WASHINGTON – Drones – the same unmanned aircraft used for attacking the Taliban and killing Islamist terrorists – could soon come to a sky near you.

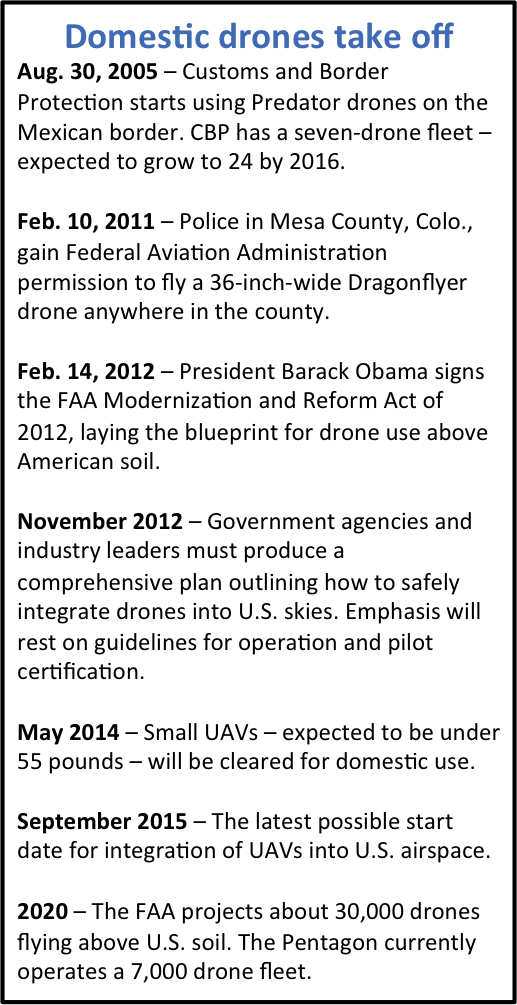

On Feb. 14, President Barack Obama signed the Federal Aviation Administration’s Modernization and Reform Act of 2012, accelerating the timetable for unmanned air vehicle use in U.S. skies. The bill greenlighted both public and private UAVs – or drones – for domestic liftoff by September 2015.

But privacy advocates are hotly protesting the law, warning that the FAA bill is the first step down a dangerous road to a surveillance society. UAVs’ high-tech cameras and sensors, they say, coupled with the current lack of regulation regarding drone use, could lead to a nation in which Big Brother watches from the sky.

The FAA previously blocked domestic UAV use due to safety concerns. But the military’s growing drone arm – they now make up a third of military aircraft – has driven improvements in the sense- and-avoid technology that helps prevent mid-air collisions.

Experts agree the bill opens the door for a commercial industry that could bring UAVs to any area from crop dusting to personal photography.

Drones’ main draw, however, is in the public sector – and therein lies their main controversy.

Advocates like Rep. Buck McKeon, R-Calif., say bringing UAVs to U.S. skies will lead to unprecedented gains in border defense, public safety and emergency response.

“Our state and local law enforcement agencies need a faster, more responsive process,” McKeon said in a statement. “Our neighborhoods deserve safer streets, and these systems can help provide that.

Opponents of the FAA bill don’t dispute drones’ policing capabilities. But they say the same components that allow drones to stalk and strike terrorists in the Middle East and South Asia will be used to scout crime scenes, follow suspects and patrol wide areas. Thermal imaging, for example, makes it easy to look at suspects inside buildings. And high-resolution cameras let operators follow several subjects simultaneously.

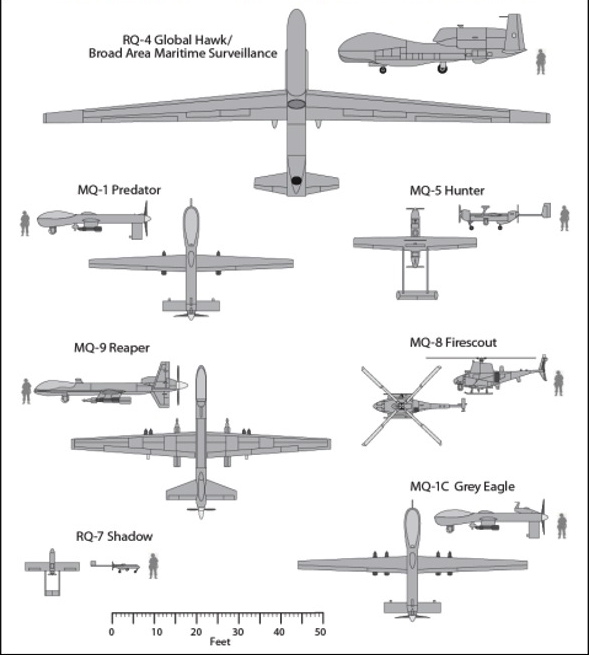

The rapidly improving technology is privacy advocates’ main concern. The FAA expects as many as 30,000 UAVs – as minute as small birds and as large as the 116-foot Global Hawk – to fly in U.S. skies in 10 years.

Keeping up with technology

“The technology is getting cheaper and more powerful and smaller,” said Jay Stanley, a policy analyst for the American Civil Liberties Union. “It’s entirely predictable that the use of this technology will spread greatly unless there are obstacles put in its way.”

Stanley wrote a December ACLU report urging the FAA to expand its regulations to include privacy measures – not just safety guidelines. Although the air agency has repeatedly denied this responsibility, civil liberties groups insist that ensuring personal privacy helps protect individuals on the ground.

If the FAA doesn’t consider privacy safeguards in its UAV regulations, advocates want Congress to fill the gap. The main concerns are overuses by government and law enforcement agencies that include mass surveillance, video retention and see-through imaging, Stanley said.

“It’s important that these protections be put in place in the infancy of this technology so that everybody understands the ground rules of the game,” he said.

But UAV supporters think otherwise. Ben Geilom, government relations manager for the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International, said current regulations for manned aircraft should extend to their unmanned counterparts.

“The aircraft itself…is new and maturing,” he said. “But the systems payload – the cameras and sensors that are on the unmanned system – are not new. In fact, they have been used by law enforcement and others on manned aircraft for decades.”

Small drones are able to hover outside of house windows to capture images and sounds, but that doesn’t mean it’s legal under current air regulations, Geilom said. Most of the privacy fears, he added, are due to unfamiliarity.

“With any new technology, there will certainly be the ability to abuse that technology,” Geilom said. “But there are also safeguards that are already in place that can serve as the framework.”

Complicating things further is that drone technology is progressing at a furious pace. The last time Congress passed a comprehensive FAA bill before February’s legislation was in 2003, when UAVs were in their infancy.

Future regulations should be limited to “broad safety parameters,” Geilom said, as more-detailed guidelines will be hard pressed to keep up with the accelerating technology.

“If unmanned aircraft can prove that it can seamlessly and safely integrate into the current manned aviation airspace…then they certainly should be able to integrate,” he said.

Public up in the air

Despite widespread support from law enforcement agencies and the defense industry, the public remains deeply divided over domestic drone use. A February Rasmussen poll found that only 30 percent of voters approve of UAVs flying in American skies. More than half, meanwhile, oppose it altogether.

Congress has thus far ignored any privacy concerns, including few regulations in the FAA bill and making no effort yet to add rules elsewhere.

Privacy advocates – notably the ACLU, Consumer Watchdog and the Electronic Privacy Information Center – called for added guidelines in a Feb. 24 petition to the FAA. Regulations must be added to keep up with UAV technology, they wrote, because drone use “poses an ongoing threat to every person residing in the United States.”

But law experts question the likeliness of such safeguards. Ryan Calo, director for Privacy and Robotics at Stanford University’s Center for Internet & Society, said that U.S. privacy law doesn’t hold back drone use.

The Supreme Court ruled in 1986 that no warrant was required for government agencies to take aerial photographs of a person’s backyard. And in 1989, the justices ruled that police do not need warrants to observe private property from public airspace.

“Citizens do not generally enjoy a reasonable expectation of privacy in public, nor even in the portions of their property visible from a public vantage,” Calo wrote in the Stanford Law Review. “Neither the Constitution nor common law appears to prohibit police or the media from routinely operating surveillance drones.”

Geilom and others within the UAV industry insist current rules for manned aircraft will suffice for domestic drones. Over-regulation of a potentially lucrative industry before it gets off the ground could squander opportunities for not only law enforcement, but also photographers, real estate agencies and farmers, they say.

Opponents, however, paint a much darker picture. Only a few hundred of the 19,000 law enforcement agencies in the country have a manned aircraft arm. Stanley said the ACLU fears that without further privacy protections, government organizations could overuse or mishandle such drone technology.

“That would fundamentally change the nature of our public spaces and public life and the nature of the relationship between an individual and government,” he said. “It’s not a road we should not go down.”