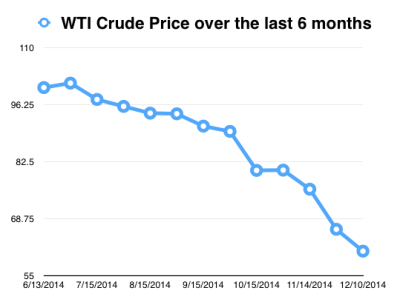

With the price of West Texas Intermediate crude oil falling to its lowest price in more than five years, and the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries aggressively maintaining its current production levels, American consumers have oil companies over a barrel.

West Texas Intermediate crude oil stands at $61.15 per barrel, a 40 percent drop from the 2014 high of $102.04 set in June.

The price rout has major oil and gas companies scrambling to delay projects and cut expenditures. This year, Chevron Corporation sold off several subsidiaries and reduced its stake in the North American shale, while Exxon Mobil Corp. cut its capital expenditures budget by 6.4 percent from 2013. ConocoPhillips announced a plan Monday to slash its 2015 capital budget by 20 percent, or $3 billion.

The question is why. Is this new energy landscape the product of temporary forces exclusive to the industry, or is it indicative of deeper economic trends?

“The supply-side narrative is important,” said Barry Bosworth, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institute in Washington, D.C., referring to the decade-long global increase in oil and natural gas production that has turned the U.S. into world’s most prolific producer of energy. “But current prices are as much a reflection of a weakened world economy as they are of having a lot of North American oil on the market.”

“What we’re really seeing here are systemic issues on the demand-side,” he added.

These include a U.S. domestic product that has yet to resume pre-2008 growth levels; a frail European economy distressed by the threat of further debt crises; the prospect of a slowdown in China and diminished Chinese demand for U.S. commodities; and technical recessions in Japan, Russia and Brazil.

“Oil is cheaper than it was, but we’re not exactly in unfamiliar territory,” said Eugene Gholz, associate professor of public affairs at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs and an adjunct scholar at the Cato Institute. Oil prices hit comparable lows in the mid-1970s, 1980s and 2000s. “The politics here are subordinate to the economics.”

The political dimension to the price drop, however, is bolstered by a clear and compelling rationale: OPEC, led by core members Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the Emirates, is averse to the U.S.’s successful intrusion into the industry that they have historically dominated. It’s retaliating by refusing to cut its production, which is driving the price of oil down, much to the consternation of American oil companies, and even to the detriment of some of the cartel’s weaker members, like Venezuela, Nigeria and Indonesia, who need all the oil revenues they can get. The result is a geopolitical staring contest, with both sides hoping the other’s losses will make them balk first.

The problem with this picture, however, which many economists are pointing out, is that OPEC may be just as flummoxed by the current production glut as everyone else.

“They weren’t banking on a million barrels of oil a day coming out of Libya,” said Charles Ebinger, a senior fellow in the Energy Security Initiative at the Brookings Institute. “The problem is that there’s nowhere for this product to move.”

Economists agree that increased demand for energy will require more than the tentative gains evinced over the last few years by the U.S. and European economies.

“Nobody is expecting a full recovery anymore,” said Barry Bosworth. “We need to adjust expectations for the advanced economies.”

European consumption has been held in check by high unemployment and debt crises in Greece and Spain, with the German-led European Central Bank having to impose painful austerity measures on the southern part of the continent.

The domestic Chinese economy, which remains underdeveloped compared with the country’s export base in the U.S., South America and elsewhere, is another trouble spot for analysts and economists, who have long advised China to look inward to achieve sustained growth.

“We’re always looking for it to taper,” said Adolpho Laurenti, chief international economist at Chicago-based Mesirow Financial, of China’s gross domestic product, which has increased at a rate of about 7 percent for the past two years. “The only question is when.”

Still, many energy sector analysts are reluctant to look too far beyond their own industry for explanations about the low cost of oil.

“Since developing fracking and all these new technologies, we knew we were entering a new era,” said Phil Flynn, an analyst at Price Group. “It’s changing the globe. But that doesn’t change the fact that OPEC just doesn’t want to give up its market share.”

“They should trust in market forces and allow for a correction, but they’re not interested in that,” he said. “They’re interested in scaring Exxon and Chevron, and it’s working.”

Whether the price drop is related more to a drop in demand or to a jump in supply, economists and policy analysts agree that it will likely have geopolitical consequences. With Libya and Algeria facing stability and security issues and Iran looking for leverage in its nuclear talks with the West, the likelihood of political realignment within OPEC is increasing.

“This situation is bringing Venezuela, in particular, closer to a domestic reckoning,” said the Cato Institute’s Gholz. “Their social experimentations do not come cheap. They would like nothing more than for oil to be $120 a barrel.”

Iran, which Gholz says “typically behaves like a price hawk within OPEC,” is another country that may be looking to make a deal to offset losses from low oil prices. U.N. sanctions against Iran, which are spearheaded by the U.S. and already gouge the country’s oil revenues, would likely be reduced were the country to come to an agreement about its uranium enrichment program.

“The situation illustrates the power of falling demand,” said Brookings Institute’s Ebinger, who also acknowledged the effect that hedge funds, many of which have dumped their positions in crude over the last year, may be playing on the price of oil, as well. “China, India, Brazil, the Eurozone — this is where things should be speeding up. We’re just not seeing what we would like to.”