WASHINGTON — The idea that a traumatically injured person who receives medical attention within an hour of being injured has a higher chance of living than those who are treated later has long been taken as a military truism. It’s even got a name – the golden hour rule.

The golden hour evolved over more than a decade of conflict, but only recently has the concept been verified through a long-term study conducted by the United States Army Institute of Surgical Research, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Texas A&M Health Science Center College of Medicine and the Center for Translational Injury Research at The University of Texas Medical School at Houston. The study found that over the course of the conflict in Afghanistan, median transport time of traumatically injured patients improved from 90 to 43 minutes. The study also found that, because of this dedication to rapid transport, the fatality rate for traumatically injured troops went from 13.7 percent to 7.6 percent.

According to Brig. Gen. Kory Cornum, Air Mobility Command Surgeon of the Air Force and an orthopedic surgeon, the golden hour rules is one of a number of tools and medical practices developed during combat that have proven useful in and out of the war zone, throughout history.

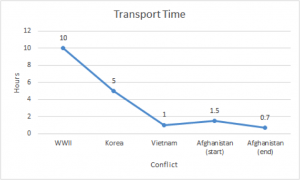

During World War II, according to an analysis done by Dr. Kendall McNabney in 1981, it took roughly 10 hours to transport an injured soldier to definitive treatment. With each war, the time decreased.

McNabney credited use of helicopters as ambulances as well as better blood programs, staffing, facilities and organizational structure as factors contributing to the survival of injured troops in Vietnam.

According to the University of Maryland Medical Center, R. Adams Cowley was the first to popularize the term “golden hour.”

During the Vietnam War, the Army sponsored Cowley to study shock trauma in patients. Through his study, the idea of the golden hour became a theme in successfully treating trauma patients.

The Medical Center quoted Cowley as saying, “There is a golden hour between life and death. If you are critically injured you have less than 60 minutes to survive. You might not die right then; it may be three days or two weeks later — but something has happened in your body that is irreparable.”

According to Cornum, tourniquets and blood therapy are two other tools that started with the military but moved to civilian medicine.

According to Cornum, massive bleeding – known as hemorrhage – kills most people with traumatic injuries. However, tourniquets – used to limit blood flow to an injured and bleeding limb, for example – were not routinely used in civilian or military trauma centers until about two decades ago.

“Twenty-five years ago, we all were taught – in Girls Scouts and Boys Scouts and in first aid training in the military and you name it — that a tourniquet was only to be used as a last resort,” Cornum said.

Tourniquets were a last resort when medical transport was less efficient because applying a tourniquet for a long period means no blood, and with it oxygen, is being delivered to tissues below the tourniqut. This eventually kills all tissue below where it is applied; in the past, amputations were the result.

“Now everybody in their combat lifesaving kit… there’s a couple of tourniquets in there,” Cornum said.