into the design of such storytelling environments isn’t intensely complicated due to the availability of game engines (some of which are freely available) and YouTube tutorials.

His advice for more traditional print journalists?

Throw orthodoxy out the window, get a handle on emerging interactive story tools and set out to discover fresh approaches to building narratives — especially when it comes to topics that may be so ubiquitous that audiences have tuned out their media coverage.