WASHINGTON – My mother and I came to Hong Kong – then a British colony – in 1991, and when I was little, sometimes she would tell me about my first and only personal encounter with an intelligence agency.

When we first entered Hong Kong, my mother and I were led into a room near the border checkpoint by an operative of the Special Branch of the Royal Hong Kong Police, then a front office for MI5, the feared British police and intelligence agency.

“What is your business in Hong Kong?” the agent asked.

It turns out my grandfather was an intelligence officer of the Chinese Communist Party posted as a school principal in Hong Kong in the 1940s, and the Special Branch had been watching him the whole time.

Luckily my mother and I walked out of the room that day, and I continued to be a normal kid growing up in Hong Kong.

But it was after I became a journalist in Hong Kong that I realized how this Asian financial hub is also the spy hub of the Far East. And despite the fact that Hong Kong has been under Chinese rule since 1997, its law enforcement agencies still have close contact with U.S. and British law enforcement and intelligence agencies.

“What is your business in Hong Kong?” the agent asked.

It turns out my grandfather was an intelligence officer of the Chinese Communist Party posted as a school principal in Hong Kong in the 1940s, and the Special Branch had been watching him the whole time.

Luckily my mother and I walked out of the room that day, and I continued to be a normal kid growing up in Hong Kong.

But it was after I became a journalist in Hong Kong that I realized how this Asian financial hub is also the “spy hub of the Far East.” And despite the fact that Hong Kong has been under Chinese rule since 1997, its law enforcement agencies still have close contact with U.S. and British law enforcement and intelligence agencies.

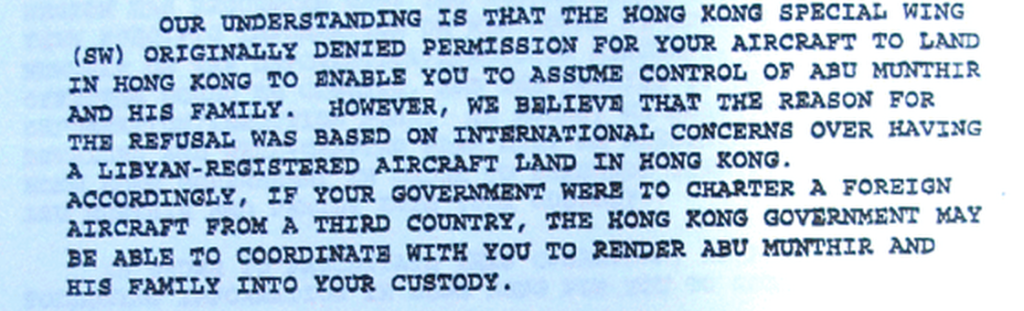

According to the Guardian and the South China Morning Post, in 2004 Sami al-Saadi, a vocal opponent of late Libya dictator Muammar Gaddafi also known as Abu Munthir, was detained in the Hong Kong International Airport for a week before forced onto a flight to Tripoli. After the fall of Gaddafi’s regime, Human Rights Watch obtained fax correspondence between CIA and Tripoli, which revealed Hong Kong government’s role in al-Saadi’s rendition to Libya.

This CIA fax to Libya authority shows the Hong Kong Government offering advices to ensure the rendition of al-Saadi. (Screenshot of documents released by The Guardian via DocumentCloud at http://www.theguardian.com/world/interactive/2011/sep/09/libya#document/p6)

The fax shows that the Hong Kong government offered suggestions to Libyan authority on how to assume control of al-Saadi.

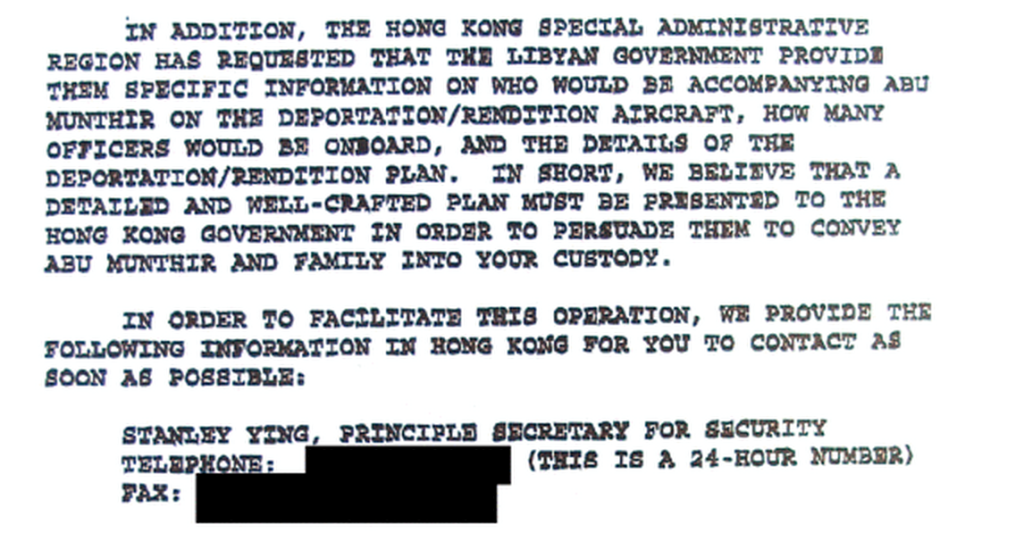

The segment of the fax shows the Hong Kong Government requesting the details about the purposed rendition of al-Saadi. (Screenshot of documents released by The Guardian via DocumentCloud at http://www.theguardian.com/world/interactive/2011/sep/09/libya#document/p6)

It also shows Stanley Ying, the then Principle Secretary for Security, is listed as a key contact in the Hong Kong government.

But that does not mean the Hong Kong government is always an ally for Western governments. In the case of Edward Snowden, we saw the opposite.

Edward Snowden came to Hong Kong on May 20, 2013 from Hawaii, and he seemed to have faith in Hong Kong’s judicial system.

“Hong Kong has a strong tradition of free speech. People think China, Great Firewall … but the people of Hong Kong have a long tradition of protesting on the streets, making their views known … and I believe the Hong Kong government is actually independent in relation to a lot of other leading Western governments.”

— Edward Snowden

Despite numerous protests from the U.S. government, the Hong Kong government allowed Snowden to fly to Moscow.

From Snowden’s case, we can see that the decision of whether to hand over a valuable person to Western intelligence really depends on what kind of information that particular person possesses.

Ben Lam, a local news editor who was assigned to cover Snowden’s case and has numerous encounters with Chinese intelligence in Mainland China, said Hong Kong becomes a hub for intelligence activities because of historical and geographical reasons.

“Back in the days of British rule, it was the West’s window to Mainland China and vice versa for the Chinese,” he said.

“I would say the major players in Hong Kong right now are the MI6, CIA and also Chinese intelligence agencies,” he said. “The Japanese government also has an extensive intelligence network in Hong Kong, and their operatives often use journalists as their covers.”

Hong Kong is a city known for its financial activities, tourism and political tension between locals and the Chinese government. But it is also a place where an invisible war on national interests happen everyday.