After seeing confirmation that James Foley has been murdered at the hands of the barbaric terrorist group Islamic State, I have been struggling to find the right words to say – besides the obvious, which is to tell my students and fellow journalists that no story is worth giving one’s life for.

But saying that – or saying only that – would be a disservice to all of the committed and courageous journalists who have given their lives in pursuit of reporting from the most dangerous corners of the earth.

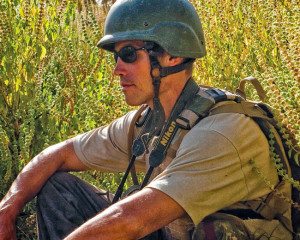

That is especially the case with Foley, a Medill grad who was kidnapped in 2012 while reporting from Syria. My former Medill colleague Steve Duke said it best on a Facebook post when he described James, his former student. “He was a brave, committed journalist who went into dangerous places so the rest of us could know what was going on,” Duke wrote.

A year before being captured in Syria, Foley was kidnapped in Libya. After his release, he wasted little time in getting back out on the front lines in search of the story – and the truth – even after acknowledging to an editor that some would think he was “crazy” for doing so.

I don’t think he was crazy at all. I think he was incredibly courageous, and the very embodiment of what it means to be a war correspondent. He was someone who risked his life to bear witness to the truth.

As such, I hope that Medill, and possibly other journalism and educational organizations will honor his life, and his death, with some form of commemoration. My humble vote: changing the name of the Medill Medal for Courage in Journalism Award to the Medill James Foley Medal for Courage in Journalism Award. The award is given to the individual or team of journalists, working for a U.S.-based media outlet, who best displayed moral, ethical or physical courage in the pursuit of a story or series of stories.

That is small consolation to his family, of course. But it would be an important symbolic statement that the Medill community values the kind of reporting that Foley and others like him have done.

Just this year, more than 30 reporters have been killed for being journalists, with many others killed or injured in the line of duty, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. Many thousands of other journalists face similar risks in conflict zones around the world every day.

The best person to speak for Foley and his commitment to journalism is Foley himself. Fortunately for us, he took the time to address the circumstances of his first kidnapping, and the lessons he learned from it, in a very frank talk at Medill in 2011. Read about it here.

Foley, a 2008 Medill grad, was emotional that day as he recounted his 44-day ordeal in prison cells in Libya to a packed audience in Evanston as part of the Gertrude and G.D. Crain Jr. lecture series.

Especially remarkable was that Foley agreed to publicly discuss his experience just two weeks after his release. He was contemplative and brutally honest about his time reporting from Libya for Boston-based GlobalPost about clashes between rebel groups and Libyan armed forces battling for control of key cities.

Previously a teacher, Foley switched to journalism in part because his brother was in the Air Force. He said he was also a frustrated writer who wanted to see the world. He said he wanted to tell the American public the real stories about war and where American taxpayer dollars were being spent in the name of protecting them.

At Medill, he took classes on national security reporting and even attended the same weekend “Hostile Environment” training seminar that I take my Washington-based students to, so they can begin the process of learning how to minimize the dangers of reporting from the field.

Foley liked embedding with U.S. troops, but that wasn’t enough. He decided that to get the real story, he had to cover the Libyan revolution by mingling with rebel groups as they advanced on government forces 500 miles southeast of Tripoli.

While doing so, Foley and three other journalists were shot at by Libyan troops in the frontline town of Brega. While three of them were taken captive, the fourth — South African photographer Anton Hammerl — is believed to have been killed in the gunfire.

“Our story is a very cautionary tale,” Foley, then 37, conceded. “We made a lot of mistakes.”

Foley told the audience that day that his Medill training, as well as his field experience, taught him that the critical aspect of covering conflicts is to be mentally strong. That came in handy, not only during his time in prisons and after media organizations and humanitarian groups successfully pressured Libyan authorities to release him and the other two journalists.

Despite his time spent in Libyan prisons, Foley said he wouldn’t stop reporting on conflicts.

“I told my editor I know this is crazy but I want to go back to Libya,” he said. “But emotionally I am nowhere near ready.”

“Feeling like you’ve survived something—it’s a strange sort of force that you are drawn back to,” Foley was quoted as saying about his Libya experience in news reports today.

Foley was back on the front lines soon enough, covering the conflict in Syria, where he wanted “to expose untold stories,” the BBC reports. The circumstances of how he was taken into custody, and by whom, are still cloudy – at least publicly. His family has asked for privacy during this impossibly difficult time.

Conclusive evidence that Foley had in fact been murdered by ISIL was still being pursued Wednesday. But his mother, Diane Foley, posted a statement on the “Free James Foley” Facebook page in which she implored the kidnappers to spare the lives of the remaining hostages, including at least one American journalist.

On a more personal note, she added, “We have never been prouder of our son Jim. He gave his life trying to expose the world to the suffering of the Syrian people.”

During his talk at Medill, Foley said his Libya experience taught him another important lesson, one that is especially relevant today with the news of his death. He said the loss of a fellow journalist had made the recovery process a lot more difficult for him.

“Every day I have to deal with the fact that Anton is not going to see his three kids anymore,” he said of the South African photographer. He told the hushed crowd that day that he believed conflict zones can, indeed, be covered safely.

“This can be done,” he said, “but you have to be very careful.” “It’s not worth losing your life,” he added. “Not worth seeing your mother, father, brother or sister bawling.”