WASHINGTON—When Edward Snowden leaked more than a million classified documents to which he had access while working as a credentialed contractor for the National Security Agency, Americans were shocked. Debate ensued: Was Snowden a traitor or a patriot? Were the NSA’s surreptitious surveillance programs sufficient cause for Snowden to not only break his contractual agreements with his employers, but also break the law?

Before you can answer either of those questions, two key determinations must first be made: whether Americans have a reasonable expectation of privacy in terms of their phone records, and whether the government has the reasonable right to disregard those expectations of privacy for the sake of national security. Unfortunately, popular agreement on either front has been hard to find—although the courts have spoken.

The NSA holds that its bulk collection efforts are legally protected under Section 215 of the U.S. Patriot Act, passed in response to the 9/11 attacks. Section 215 states that the government can retrieve any “tangible thing” from private persons or institutions for the purpose of protecting national security.

But what exactly was the NSA collecting? Although the surveillance programs remain technically classified, a fair amount of information has come to light over the last decade. From what we know, the government began collaborating with American telecommunication providers in the early 2000’s to share the call-detail records of their customers, a set of information that includes customer names and addresses as well as the names and numbers of the people they called.

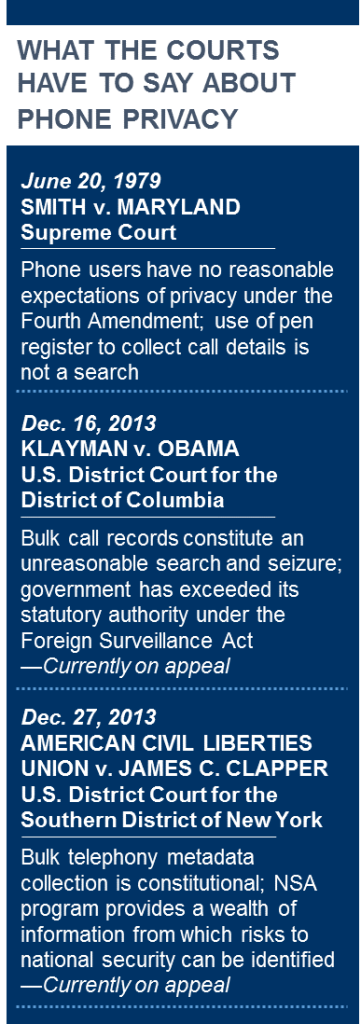

If these records are already being kept, they are certainly not secret. But more importantly, they are not private. In Smith v. Maryland, the Supreme Court ruled that telephone users have no legitimate expectations of privacy. The judgment stated that a pen register, which records call details but not the content of the call itself, did not constitute a search within the boundaries of the Fourth Amendment because the “petitioner voluntarily conveyed numerical information to the telephone company” when he chose to make a call.

The NSA’s bulk collection records collect the same information as a pen register, albeit in mass, so the constitutionality of the program’s collection seems a logical extension to some; but the courts have said that searches need to involve a specific person, not a category of people although there is some dispute about other rulings that appear to allow bulk collection for national security purposes. This would also mean that Americans do not have a reasonable expectation of privacy with regard to their call-detail records.

Following Snowden’s initial leaks in the summer of 2013, NSA Director Keith Alexander defended his agency’s bulk phone record collection programs repeatedly, touting them as a successful anti-terror tool: “They have protected the U.S. and our allies from terrorist threats across the globe.” Alexander attributed the prevention of at least 50 potential terrorist events in the years since 9/11 to NSA surveillance programs.

But he never offered a specific thwarted attack as proof of the program’s success, a point not lost on Judge Richard Leon of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. On Dec. 16, 2013, Leon challenged the overall constitutionality of the NSA’s program in Klayman v. Obama, ruling that the agency’s mass collection of metadata constituted an unreasonable search and seizure. Leon criticized the government for failing to “cite a single case in which analysis of the NSA’s bulk metadata collection actually stopped an imminent terrorist attack.”

But two weeks later, U.S. District Judge William Pauley in New York ruled the reverse, upholding the NSA’s surveillance operations as constitutional in ACLU v. Clapper. Pauley defended the NSA’s data collection scheme as a practical tool for combatting terrorism, explaining the importance of using non-conventional intelligence gathering methods in a post-9/11 world. National security takes precedence over any perceived right to phone privacy, he said.

So which is it? Does the government have the right to view our phone data if it helps keep this country safe? Or has it abused its legal authority? Both District Court rulings are currently on appeal before federal Appeals Courts, although decisions are expected sometime in 2015. It is assumed that one of these cases will then be brought before the Supreme Court and enable a binding decision on the matter of NSA surveillance. Until that time, it will depend who you ask.