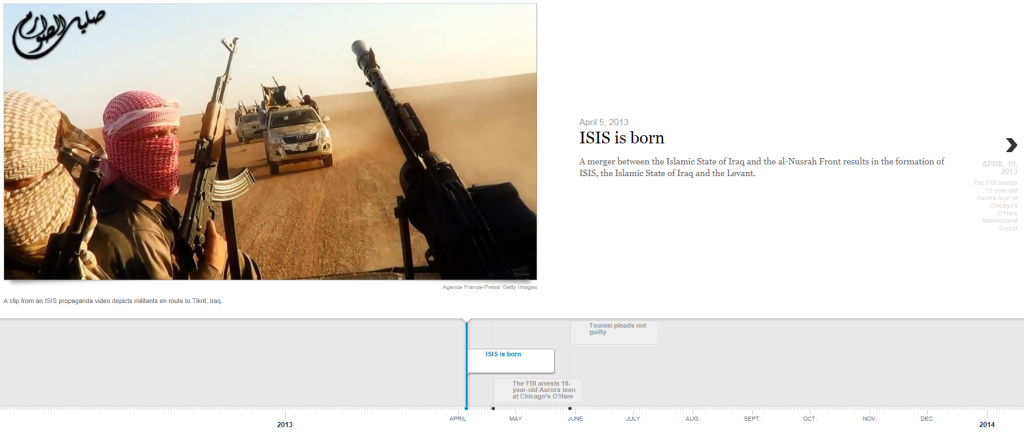

Click the image above to explore a brief timeline detailing the arrests of two radicalized Chicago teens, ISIS activity and U.S. airstrikes.

Teenage trips abroad are commonplace, meant to increase exposure to other cultures and widen points of view. But the newest iteration of that right of passage involves American teens leaving home to join terrorist causes abroad. Headlines reflect a shared theme: Law enforcement officers intercept American teen en route to the Middle East.

Some experts have identified a phenomenon where young American-born Muslims are drawn to radical Islam through social media and digital propaganda and then recruited by tech-savvy fundamentalist groups. But is this truly a trend, or are fear and headlines skewing perceptions of its prevalence?

As evidence that the threat is real, federal law enforcement arrested Bolingbrook teen Mohammed Hamzah Khan, 19, at O’Hare International Airport Oct. 4. Khan had intended to fly to Turkey and then work his way across the Syrian border to join ISIS forces.

He wasn’t the first Chicagoland teen to allegedly buy into extremist ideology. In April 2013, the FBI intercepted Aurora resident Abdella Ahmad Tounisi, then 18, as he attempted to board a flight to Turkey from O’Hare. FBI agents discovered Tounisi’s plan through the aid of a fake extremist website.

The truth is that more than 130 Americans have left the U.S. to enlist with foreign fighters in Syria in the past year alone. The majority have joined up with the Islamic State as Khan had intended to do.

“I think that there are some people who have said that ISIS isn’t an American concern, and [Khan’s arrest] shows that isn’t the case,” said Paul Rosenzweig, former deputy assistant secretary for policy in the Department of Homeland Security. “The truth is, we don’t know what we don’t know in terms of the prevalence. Khan could be one of 50 [inside Chicago]—I have no idea. And anyone who tells you otherwise, well, they don’t really know either.”

Imam Senad Agic, head of the newly established American Islamic Center in Chicago, said that immigrants’ children are most at-risk for radicalization. First-generation Muslim youth do not relate to their parents’ traditions, Agic said, which leaves them trying to contextualize Islam in a country whose culture is extremely different: “The propaganda of Islamist groups preaches a transnational society, which can eliminate the cultural anxiety felt by many of these kids.”

Local Muslim organizations have recognized the power of their influence in this arena and are now targeting outreach efforts toward Muslim teens and their parents. In a November interview with NBC Chicago, Mohammed Kaiseruddin of the Council of Islamic Organizations of Greater Chicago said that local Islamic leaders are actively working to combat forces of radicalization.

“We are basically doing a multidimensional seminar and inviting an attorney to advise of the legal problems, legal rights and so on, inviting an Islamic scholar to throw some light on the Islamic teachings in regard to this, inviting a psychologist to explain the thinking of young people, adolescent people, as to what symptoms parents should look for, and also inviting a social media expert to tell them how smartly they can use it and how not to get into trouble through the use of social media,” Kaiseruddin said.

Core to their message is that ISIS’ ideology isn’t “true” Islam.

Although the number of teens motivated to join extremist groups is relatively small, it’s important to have effective response mechanisms in place, Rosenzweig said. “Would-be Islamic radicals inside the United States aren’t going to listen to government entities, but they will listen to voices from within their own community. We must help and enable those who are part of America’s pluralistic society to talk about why violence isn’t part of the Islamic faith, and why America’s pluralism is consistent with Islam,” Rosenzweig added.

Ahmed Rehab, executive director of Chicago’s chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, told NBC that ISIS has virtually no support in his community. “We as CAIR-Chicago have been invited to various mosques, schools and centers to have a discussion with the youth, particularly with their parents, teachers and principals, about the larger story about ISIS, about youth, about the internet.” Rehab said that local imams accompany him to every panel in order to provide a valuable theological argument against ISIS.

“The majority of Muslims in Chicago are sound and healthy,” Imam Agic said. Agic served the Muslim community in Chicago’s northern suburbs for 20 years prior to his new appointment.

In September, U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder announced the launch of a new joint initiative with the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security and the National Counterterrorism Center to combat Muslim youth radicalization. Three pilot programs in Boston, Los Angeles and Minneapolis are currently underway, utilizing prevention and intervention efforts to make Muslim youth less susceptible to jihadist recruitment. The agencies have yet to release details about their specific operations or relative successes.

All three pilot cities share two things: large immigrant populations and sizeable Muslim communities. Chicago is not on the list, despite its 600,000 immigrants and global status, and there are no stated plans to expand the pilot, officials said.

Special Agent-In-Charge Robert Holley of the FBI’s Chicago Bureau put the city at a heightened threat level this past September, after telling local media that members of active terrorist groups—including ISIS—are already at work in Chicago. Holley’s announcement came a mere two weeks before Khan’s arrest, proving a prescient point: although few Muslims are jihadists, the concern is real.

“The idea that Chicago can protect itself from this is nonsense,” Rosenzweig said. “We cannot eliminate the risk, we can only reduce it.”