Screenshot of Chelsea Manning’s Twitter page, captured on April 16, 2015.

WASHINGTON — WikiLeaks firestarter Chelsea Manning has found a way to communicate using Twitter from inside the United States Disciplinary Barracks’ maximum-security military prison.

She is currently serving a 35-year sentence for her espionage conviction at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Manning, who was Pvt. Bradley Manning at the time, was convicted of divulging classified emails to Wikileaks. In the case, Manning was also accused of transferring classified DoD video, State Department cables and a Microsoft Powerpoint presentation onto a non-work computer and subsequent dissemination, as well as giving intelligence to enemies of the state. You can view the charge sheets, published by cryptome.org, here and here.

Manning, who has been tweeting since April 3, 2015, issued a handwritten statement (which she mailed to FitzGibbon Media for subsequent posting to her Twitter account) explaining the setup on April 16.

As per the statement, Manning “reserved” the Twitter account (with the handle @xychelsea) in 2013, but only asked FitzGibbon Media President and founder Trevor FitzGibbon to build it out a few weeks back.

With help from the organization, a human-rights and entertainment strategic communications firm that also counts WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange and rock band System of a Down among its clientele, Manning has begun to maintain an active Twitter presence.

“This is a temporary arrangement until I can find a way to either access my account more easily, or find someone else willing to put in the labor of managing the account, like Courage to Resist or another volunteer,” the April 16 tweeted statement reads.

A senior media strategist with FitzGibbon Media, who provided details about the partnership on background, confirmed its collaboration with Manning and said that the goal is to get Manning’s account “Verified” status.

This status, signified by a small blue check mark on the right side of one’s name as displayed on a Twitter profile page, is a much-coveted badge of social media legitimacy. It essentially says that Twitter has endorsed the user as being the person who she claims to be.

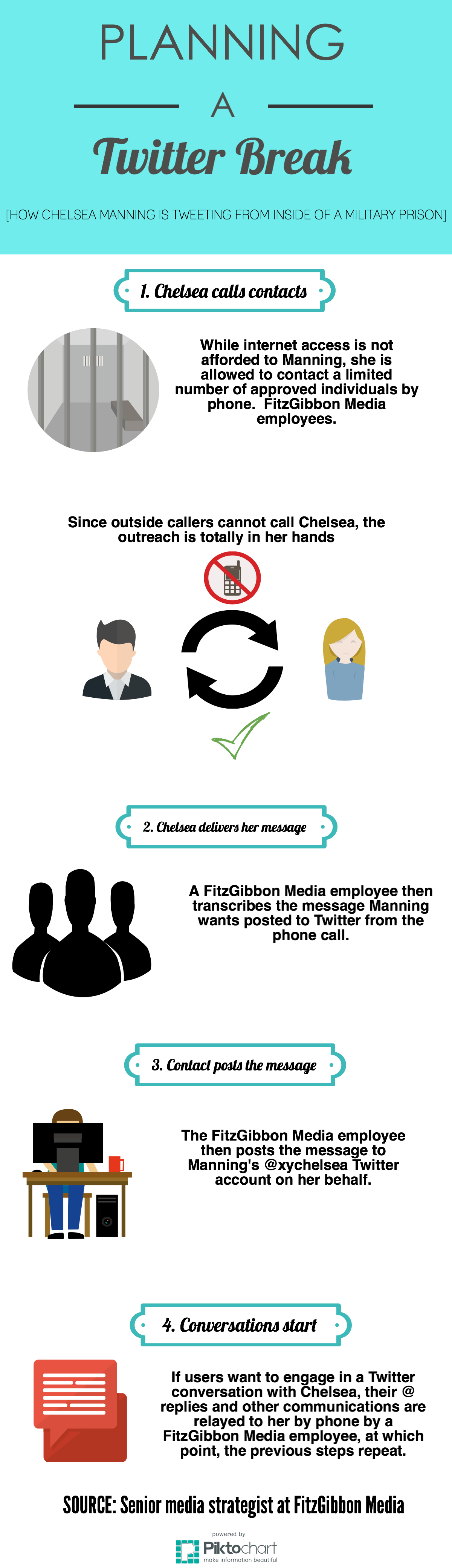

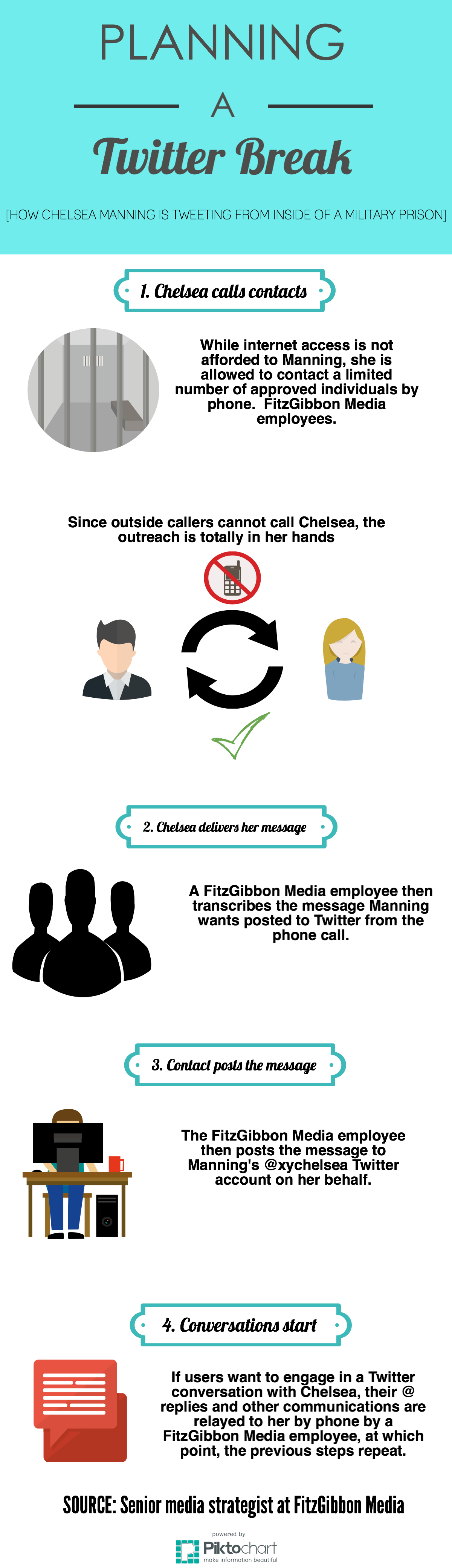

Here is how Chelsea Manning managed to plan a Twitter break:

The U.S. Army’s Take On the Situation

The U.S. Army’s Take On the Situation

“What third parties do, the Army has no control over,” said Army spokesman Wayne V. Hall.

According to Hall, “it is inappropriate to release information concerning individual inmates.” However, he confirmed that “inmates in the USDB do not have access to Twitter or the Internet.”

Still, Hall was able to provide insight as to some of the regulations placed upon USDB prisoners.

“Inmates are informed of acceptable methods of communication through the Manual for the Guidance of Inmates (USDB Regulation 600-1, Nov 2013),” he wrote in an email. “This document provides specific guidance on proper use of the telephone system, contact with news media representatives, written correspondence and visitation policies and procedures. The standards described apply to all inmates confined within the USDB.”

[Editor’s Note: The Medill NSJI filed a FOIA request to obtain a copy of the Manual for the Guidance of Inmates (USDB Regulation 600-1, Nov 2013) on April 17. If obtained, we will publish the document publicly via Document Cloud.]

According to Hall, USDB inmates have access to a phone system inside prison housing units. They each get a PIN number and are allowed to add 20 phone numbers to their account — kind of like an in-calling cellphone plan. He said inmates’ calls have a 30-minute time limit, but that they can make them as frequently as they want as long as they have enough money to cover the cost.

There are some caveats, though:

1. Not everyone gets approved to be on the OK-to-call list.

“Each request submitted by the inmate for telephonic contact is individually evaluated,” Hall explained via email. “However, unless expressly authorized, inmates are not allowed to talk on the telephone with the following: physicians (except those who are part of their legal defense team), Alcoholic Anonymous (AA) sponsors/contacts, college or university staff, commercial sources, halfway houses, congressmen, toll free numbers, former inmates, or friends/family of current or former inmates, and current or former 15th Military Police (MP) Brigade (BDE) staff members.”

2. Phone-call privacy is nearly nonexistent.

According to Hall, the only calls that aren’t monitored are those made between inmates and their lawyers.

3. When it comes to a journalist trying to hear an inmate’s voice, all bets are off.

“Per Army Regulation 190-47, face-to-face and telephonic communications between inmates and members of the news media are not authorized,” he wrote in the email. “Written communications are permitted.”

View Manning’s entire Twitter feed below, or view it on the site @xychelsea.