WASHINGTON – The Islamic State, also known as IS, is working to carve out a caliphate in Iraq and Syria, or an Islamic state led by a religious leader.

According to an article on vox.com, IS split from al-Qaida in early February of this year. Now, looking back at the way IS was able to gain strength in Iraq, it is easy to see where America’s counterterrorism strategy only gave IS an opportunity to expand. An article from The Hill says Sen. James Inhofe (R-Okla.), a ranking member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, pointed out how President Obama’s inaction in Syria led to further gains by ISIS in Iraq. His comments came just before reports of ISIS gaining control of a major military base in Syria, The Hill reported.

Washington’s failure to intervene in the humanitarian crisis in Syria under President Bashar al-Assad’s regime created a destabilized area, a perfect breeding ground for IS to gain support.

Peter Knoope, director of the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism in the Hague, Netherlands, explained that using non-violent counterterrorism tactics can actually be more beneficial than the way the U.S. looks to diminish the strength of terrorist groups. The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, which is funded through the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs and a partnership of three institutions, focuses on preventing and countering violent extremism.

“Trying to understand why people feel attracted to violent extremist narratives and violent political action is an important strategic approach to counterterrorism,” Knoope said.

He explained that preventing the organization from gaining new members can reduce the size of the organization.

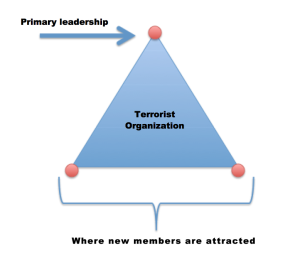

Knoope, a career diplomat who was posted as the head of mission to Afghanistan, said terrorist organizations can be looked at as a triangle, with the tip of the triangle being the main leadership. The “baseline” is where new people join, and by focusing counterterrorism efforts on understanding why young people join terrorist organizations, Knoope said, you can effectively shrink the triangle.

For example, the death of Osama bin-Laden in 2011 did not lead to the end of al-Qaida. Instead, it only provided the opportunity for a top deputy, Ayman al-Zawahiri, to rise up and take his place.

“In some cases decapitation of the triangle will only bring new leadership that is more aggressive, more military focused and more violent focused than the former leadership,” Knoope said.

He explained that we can see something similar happening in Nigeria with the Islamic group, Boko Haram. The death of leader, Mohammed Yusuf, only led to the rise of his more aggressive counterpart, Abubakar Shekau. With Shekau’s leadership, more Nigerians have been attracted to the organization.

IS growth in Iraq

In his book, “Globalization & Terrorism: The Migration of Dreams and Nightmares,” Jamal Nassar explained terrorism is often a reaction to injustice. Nassar, a political science professor at Illinois State University and authority on the Middle East, further explained that, “the terrorist often feels deprived of some rights or maltreated…”

Iraq was controlled on and off by a Sunni regime until Saddam Hussein’s government fell in 2003. In 2006, Nouri al-Maliki was appointed as prime minister – meaning a formerly Sunni-led state transitioned to a Shiite-led state.

A 2011 Pew Research poll found 51 percent of Iraqi Muslims identify as Shia and 42 percent identify as Sunni.

The transition left many Sunnis dissatisfied with the central government in Baghdad. In June, Iraqi pollster, Munqith al-Dagher, said IS is benefiting from Sunni dissatisfaction because they see the government depriving them of their rights and aligning too closely with the Shia-led state of Iran.

This goes along with Knoope’s explanation of why people join terrorist groups:

• Feeling like an outsider

• Being unaccepted in their environment

• A collective search for identity

• Lack of political influence

“Somebody comes along and tells that person you can be a somebody and have an important impact on a very important environment,” by joining a terrorist group, Knoope said.

Non-violent counter terrorism strategies, Knoope said, begin with knowing what’s going on in the community and who’s framing the dialogue to attract new members in religious or political terms.

From there, states can respond by helping to offer solutions for meeting those needs.