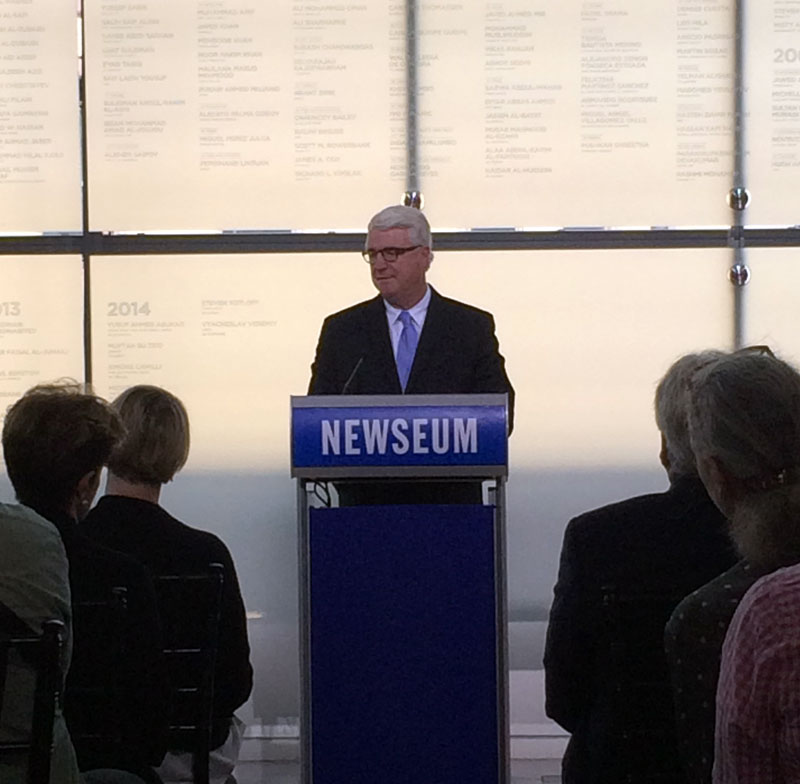

WASHINGTON – Faced with an upsurge in journalist kidnappings, President Barack Obama issued a new executive order in June that allows families to offer ransom money without fear of prosecution and establishes an interagency fusion cell to improve U.S. hostage recovery efforts.

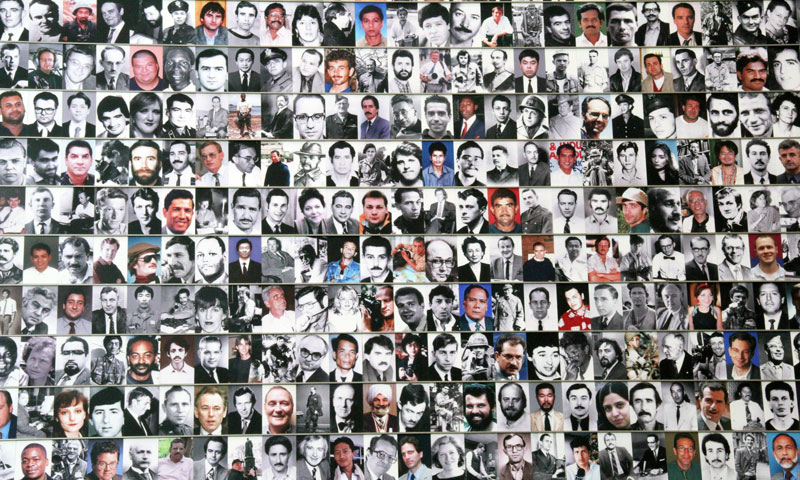

Kidnappings of journalists are on the rise, up 35 percent in 2014 to 119 journalists, according to Reporters Without Borders’ most recent annual roundup of abuses against journalists. RWB also reported that 66 journalists were slain in 2014, bringing the number of journalists killed in connection with their work in the past 10 years to 720.

But how far do the changes go toward providing an effective solution to the bureaucratic tangle we’ve already spun when it comes to coordinating the return of kidnapped Americans?

The fusion cell is led by senior FBI official Michael McGarrity and housed at bureau headquarters. It is made up of officials from the FBI and departments of State, Treasury, Defense and Justice, as well as the Office of Director of National Intelligence and the CIA.

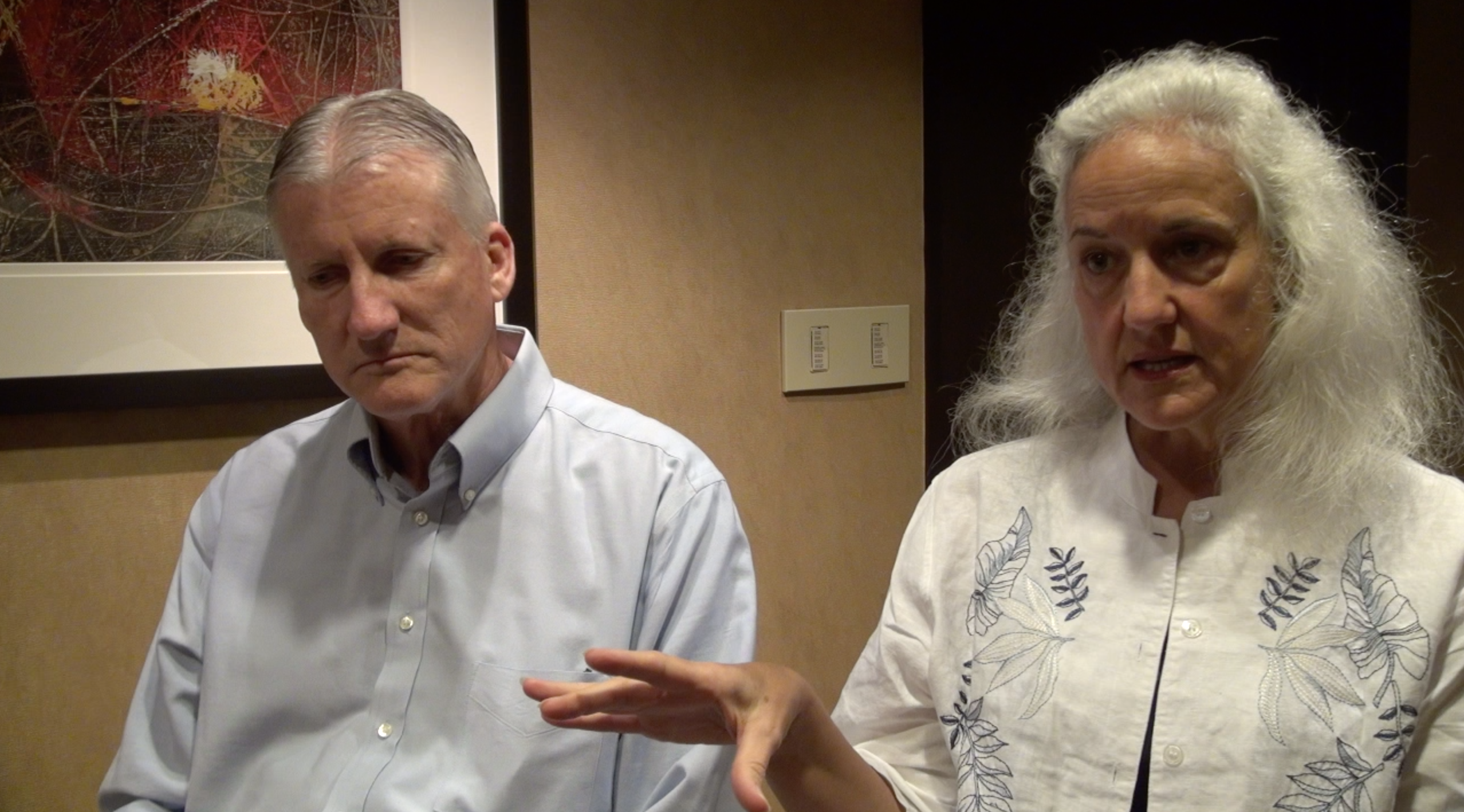

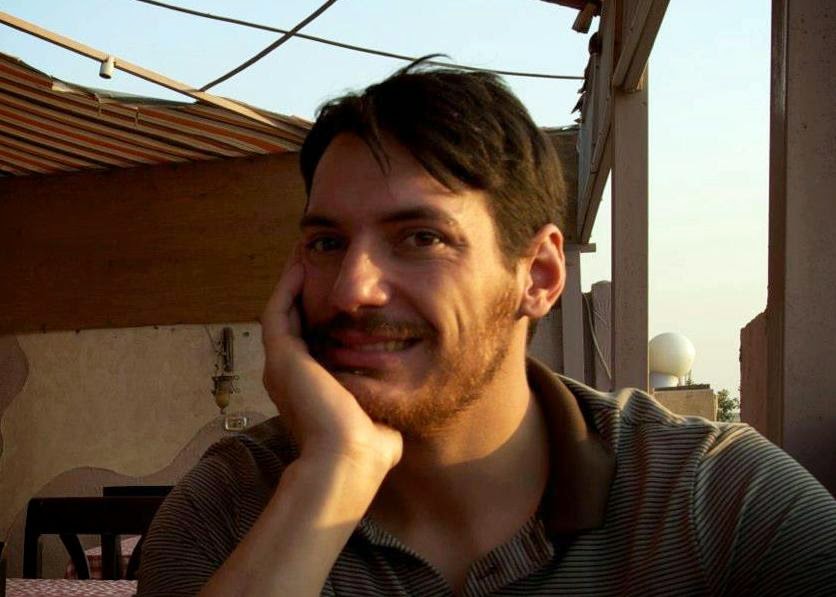

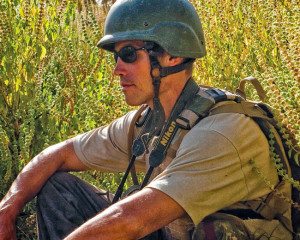

Marc and Debra Tice flew to Washington in June to meet with Obama to review his executive order revising U.S. hostage policy. Austin Tice, their son, is a freelance journalist who was kidnapped while reporting in Syria in August 2012.

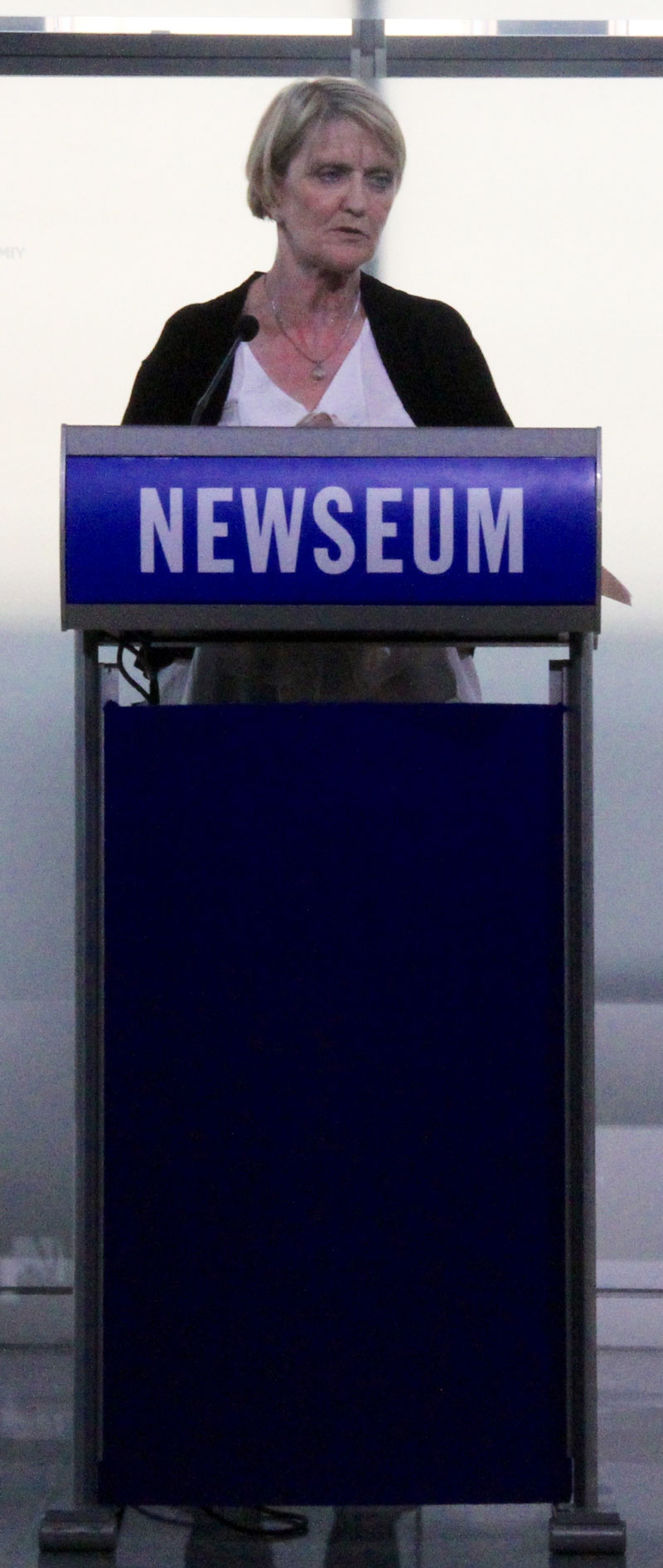

Speaking just days after their meeting with the president, the Tices expressed frustration at the difficulties they personally faced navigating the complicated system while trying to find their son.

“We spent two years figuring out who do you call, who’s got responsibility, who’s got capabilities, who’s got the desire, so we had to find our way through Washington and the bureaucracy and these different agencies of the government by ourselves effectively,” Marc Tice said.

“All of these resources already exist,” added Debbie Tice. “What we are really asking for is more efficient, more effective, more economical stewardship of resources.” The Tices spoke of institutional roadblocks at both the macro and micro, day-to-day levels.

“He has got an apartment that he is running, how do we deal with that? He has got bank accounts and student accounts, a social media identity… there’s a whole ecosystem that we have to go through,” Marc said.

“Think about the bank account that has nothing going into it, and has automatic payments coming out. And how quickly that can become a huge issue that we can’t get our hands around,” said Debbie.

The Tices said it took the family over a year to figure out a legal authority to deal with this issue. They still have not been able to access Austin’s Twitter account, from which he last tweeted about spending the day at Free Syrian Army pool party on August 11, 2012.

A Defense Department official who spoke on the condition of anonymity explained how circuitous government efforts between the White House, the State Department, the Central Intelligence Agency, the National Security Agency, the FBI, the Pentagon and the military services can be – especially when these agencies are all uniquely involved in different aspects of hostage recovery.

“Start with authority. Who has the authority to act for civilians?” the defense official said.

“One major criticism the Obama administration has faced is treating terrorism as a criminal activity,” he said. “Despite the ‘war on terrorism,’ we don’t treat it as a war, but as a crime.”

“If you’re in an Afghani combat zone, you’re DOD responsibility. Otherwise, you’re an FBI issue, unless you get a security order from the Secretary of Defense.

“So the FBI has the lead, but technically no overseas reach. You can only get there through the State Department and Department of Defense. And the FBI can’t tell DOD to do anything. And DOD would still need to get an execution order to do anything anyways.

“For the FBI, State and these agencies are peers – you can’t just tell them what to do. They would have to be told, pretty much, by the President. The CIA chain is just like State. They’d need presidential findings… they can’t just do a one-off. The DOD would need to call over to the Joint Staff, and then go to the Secretary of Defense for an execution order, but that can take 2 years.”

While the defense official lauded the enhanced support for hostages and their families, he criticized organizing the fusion cell under the umbrella of the FBI.

“The organization with the least reach is now entirely responsible for getting hostages home. So this could be seen as a huge slap in the face for families.”

Rep. Duncan Hunter, R- Calif., has advocated for displacing the FBI from its traditional leadership role in hostage negotiations.

“The problem is…in Iraq, there is no FBI. In Syria, there’s no FBI. In Afghanistan, there’s no FBI. In war zones, you don’t have the FBI,” Hunter said in May, discussing an amendment to the 2016 National Defense Authorization Act on the House floor.

“What you have is the Department of Defense and different intelligence agencies. [They] are the ones who track the networks, know the networks, know who the bad guys are, know where the hostages may be and then, in case we actually get good intelligence, the Department of Defense and our intelligence communities, those are the people that would act on the intelligence, not the FBI.”

Chris Voss, former lead FBI hostage negotiator, had a different take.

“The issue is in agencies putting the right people in the right places, and they’ve now designated the right places. In kidnapping issues, the actual authority and responsibility rests with the FBI, which is in charge of investigating murders and kidnappings overseas. Moving the coordination to that effort over to the FBI makes more sense, and elevates responsibility to FBI to a higher level.”

Voss said that now the overall coordination should be easier and quicker because of the higher level of authority involved – “but it still comes down to the level of expertise of the person in the position. Did the people involved with the government do a very poor job over the past two years?”

“In all these ISIL instances, there’s been a complete absence of any evidence of government subject matter expertise. It’s time for the government to take a hard look at the people doing the jobs and see if they’re up to the task. And there’s no evidence that they are.”