BY AARON RINEHART FOR THE MEDILL NSJI

“Encryption works. Properly implemented strong crypto systems are one of the few things that you can rely on. Unfortunately, endpoint security is so terrifically weak that NSA can frequently find ways around it.”

— Edward Snowden, answering questions live on the Guardian’s website

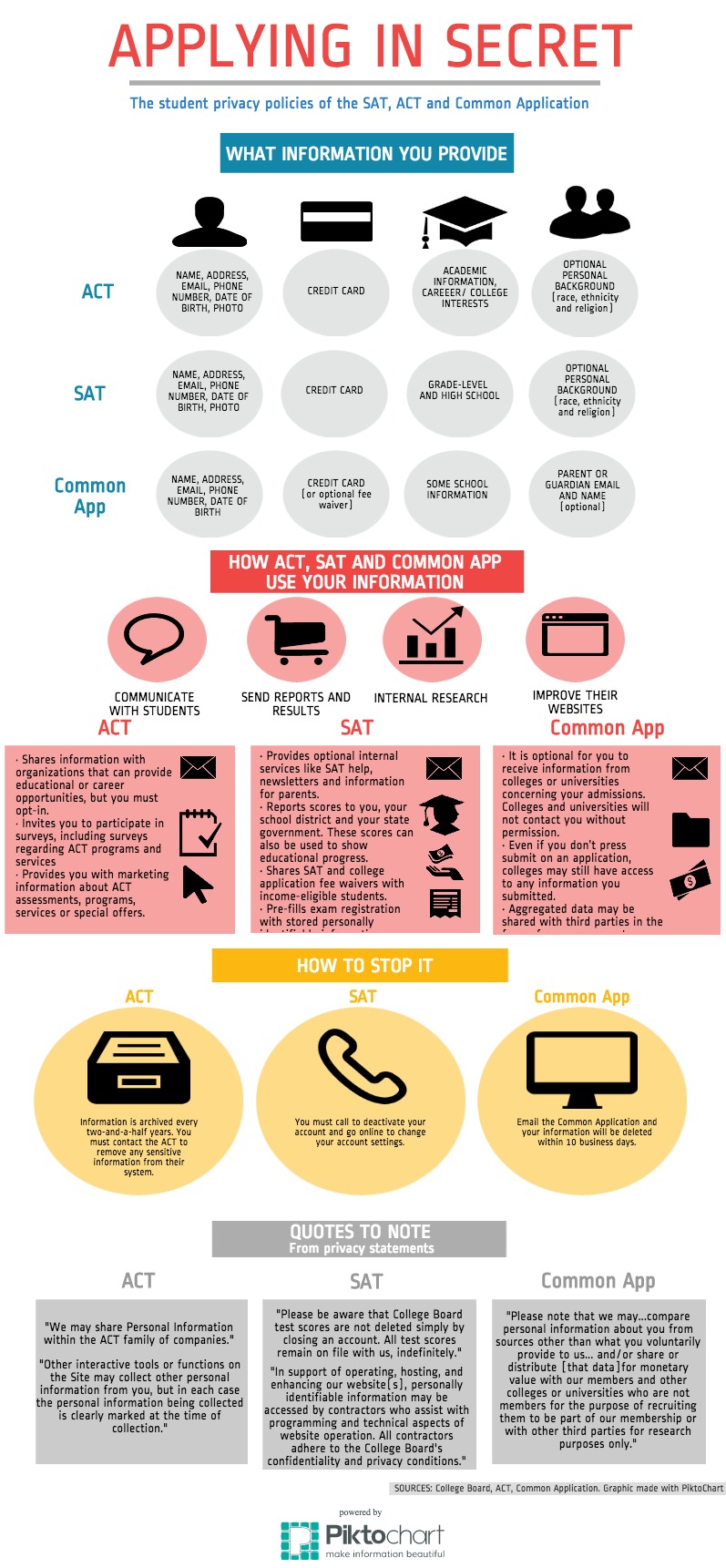

From surveillance to self-censorship, journalists are being subjected to increased threats from foreign governments, intelligence agencies, hacktivists and other actors who seek to limit or otherwise manipulate the information they possess. The notorious Edward Snowden stressed to the New York Times in an encrypted interview the importance of encryption for journalists: “It should be clear that [for an] unencrypted journalist to source communication is unforgivably reckless.” If journalists are communicating insecurely and without encryption, they put themselves, their sources and their reporting at unnecessary levels of risk. This sort of risky behavior may send the wrong message to potential key sources, like it almost did when Glenn Greenwald almost missed out on the landmark story of National Security Agency surveillance set out in the Snowden documents because he wasn’t communicating via encryption.

The aim of this how-to guide is to provide a clear path forward for journalists to protect the privacy of their reporting and the safety of their sources by employing secure communication methodologies that are proven to deliver.

How and When Should I Encrypt?

Understanding the basics of encryption and applying these tools and techniques to a journalist’s reporting is rapidly becoming the new normal when conducting investigative research and communicating with sources. It is, therefore, just as vital to know when and how to encrypt sensitive data as it is to understand the tools needed to do it.

In terms of when to encrypt, confidential information should be both encrypted “At-Rest” and “In-Transit” (or “In-Motion”). The term data-at-rest refers to data that is stored in a restful state on storage media. An example of this is when a file is located in a folder on a computer’s desktop or an email sitting in a user’s in-box. The term data-in-transit describes the change of data from being in a restful state to being in motion. An example of data-in-transit is when a file is being sent in an email or to a file server. With data-in-transit, the method of how the data is being transmitted from sender to receiver is the primary focus — not just the message. This is illustrated more effectively in the example of using a public wireless network in that if the network is not setup to use strong encryption to secure your connection, it may be possible for someone to intercept your communications. The use of encryption in this use case demonstrates how sensitive data, when not encrypted while in transit, can be compromised.

Methods for protecting Data-at-Rest and Data-in-Transit

Data-at-Rest can be protected through the following methods.

One suggested methodology is to encrypt the entire contents of the storage media, such as a hard drive on a computer or an external drive containing sensitive material. This method provides a higher level of security and can be advantageous in the event of a loss or theft of the storage media.

A second method – which should be ideally combined with the first method – is to encrypt the files, folders and email containing sensitive data using Pretty Good Privacy (or PGP) encryption. PGP encryption also has the added benefit of protecting data-in-transit, since the data stays encrypted while in motion

The name itself doesn’t inspire much confidence, but PGP or “Pretty Good Privacy” encryption has held strong as the preferred method by which individuals can communicate securely and encrypt files.

The concepts surrounding PGP and getting it operational can often seem complex, but this guide aims to make the process of getting started and using PGP clearer.

PGP Essentials: The Basics of Public and Private Keys

Before diving too deeply into the software setup needed to use PGP, it is important to understand a few key fundamentals of how PGP encryption works.

Within PGP and most public-key cryptography, each user has two keys that form something called a keypair. The reason the two keys are referred to as a keypair is that the two are mathematically linked.

The two keys used by PGP are referred to as a private key, which must always be kept secret, and a public key, which is available for distribution to people with whom the user chooses to communicate. Private keys are predominantly used in terms of email communications to decrypt emails from a sender. Public keys are designed for others to use to encrypt mail to the user.

In order to send someone an encrypted email, the sender must first have that recipient’s public key and have established a trusted relationship. Most encryption systems in terms of digital communications are based on establishing a system of trust between communicating parties. In terms of PGP, exchanging public keys is the first step in that process.

Key Management: Best Practices

Regardless of whether the user is using the OpenPGP standard with GNU Privacy Guard (GPG) or another derivative, there are a few useful points to consider in terms of encryption key management.

Private Keys are Private!

The most important concept to remember is that private Keys should be kept private. If someone compromises the user’s private key, all communications would be trivial to intercept.

Generating Strong Encryption Keys

When generating strong private/public keypairs there are some important things to remember:

- Utilize Large Key Sizes and Strong Hashing Algorithms

It is recommended that when generating a keypair to make the key size at least 4096bit RSA with the SHA512 hashing algorithm. The encryption key is one of the most important pieces in terms of how the encryption operations are executed. The key is provided to present a unique “secret” input that becomes the basis for the mathematical operations executed by the encryption algorithm. A larger key size increases the strength of the cryptographic operations as it complicates the math due to the larger input value. Thus, it makes the encryption more difficult to break.

- Set Encryption Key Expiration Dates

Choose an expiration date less than two years in the future.

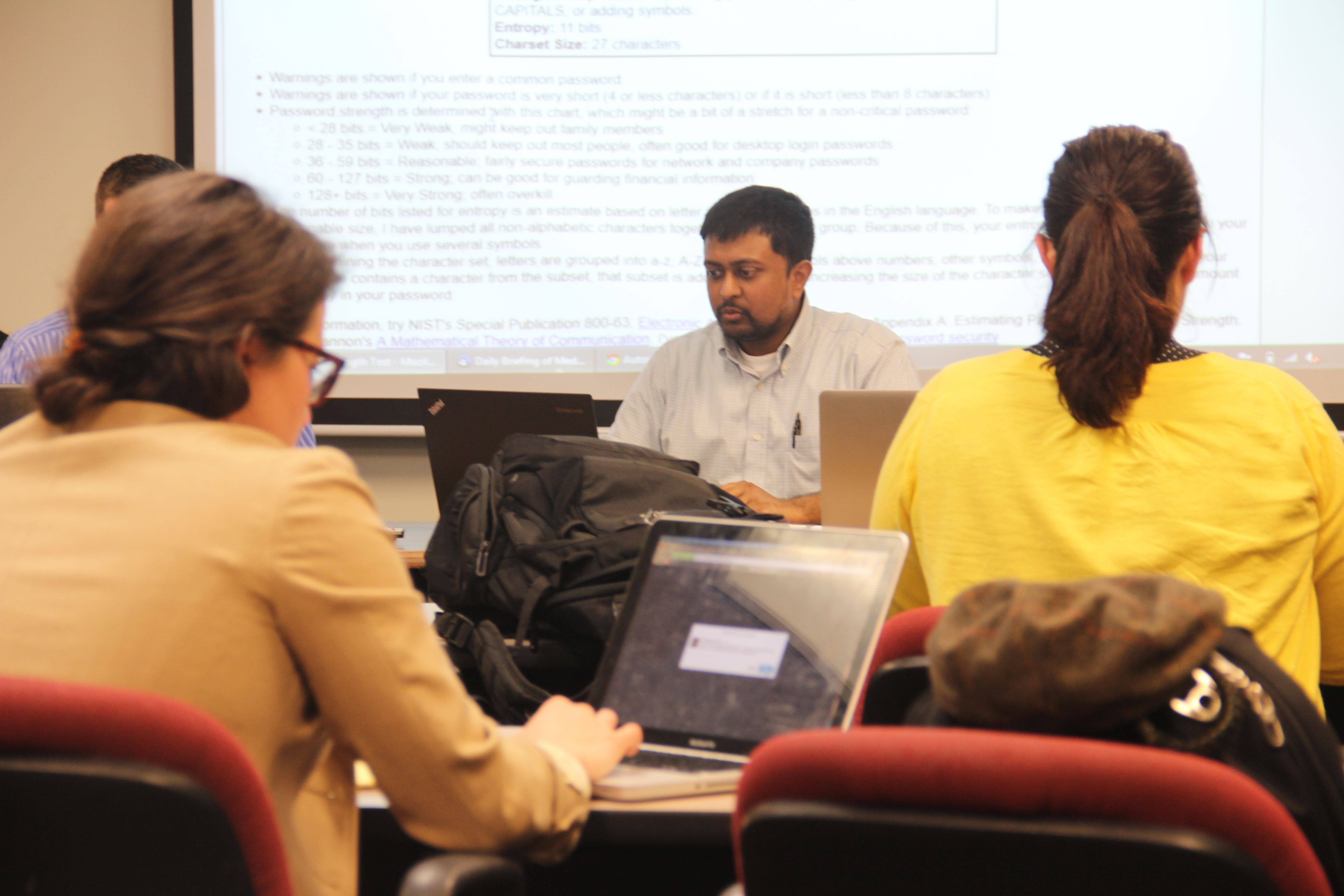

From a security perspective, the passphrase is usually the most vulnerable part of the encryption procedure. It is highly recommended that the user choose a strong passphrase.

In general terms, the goal should be to create a passphrase that is easy to remember and to type when needed, but very hard for someone else to guess.

A well-known method for creating strong, but easy to remember, passwords is referred to as ‘diceware,’. Diceware is a method for creating passphrases, passwords and other cryptographic variables using an ordinary die from a pair of dice as a random number generator. The random numbers generated from rolling dice are used to select words at random from a special list called the Diceware Word List. The recommendation when using diceware to create a PGP passphrase is to use a minimum of six words in your passphrase. An alternative method for creating and storing strong passphrases is to use a secure password manager such as KeePass.

Backing Up Private Keys

Although a journalist may be practicing good security by encrypting sensitive information, it would be devastating if a disruptive event – such as a computer hardware failure – caused them to lose their private key, as it would be near-impossible to decrypt without it. When backing up a private key, it is important to remember that is should only be stored on a trusted media, database or storage drive that is preferably encrypted.

Public Key Servers

There are several PGP Public Key servers that are available on the web. It is recommended for journalists upload a copy of their public keys to public key servers like hkp://pgp.met.edu to open their reporting up to potential sources who wish to communicate securely. By uploading a copy of the public key to the key server, anyone who wants to communicate can search by name, alias or email address to find the public key of the person their looking for and import it.

Validating Public Keys: Fingerprints

When a public key is received over an untrusted channel like the Internet, it is important to authenticate the public key using the key’s fingerprint. The fingerprint of an encryption key is a unique sequence of letters and numbers used to identify the key. Just like the fingerprints of two different people, the fingerprints of two different keys can never be identical. The fingerprint is the preferred method to identify a public key. When validating a public key using its fingerprint, it is important to validate the fingerprint over an alternative trusted channel.

For example, if a journalist receives a public key for a source on a public key server, it is important for them to validate the key by either communicating in person, calling them over secure phone or via an alternate communication channel. The purpose of key validation is to guarantee that the person being communicated with is the key’s true owner.

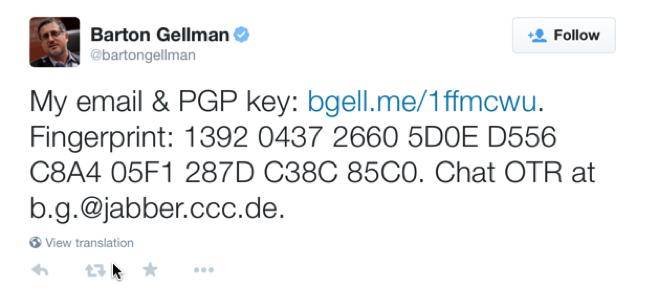

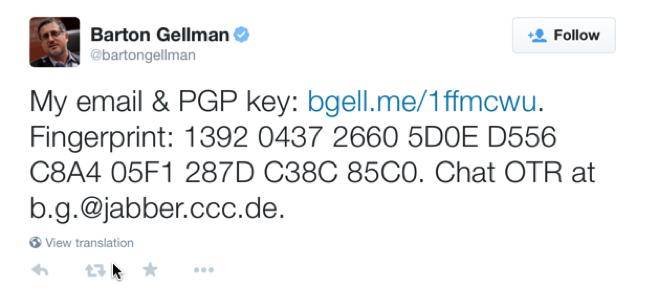

Adding PGP Public Key Fingerprint to Twitter

For journalists, its important to ensure sources can quickly validate their public keys that they retrieve from Public Key servers. A common method to convey a PGP public key to the public is to tweet the public key fingerprint and link to that tweet in to the bio.

Another method is to link directly to the PGP key on a public keyserver (like MIT’s) and to provide a copy of the key fingerprint in the bio, like this example with Barton Gellman.

GNU Privacy Guard: Encrypting Email with GPG

Hold up, stop and wait a minute: I thought the topic of discussion was PGP.

Is GPG a typo?

No. In fact, GPG (or the GNU Privacy Guard) is the GPL-licensed alternative to the PGP suite of encryption software. Both GPG and PGP utilize the same OpenPGP standard and are fully compatible with one another.

Getting Started with GPG: From Setup to Secure

A Step-by-Step Guide to Setting up GPGTools on Apple OSX

Tutorial Objectives

- How to install and configure PGP on OS X

- How to use PGP operationally

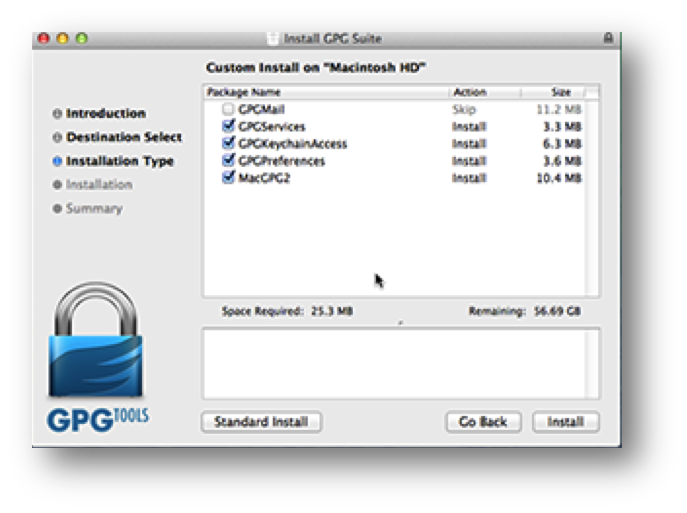

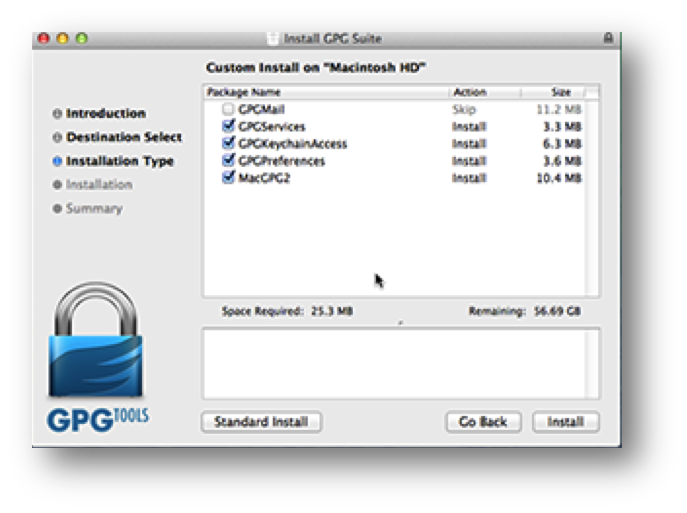

Install the GPGTools GPG Suite for OS X

This step is simple. Visit the GPGTools website and download the GPG Suite for OS X. Once downloaded, mount the DMG and run the “Install.”

Select all modules and, then, press “Install.”

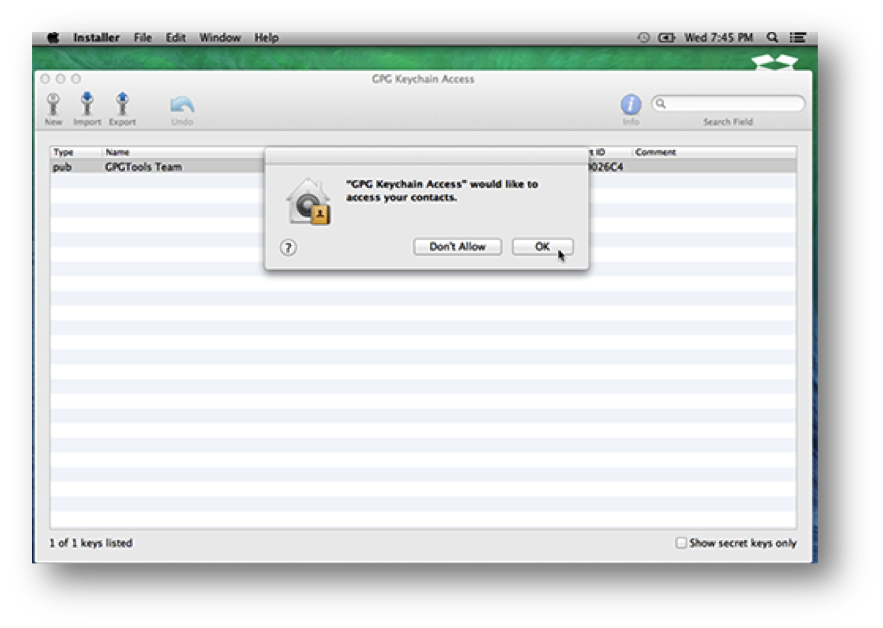

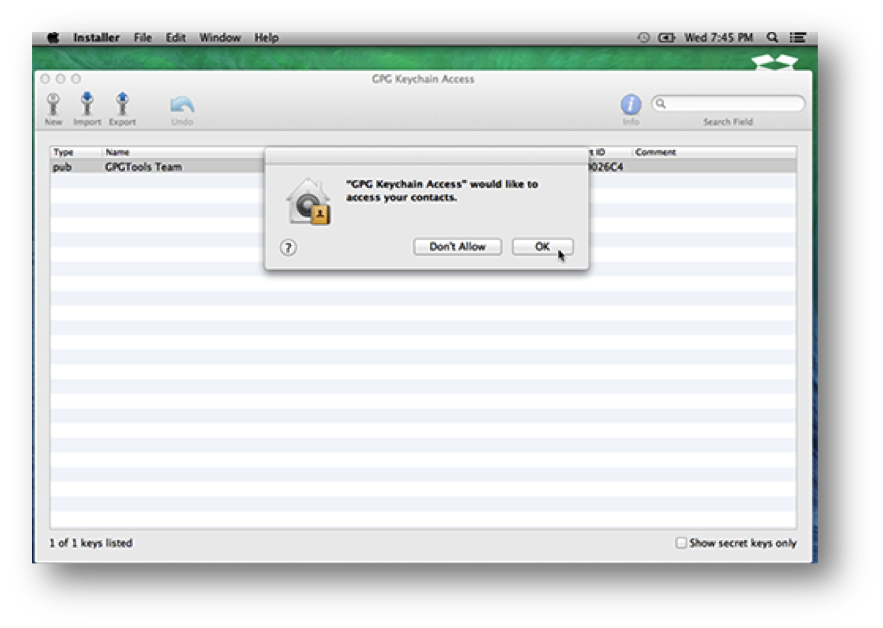

Generating a New PGP key

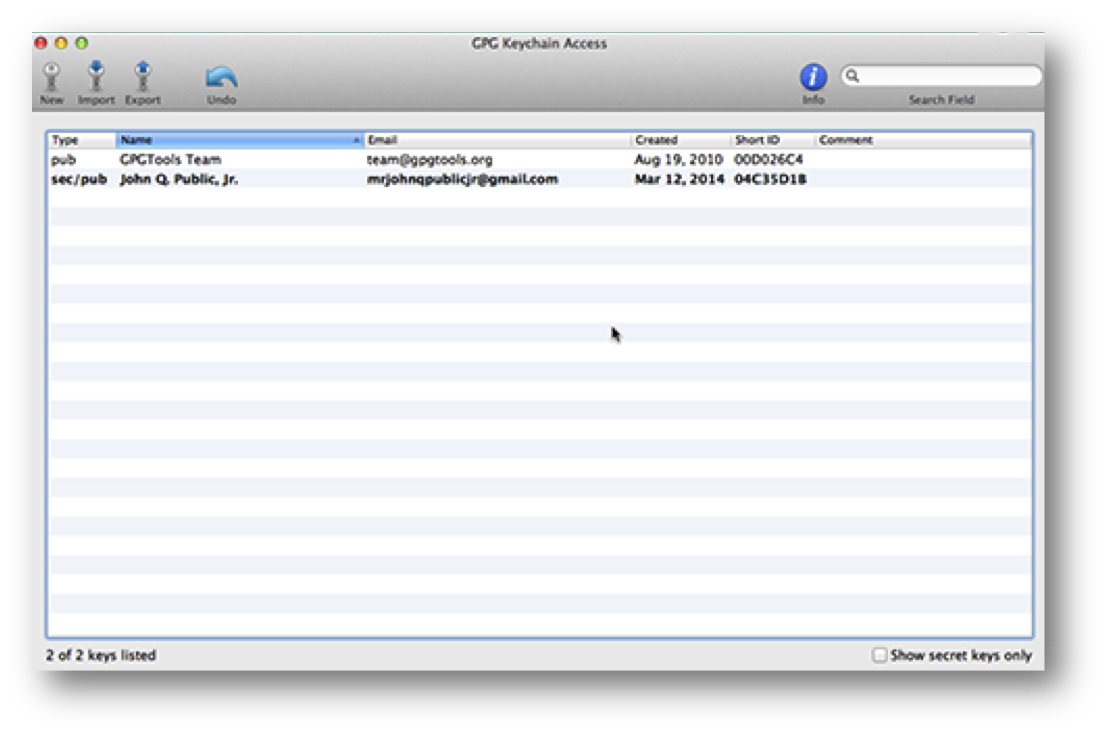

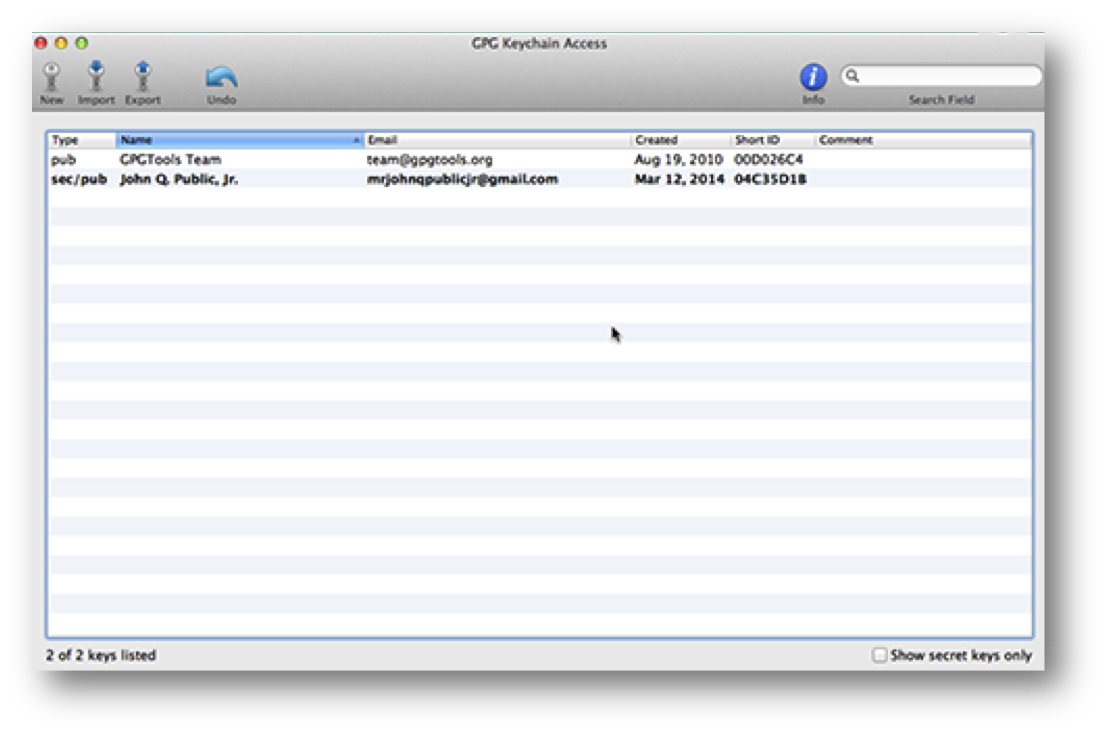

When the installer completes, a new app called “GPG Keychain Access” will launch. A small window will pop up immediately and say: “GPG Keychain Access would like to access your contacts.” Press “OK.”

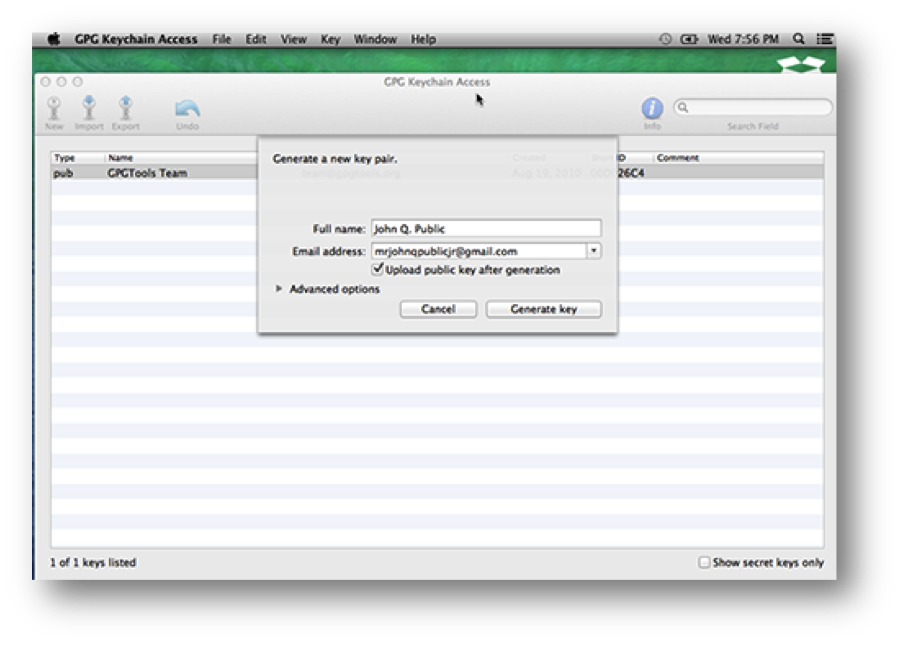

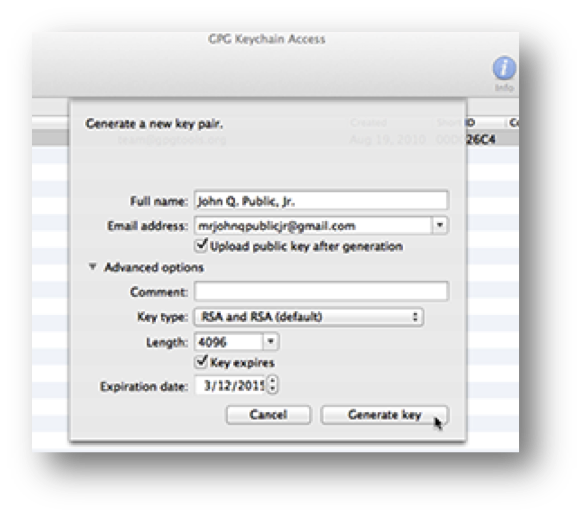

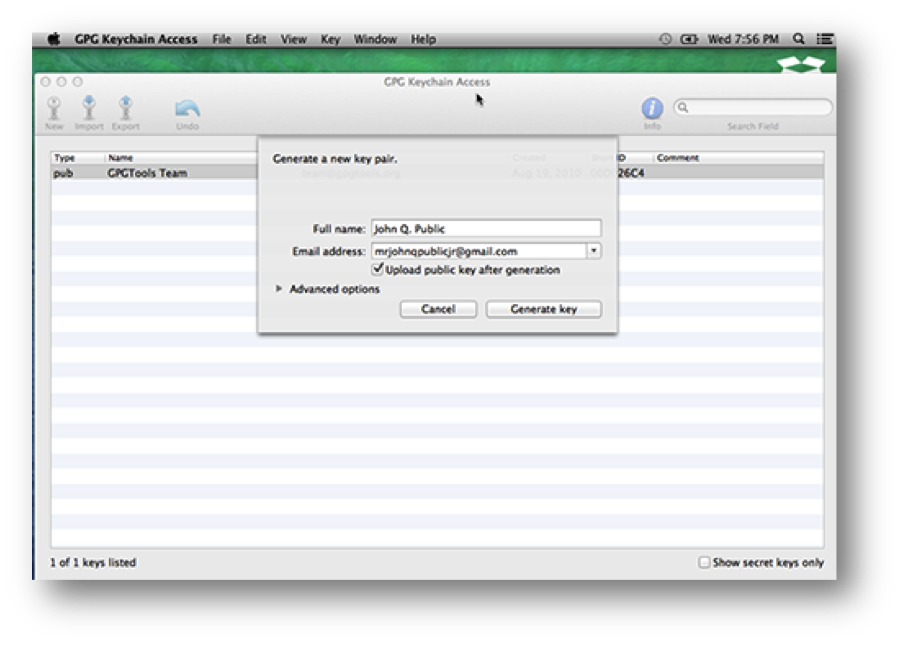

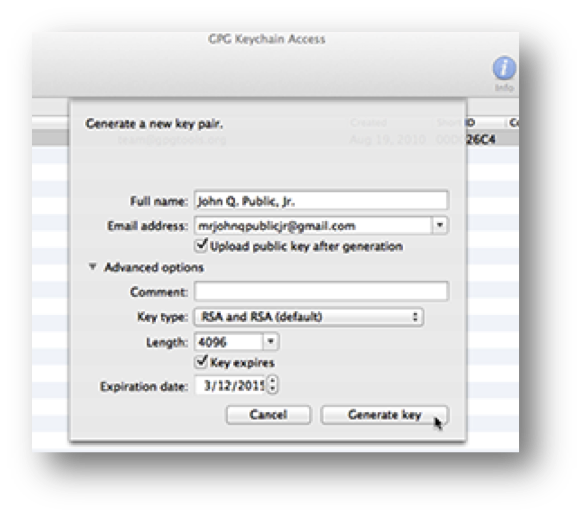

After pressing “OK,” a second window will pop up that says “Generate a new keypair.” Type in your name and your email address. Also, check the box that says “Upload public key after generation.” The window should look like this:

Expand the “Advanced options” section. Increase the key length to 4096 for extra security. Reduce the “Expiration date” to 1 year from today. The window should look like this:

Press “Generate key.”

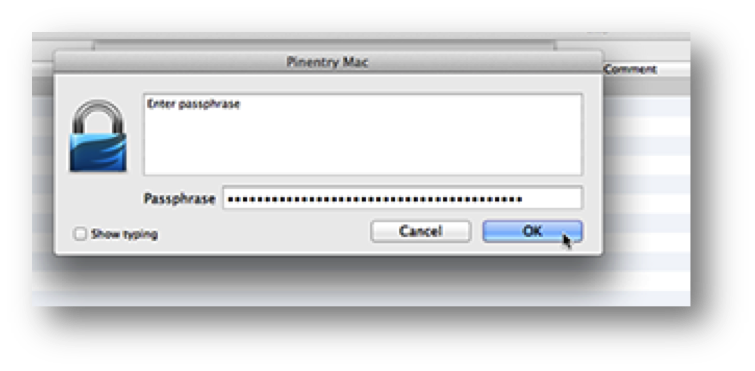

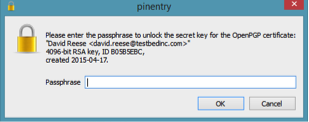

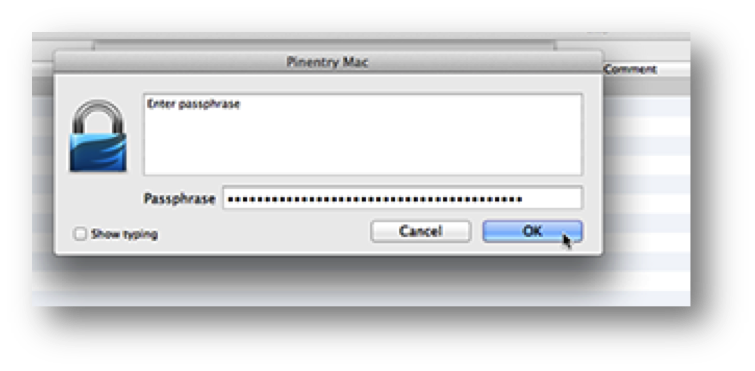

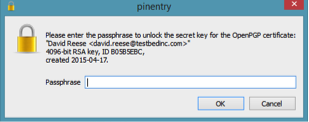

After pressing “Generate key,” the “Enter passphrase” window will pop up.

Okay, now this is important…

The Importance of Good Passphrases

The entire PGP encryption process will rest on the passphrase that is chosen.

First and foremost: Don’t use a passphrase that other people know! Pick something only you will know and others can’t guess. Once you have a passphrase selected, don’t give it to other people.

Second, do not use a password, but rather a passphrase — a sentence. For example, “ILoveNorthwesternU!” is less preferable than “I graduated from Northwestern U in 1997 and it’s the Greatest U on Earth?!” The longer your passphrase, the more secure your key.

Lastly, make sure your passphrase is something you can remember. Since it is long, there is a chance that you might forget it. Don’t. The consequences to that will be dire. Make sure you can remember your passphrase. In general there are several methodologies by which you can employ to store your passphrase to ensure its safekeeping. One such method would be to make use of a password manager like “KeePass”, an open source encrypted password database that securely stores your passwords.

Once you decide on your passphrase, type it in the “Enter passphrase” window. Turn on the “Show typing” option, so you can be 100% sure that you’ve typed in your passphrase without any spelling errors. When everything looks good, press “OK:”

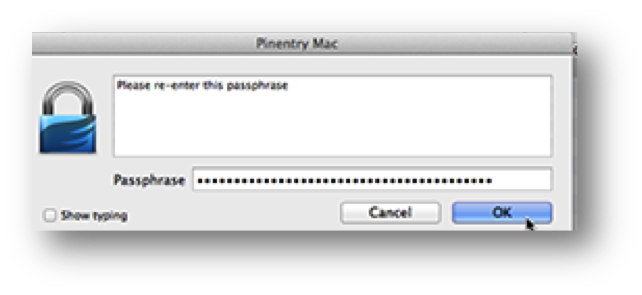

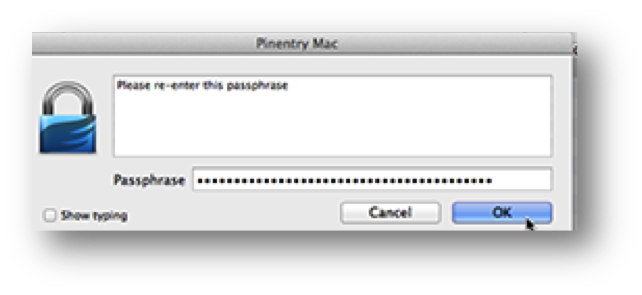

You will be asked to reenter the passphrase. Do it and press “OK:”

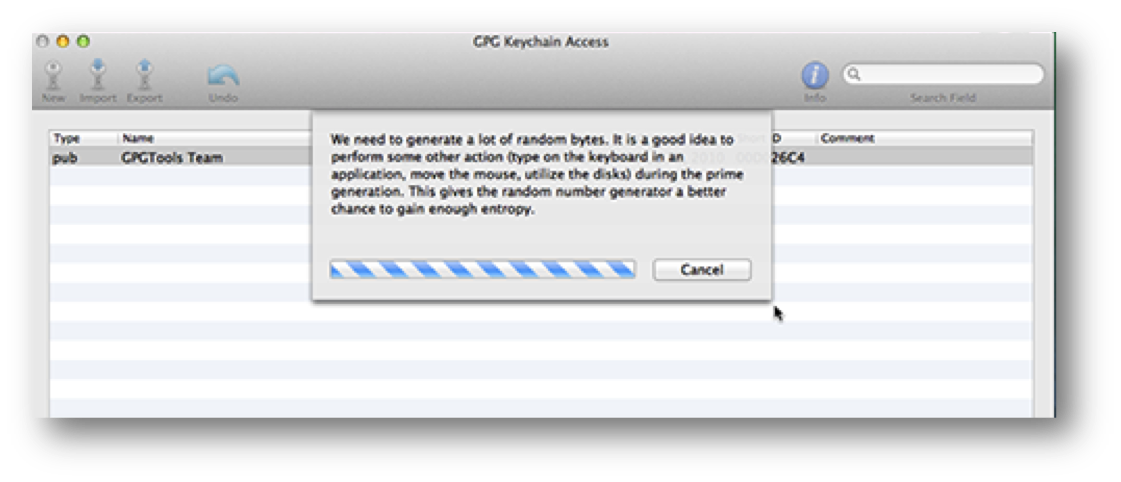

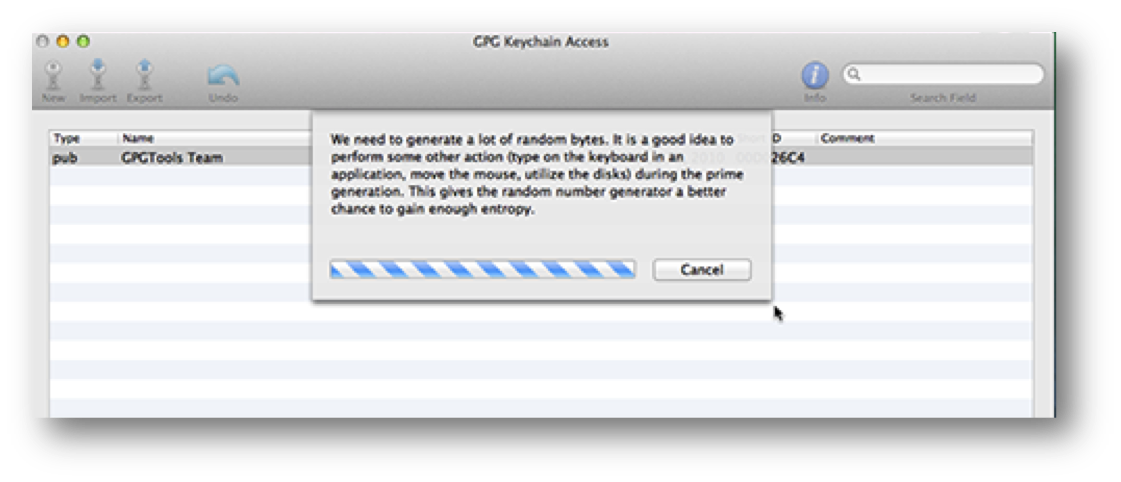

You will then see a message saying, “We need to generate a lot of random bytes…” Wait for it to complete:

Your PGP key is ready to use:

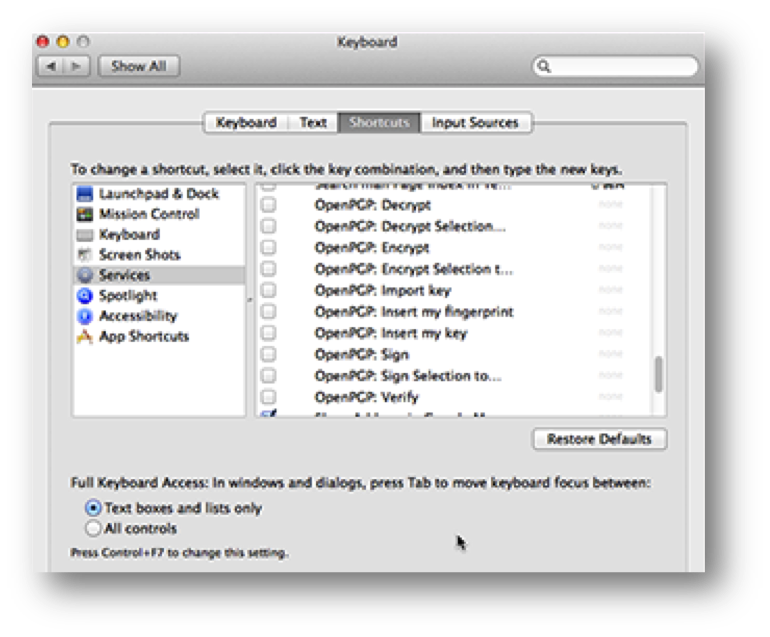

Setup PGP Quick Access Shortcuts

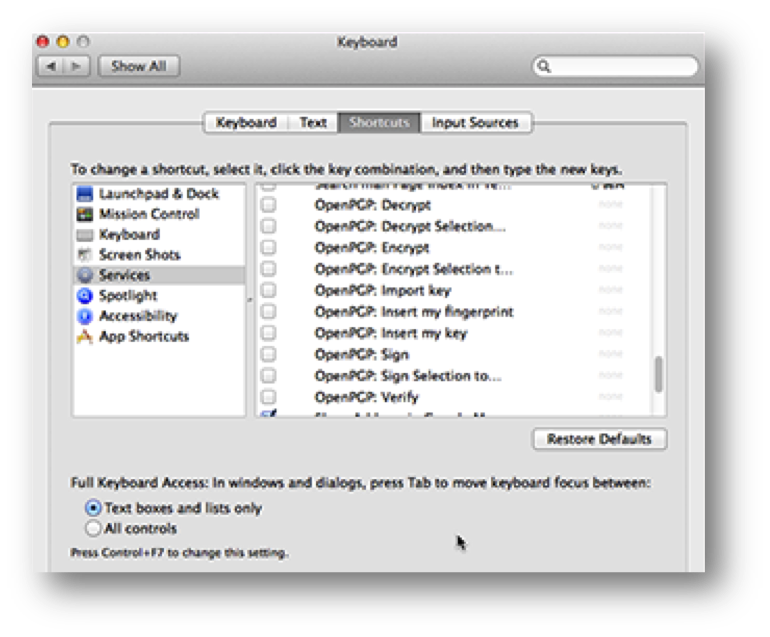

Open System Preferences, select the “Keyboard” pane and go to the “Shortcuts” tab.

On the left hand side, select “Services.” Then, on the right, scroll down to the subsection “Text” and look for a bunch of entries that start with “OpenPGP:”

Go through each OpenPGP entry and check each one.

Bravo! You’re now done setting up PGP with OpenGPG on OS X!

Now, let’s discuss how to use it.

How to send a secure email

To secure an email in PGP, you will sign and encrypt the body of the message. You can just sign or just encrypt, but combining both operations will result in optimum security.

Conversely, when you receive a PGP-secured email, you will decrypt and verify it. This is the “opposite” of signing and encrypting.

Start off by writing an email:

- Select the entire body of the email and “Right Click and Go to Services -> OpenPGP: Sign” to sign it.

- Open the GPG Keychain Access app. Select “Lookup Key” and type in the email address of the person you are sending your message to. This will search the public keyserver for your source’s PGP key.

If your source has more than one key, select his most recent one.

You will receive a confirmation that your source’s key was successfully downloaded. You can press “Close.”

You will now see your source’s public key in your keychain.

- You can now quit GPG Keychain Access and return to writing the email.

- Select the entire body of the email (everything, not just the part you wrote) and “Right Click and Go to Services -> OpenPGP: Encrypt” to encrypt it. A window will pop up, asking you who the recipient is. Select the source’s public key you just downloaded and press “OK.”

- Your entire message is now encrypted! You can press “Send” safely.

As a reminder, you will only need to download your source’s public key once. After that, it will always be available in your keychain until the key expires.

How to receive a secure email

With our secure message sent, the recipient will now want to decipher it. For the sake of this step, I will pretend that I am the recipient.

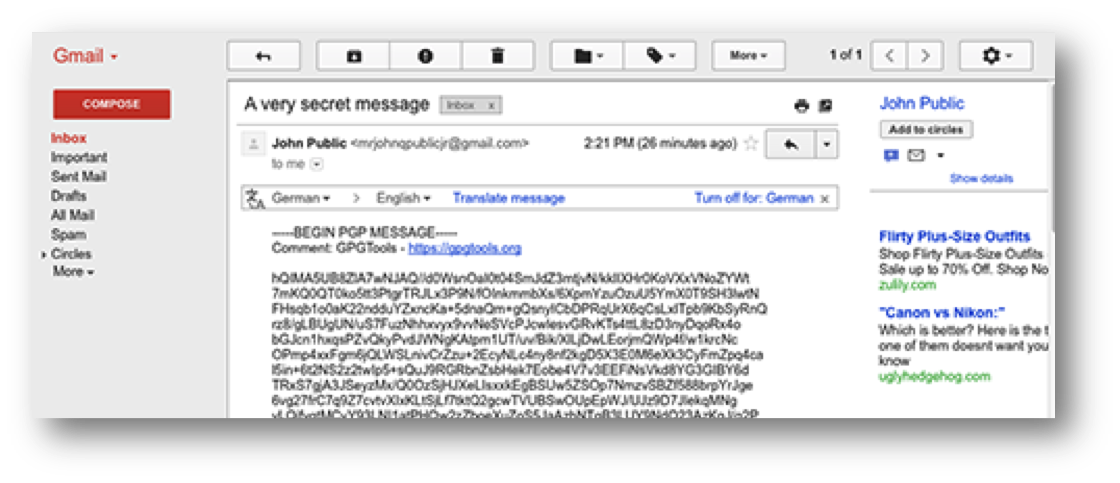

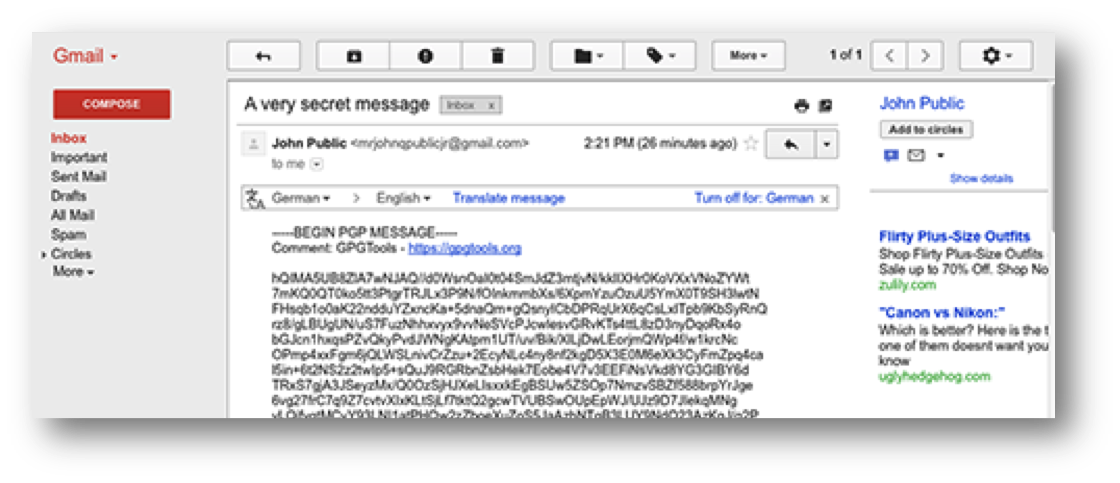

I have received the message:

- Copy the entire body, from, and including, “—–BEGIN PGP MESSAGE—“, to, and including, “—–END PGP MESSAGE—“. Open a favorite text editor, and paste it:

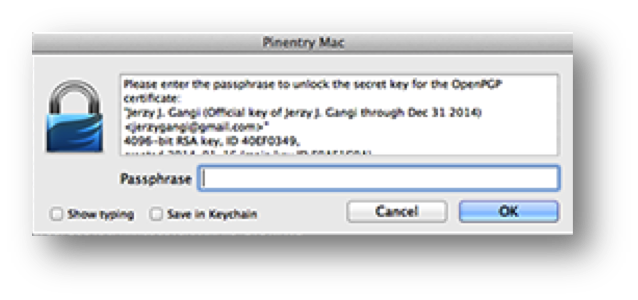

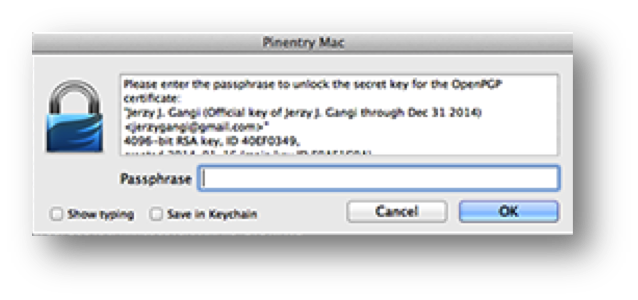

- Select the entire text, “Right click and select Services – OpenPGP – Decrypt” – to decrypt the message. You will immediately be prompted for your PGP passphrase. Type it in and press “OK:”

- You will now see the decrypted message!

Next, you can verify the signature.

Next, you can verify the signature.

- Highlight the entire text and “Right Click and Go to Services -> OpenPGP: Verify”. You will see a message confirming the verification.

- Press “OK.”

Setting up GPG4Win on Windows

Tutorial Objectives

- How to install and configure PGP on a PC

- How to use PGP operationally

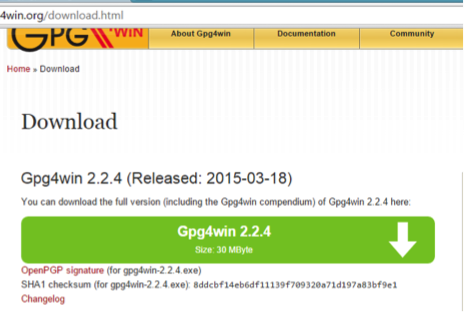

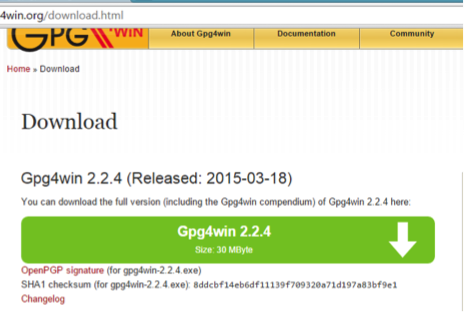

Installing the GPG4Win GPG Suite

This step is simple.

- Visit the GPG4win website and download the GPG Suite for OS X.

- Once downloaded, run the “Install”.

Download Install File

- Double-Click on the downloaded file to begin the installation wizard.

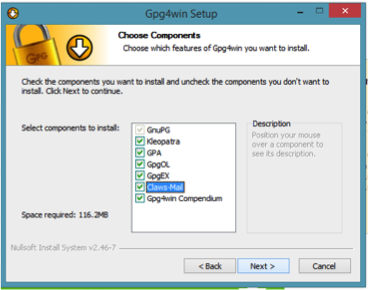

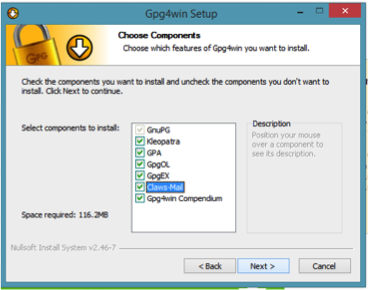

- Select the components to install, but keep it simple by installing all components except for Claws Mail.

- Select “Next”

A brief description of each component:

- Kleopatra – a certificate manager

- GPA – another certificate manger

- GpgOL – a plugin for Outlook

- GPGEX – an extension for Windows Explorer

- Claw-Mail – a lightweight email program with GnuPG support built-in

- Gpg4win Compendium – a manual

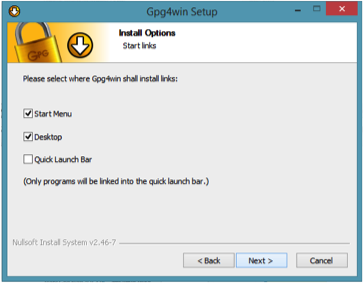

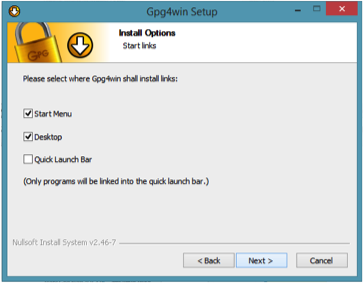

- Select desired preferences and click “Next”

5. Click “Finish” to exit the install wizard.

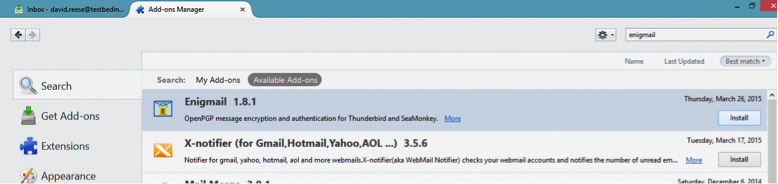

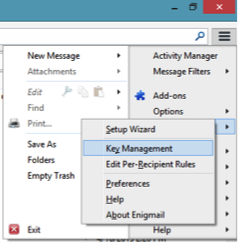

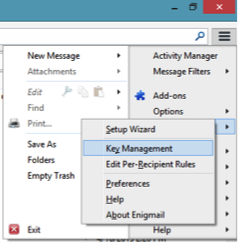

Setting up GPG4Win using Thunderbird and Enigmail

Enigmail, a play on words originating from the Enigma machine used to encrypt secret messages during World War I, is a security extension or add-on to the Mozilla Thunderbird Email software. It enables you to write and receive email messages signed and/or encrypted with the OpenPGP standard. Enigmail provides a more simplified method for sending and receiving encrypted email communications. This step-by-step guide will help you get started installing and configuring the extension.

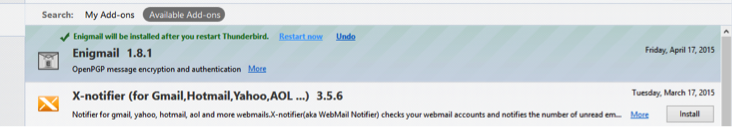

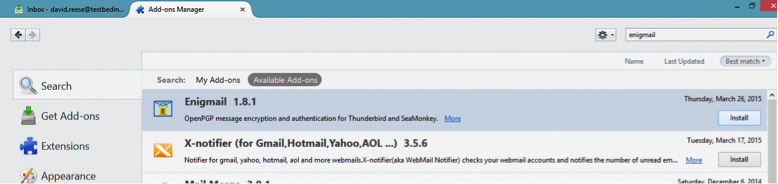

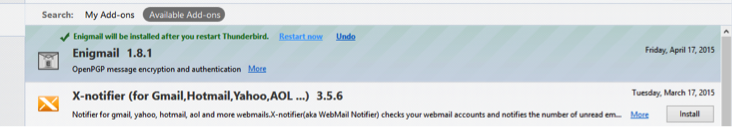

- Open Thunderbird and navigate to the Add-Ons Manager under the “Tools” menu.

- In the search dialog box, type “Enigmail.”Now, a list of Add-Ons will be available.

- Select the Enigmail add-on from the list.

- Click the “Install” button.

- There should now be a message indicating, “Enigmail will be installed after you restart Thunderbird.” Proceed with the installation by Clicking on the words “Restart Now”

- After the Thunderbird application restarts, Enigmail should look like the image below. Proceed with configuring the add-on by Selecting Enigmail from the list.

- Select “I prefer a standard configuration (recommended for beginners)” and click “Next”.

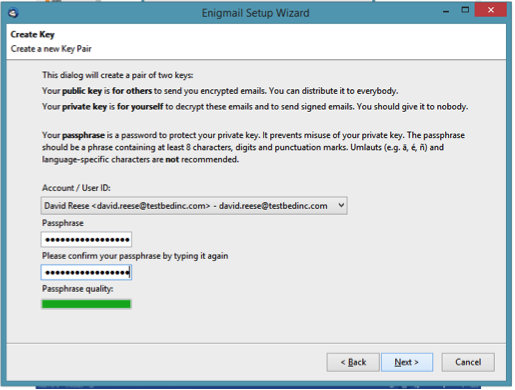

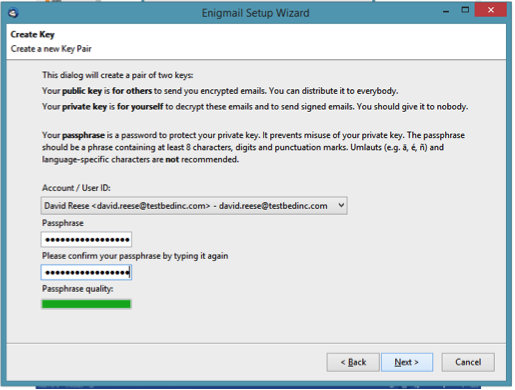

Generating a Public/Private Keypair.

- Select the Account to generate the keys for.

- Enter in a strong passphrase

- If the passphrase isn’t strong enough, the Passphrase quality meter will indicate that with a red- or yellow-colored bar (vs. the green one shown in the image below).

- Re-enter the strong passphrase to confirm.

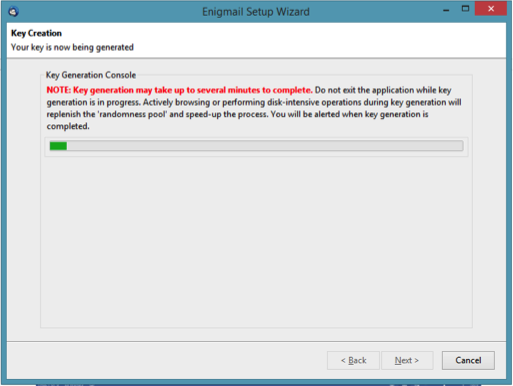

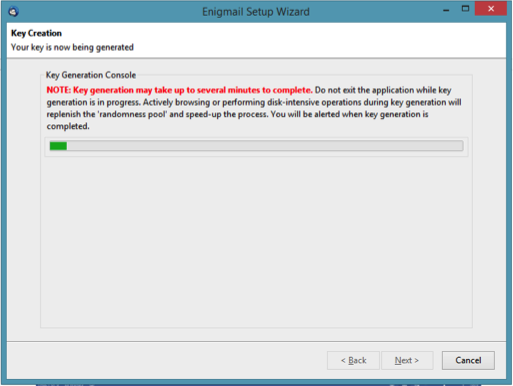

The Key Generation Process will generate a series of data based on random activity and assign it to the randomness pool for which to generate the keypair.

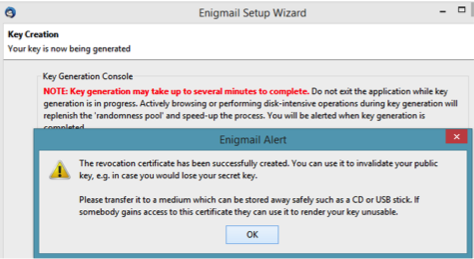

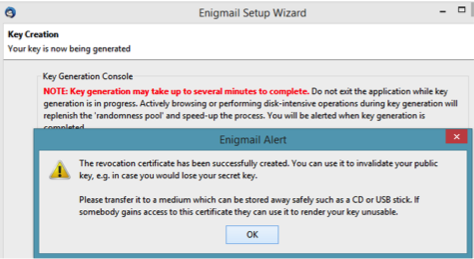

- Save the revocation key to a trusted and safe, separate device (storage media)!

The revocation certificate can be used to invalidate a public key in the event of a loss of a secret (private) key.

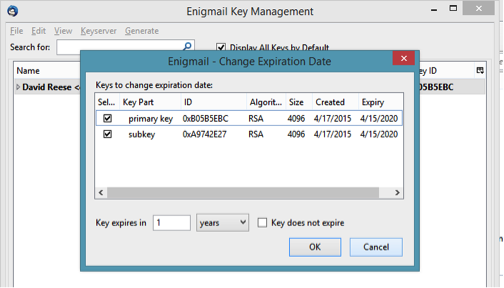

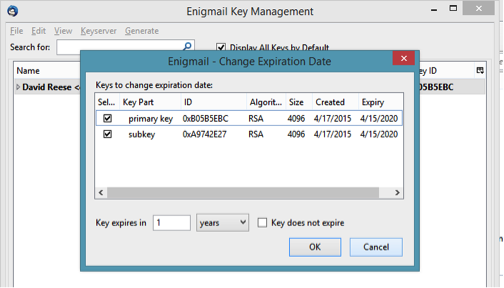

Key Management / View Key in Enigmail

- Change the expiration date (suggested <2 years)

- Upload Key To Public Keyserver (like hkp://pgp.mit.edu).

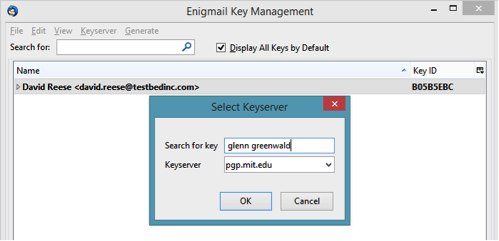

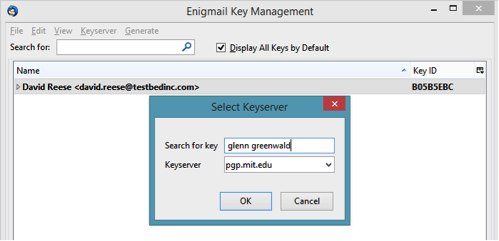

Public Keyserver Lookup

Look up the Public Keys of other people on public keyserver directly from within Enigmail.

- Select “Search for Keys” from the “Keyserver” dropdown menu.

- Enter in the Email Address or <FirstName><space><LastName> of the persons name that is being looked up.

A good test for this function is to try searching for Glenn Greenwald.

Notice how many active public keys Glenn Greenwald has. This could be intentional, but it can also happen when setting up keys on a new device or email client and 1. Forgot the private key passphrase 2. Lost the key revocation file or forgotten the passphrase to unlock it.

The problem is that anyone contacting the user for the first time will have to figure out which key is the correct one to use. It also becomes a security risk because any one of those unused, but active, keys could be compromised, and result in adversaries accessing communications.

MORAL Of THE STORY: Set an expiration date, manage the revocation key file and manage passphrases.

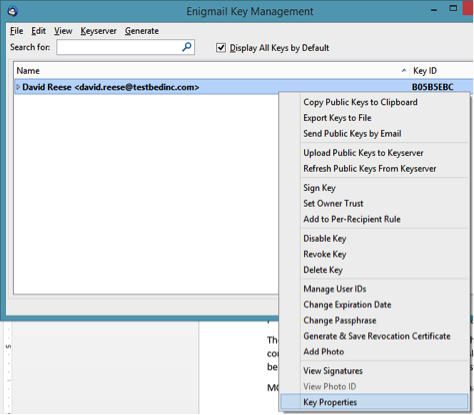

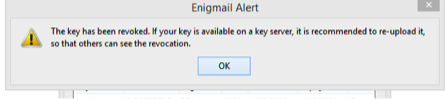

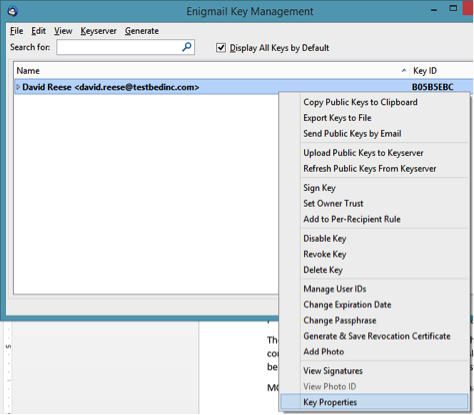

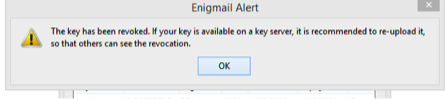

Revoking a Key

- Right-click on the key and click on Key Properties.

- At the bottom of the window Click on the ”Select Action” dropdown menu and Select “Revoke Key.”

- A dialog box will pop up asking for the Private Key’s unique passphrase. Enter the passphrase for the key that is being revoked.

- Once completed, the user will receive an ‘Enigmail Alert’ indicating that the key has been revoked. The alert warns the user that ‘if your key is available on a keyserver, it is recommended to re-upload it, so that others can see the revocation’. It is important to update the public keyservers to ensure that sources are aware of revoked keys and new keys on each account.

Operationalizing GPG: A Pragmatic Approach

What do encrypt, decrypt, sign, and verify mean?

- Encrypt takes the user’s secret key and the recipient’s public key, and jumbles a message. The jumbled text is secure from prying eyes. The sender always encrypts.

- Decrypt takes an encrypted message, combined with the user’s secret key and the sender’s public key, and descrambles it. The recipient always decrypts. Encrypt and decrypt can be thought of as opposites.

- Signing a message lets the receiver know that the user (the person with the user’s email address and public key) actually authored the message. Signing also provides additional cryptographic integrity by ensuring that no one has interfered with the encryption. The sender always signs a message.

- Verifying a message is the process of analyzing a signed message to determine if the signature is true. Signing and verifying can be thought of as opposites.

When should someone sign a message? When should they encrypt?

If it is unnecessary to sign and encrypt every outgoing email, when should the user sign? And when should the user encrypt? And when should the user do nothing?

There are three sensible choices when sending a message:

- Do nothing. If the contents of the email are public (non-confidential), and the recipient does not care whether the user or an impostor sent the message, then do nothing. The user can send the message as they’ve sent messages their entire life: in plain text.

- Sign, but don’t encrypt. If the contents of the email are public (non-confidential), but the recipient wants assurance that the suspected sender (and not an impostor) actually sent the message, then the user should sign but not encrypt. Simply follow the tutorial above, skipping over the encryption and decryption steps.

- Sign and encrypt. If the contents of the email are confidential, sign and encrypt. It does not matter whether the recipient wants assurance that the user sent the message; always sign when encrypting.

For a majority of emails that the user may send, encryption is just not always necessary. The remainder of the time, the user should sign and encrypt.

Whenever there is confidential information — such as sensitive reporting information, source address and name information, credit card numbers, bank numbers, social security numbers, corporate strategies or intellectual property — users should sign and encrypt. In terms of confidential information, users should err on the side of caution and sign and encrypt gratuitously rather than doing nothing and leaking sensitive information. As for the third option, users can sign, but do not encrypt.

Best Practices in Information Security

Despite best practices regarding the operational usage of PGP encryption, a disregard for the fundamentals of information security can still put a journalist’s communications in peril. It doesn’t matter how strong the encryption is if the user’s laptop has already been compromised, and is only a matter of time before the journalists’ encrypted communication method is in jeopardy.

Below is a short list of some high-level information security best practices. For more information on this subject, see Medill’s National Security Zone Digital Security Basics for Journalists.

Journalists should not only create strong passwords, but also avoid using the same password for anything else. Consider using a password manager.

- Keep software up to date.

Update software frequently. This helps thwart a majority of attacks to your system.

- End-Point Security Software

Make use of antivirus and anti-malware software.

- Be wary of odd emails and accompanying attachments.

When in doubt, don’t click. The goal of most phishing attacks is to either get you to download a file or send you to a malicious website to steal your username and password. If it doesn’t seem right or doesn’t make sense, try reaching out to the person via an alternate communication method before clicking.

- Stay away from pirated software.

Nothing is truly free, as these software packages can often come with unintended consequences and malicious code packaged with them.

GPG Alternatives

- CounterMail: a secure online email service utilizing PGP without the complexity of complicated key management.

- DIME – Dark Internet Mail Environment: a new approach and potential game-changer to secure and private email communications.

Additional Resources

Glossary of Terms

| Keyword |

Definition |

| Ciphertext |

Ciphertext is encrypted text. Plaintext is what you have before encryption, and ciphertext is the encrypted result. The term cipher is sometimes used as a synonym for ciphertext, but it more properly means the method of encryption rather than the result. |

| Data-at-Rest |

Data at rest is a term that is sometimes used to refer to all data in computer storage while excluding data that is traversing a network or temporarily residing in computer memory to be read or updated. |

| Data-In-Transit |

Data in Transit is defined as data no longer at a restful state in storage and in motion. |

| Digital Signature |

A digital signature is a mathematical technique used to validate the authenticity and integrity of a message, software, or digital document. |

| Encryption |

Encryption is the conversion of electronic data into another form, called ciphertext, which cannot be easily understood by anyone except authorized parties. |

| Fingerprint |

In public-key cryptography, a public key fingerprint is a short sequence of bytes used to authenticate or look up a longer public key. Fingerprints are created by applying a cryptographic hash function to a public key. |

| Key |

In cryptography, a key is a variable value that is applied using an algorithm to a string or block of unencrypted text to produce encrypted text, or to decrypt encrypted text. |

| Password Manager |

A password manager is a software application that helps a user store and organize passwords. Password managers usually store passwords encrypted, requiring the user to create a master password; a single, ideally very strong password which grants the user access to their entire password database. |

| Private Key |

In cryptography, a private or secret key is an encryption/decryption key known only to the party or parties that exchange secret messages. In traditional secret key cryptography, a key would be shared by the communicators so that each could encrypt and decrypt messages. The risk in this system is that if either party loses the key or it is stolen, the system is broken. A more recent alternative is to use a combination of public and private keys. In this system, a public key is used together with a private key. |

| Public Key |

In cryptography, a public key is a value provided by some designated authority as an encryption key that, combined with a private key derived from the public key, can be used to effectively encrypt messages and digital signatures. |

Term Definitions provided by TechTarget.com, Webopedia.com, and Wikipedia.org