WASHINGTON – In 2013, I interviewed a woman in her early twenties who asked to be identified only as Sarah for security concerns. Sarah is a childhood friend.

She is a former member of the Muslim Brotherhood, the secretive Islamist group through which Egypt’s first freely elected president, Mohamed Morsi rose to power. Morsi was removed by a military coup just a year after taking power in 2013 and his group, the Muslim Brotherhood, was banned on Dec. 25, 2014, and labeled a terrorist organization by the military-led government.

“I am not really interested in marches anymore,” Sarah said. “We are depending on the other work more,” referring to torching police cars and threatening police forces.

After months of seeing many family and friends killed, beaten and imprisoned by the security forces, Sarah had decided peaceful protest was not sufficient.

Sarah was a believer in peaceful means of protesting and calling for change, even though oppression is not new to her family. Her father is a prominent Muslim Brotherhood member, as is her mother. Her father was detained a number of times under former President Hosni Mubarak’s rule. But she never had those radical thoughts back then.

What she was exposed to throughout the past few years since the uprising has taken her to a different level. She went from so much hope for change and a better life to this – embracing violence as a means of change because she believes it’s the only viable option.

Sarah is not alone. There are thousands of young men and women in Egypt who have similar stories.

As the government intensifies the crackdown on dissent, radicalism among youths in Egypt spreads. This comes at time when militants are carrying out more sophisticated attacks in Egypt.

Egypt is creating a new generation of terrorists, a bomb that’s going to explode in the face of not only Egypt, but also the whole region.

I talked to Sarah a few months ago and wasn’t surprised by what I heard. In a phone interview, she said that many of her close friends are longing to join ISIS, they are just waiting for the right moment. They are desperate, and they have no hope, faith or trust in the system, she said.

Thousands of the Muslim Brotherhood members and their supporters staged two huge sit-ins (Rabaa and El Nahda) in Cairo and Giza to protest the removal of Morsi. http://bit.ly/1HTzbzO

Supporters of ousted Egyptian President Mohammed Morsi push to get a free meal in the tent city near the mosque in Rabaa, in Cairo, Egypt. During the holy month of Ramadan Muslims refrain from food and drink from sunrise to sunset. (Amina Ismail/MCT)

Sarah’s husband is a journalist who was arrested while covering the Rabaa massacre, one of the sit-ins the Egyptian military stormed in August 2013, killing hundreds.

He was beaten and put in solitary confinement for months during a year of imprisonment, with no formal charges brought against him. Sarah’s sister, who is a Brotherhood member, was arrested, beaten by security forces and forced to sleep on the floor in overcrowded and filthy prison cells for participating in a protest.

Sarah also was among the protestors in Rabaa. As much as she disagreed with Morsi’s performance during his one year in power, she believed that the only way he should be removed from power is through elections.

I bumped into her at the makeshift morgue in Rabaa, when I was covering the dispersal of Rabaa on August 14, 2013 for McClatchy News Service.

She was sobbing in front of a room that was packed bodies of protesters, killed by security forces.

Bodies lie in a makeshift morgue in the basement of Rabaa field Hospital, near the sire of one of the two sit-ins on behalf of ousted Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi, Wed, August 14, 2013. This is where I bumped into Sarah. (Amina Ismail/MCT) http://gtty.im/1UTdoBy

Some of her friends were among those who were covered in blood and lying on the ground in this room.

Former Defense Minister Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi took power in June 2014 after a presidential election in which he won more than 96 percent of the vote. Human rights have been suffering since his election. Sisi “has overseen a reversal of the human rights gains that followed the 2011 uprising,” according to Human Rights Watch 2014 report.

“Egypt’s human rights crisis, the most serious in the country’s modern history, continued unabated throughout 2014.”

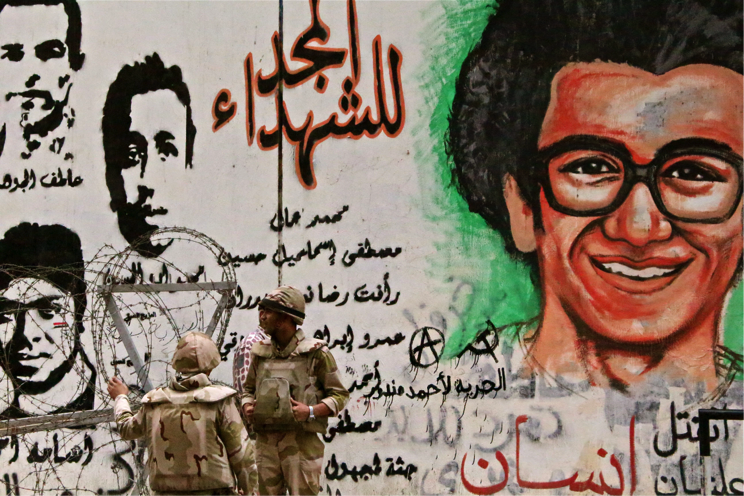

A soldier stands guard Monday, Nov. 18, 2013 near Tahrir Square in Cairo, Egypt at a memorial to those killed two years ago in clashes with security forces. Then protesters were demanding an Egypt no longer governed by the military. (Amina Ismail/MCT) MCT http://bit.ly/1IOyk4j

Nearly 2,600 people have been killed in violence in the 18 months since the military ousted Morsi in 2013, according to the National Council of Human Rights.

Hundreds of them were killed in one day — Aug 13, 2013.The carnage of that day was called “one of the world’s largest killings of demonstrators in a single day in recent history,” as described by Human Rights Watch.

Bodies of protesters killed during clashes lie on the floor of a field hospital in the Rabaa district of Cairo. Dozens also were wounded, many with gunshots to the head or chest. (Amina Ismail/MCT)

Bodies of protesters killed by Egyptian security forces lie on the floor in front of Zeynhoum Mourge is Cairo, Egypt, Saturday, Aug 15, 2013. (By Amina Ismail)

Thousands of mass arrests, abuses and torture continue to happen, though the government has never issued official numbers of arrests. According to estimates by Amnesty International, citing local human rights groups, 22,000 people have been arrested since Morsi’s ouster. Local human rights activists believe that the numbers are as high as 41,000 of people arrested, sentenced or incited.

Egypt’s jails are packed with unlawfully detained prisoners; many of them university students who were arbitrary arrested during protests or for supporting the Muslim Brotherhood. Many of the prisoners have been tortured, stripped naked, beaten and then dumped in inhumane overcrowded prison conditions, with no formal charges brought against them.

Along with mass arrests come mass trials and mass sentencing. In March 2014, 529 people were sentenced to death, in a trial that lacked basic due process protection. There was just one court session before the judge ruled on this case.

With mass trials and mass death sentences, hope for justice fades. For decades, the judiciary has been the arm of the regime.

Sisi promised to restore order and stability in Egypt.

However, since Sisi took power, terrorist attacks and violence of armed groups have dramatically escalated.

Just in the past couple of months there has been a mounting series of attacks in Egypt.

This week, the self-proclaimed Islamic State group’s branch in Sinai released a video threatening to behead a Croatian hostage if Egyptian authorities did not release all the “Muslim women” in prisons. The Croatian, who identifies himself as Tomislav Salopek, was captured on July 22 in Cairo.

The violence continues. The county’s top prosecutor was assassinated in Cairo an unknown militant group calling itself Tahrir Brigades’, militants in northern Sinai have carried an attack on soldiers killing tens of them, and the latest major attack was on the Italian Consulate’s compound in downtown Cairo, in which ISIS claimed responsibility for the bombing that resulted in the death of a man, immense damage to the building and rupture of the underground water pipes.

Sisi’s dictatorial and repressive policy is resulting in the expansion of insurgency in Egypt; Islamist youth are resorting to violence, like Sarah.

After the disposal of Morsi, hundreds of the Muslim Brotherhood leadership were arrested, leaving thousands of youth with no guidance. The leadership structure of the well-organized group was ruptured.

It isn’t just the regime that is cracking down on the Islamists, the society is also discriminating against them and the media are perpetuating this sentiment.

After the court outlawed the Muslim Brotherhood, identifying or being seen as a member of the group or even a sympathizer has became tantamount to being a terrorist. The government and media have portrayed the fight against the Muslim Brotherhood as a fight against terrorism. Media in Cairo have encouraged regular citizens to report Muslim brotherhood members to the police. TV channels have broadcasted hotlines for citizens to call upon their suspicion. The media in Egypt is controlled by the government.

A couple of weeks ago, I attended a discussion at George Washington University on the dangers and motives of foreign fighters from Europe and the U.S. who travel to the Middle East to join ISIS.

Muslims in European societies, especially in France, are not fully integrated. They are often marginalized, poor and discriminated against — motives that drive European Muslims to go to fight in the Middle East, according to Peter Neumann, director of the International Centre for the Study of Radicalization and Political Violence at King’s College London. Neumann was one of the speakers of the three-member panel.

“Imagine you are a 20-year-old Muslim in a deprived suburb of Paris and you know that you don’t have a lot of opportunities in French society,” Neumann told the audience.

“You look at the fighters’ pictures with guns, amongst brothers, who are seen as heroes in that society, who are incredibly successful and powered and admired. Yet, six months ago, looked like someone like you with no prospects in European society, with no hope and probably a life of petty crime ahead of himself.”

With social media today, it is easy to communicate with those people and create personal ties and identity, Neumann added.

Neumann’s point carries weight outside of Europe, too. Don’t Egyptians have stronger motives to join militant groups? At least, in Europe there aren’t mass arrests, torture, extreme poverty and high illiteracy rates.

The Egyptian authorities should stop relying on mass arrests, torture and death sentences to fight radicalism and shut dissent, because in fact it is contributing to the instability.

Neumann talked about the importance of integrating returning foreign fighters from the Middle East into the society — at least those who haven’t committed major crimes.

He referred to a story not widely known about the late Osama bin Laden, who was a foreign fighter in Afghanistan before he became an international terrorist. After the Soviet Union pulled out of Afghanistan and ended the war in 1980, he tried to reconcile with the Saudi government and he offered his services to help fight the first Gulf War in the early 1990s. Bin Laden didn’t have a game plan for the next 10 to 20 years. In short, he was not re-integrated into civil society.

“I think it is the same for a lot of foreign fighters who decided to return to their home countries, but they are keeping their options open,” Neumann said.

One would wonder, if the Saudi government reconciled with Bin Laden in the 90’s, would 9/11 unfold the way it did?

This is similar to the foreign fighters returning to Europe; they should be reintegrated into the society.

In Egypt, also, the government should start reconciling with the Islamist youth and reintegrate them back into the society.

Neumann had another interesting suggestion: every European country should have a hotline that parents could call – one not answered by police.

“Ninety-nine percent of parents don’t want their kids to go to Syria and die, but they often don’t call the police because as much as they don’t want their children to die, they don’t want them to go to prison for 20 years,” he said.

This suggestion could also work in Egypt, but first, the regime should start building trust with its people and put aside all the political disputes.

In 2013, Sarah warned of violent escalation if the regime continued to crackdown on dissent.

The government “is creating terrorists,” she said back then.

Unfortunately for Egypt and the world, her prediction has come true.

(Some of the quotes I’ve used in this blog are taken from a story I wrote for McClatchy Newspapers in 2013: http://bit.ly/1IOyk4j)