WASHINGTON — To call space debris an expensive nuisance would be a huge understatement.

With a typical impact speed of 10 km/second orbital debris, the man-made space junk that orbits the planet poses a deadly threat to human space flight and the safety of satellites.

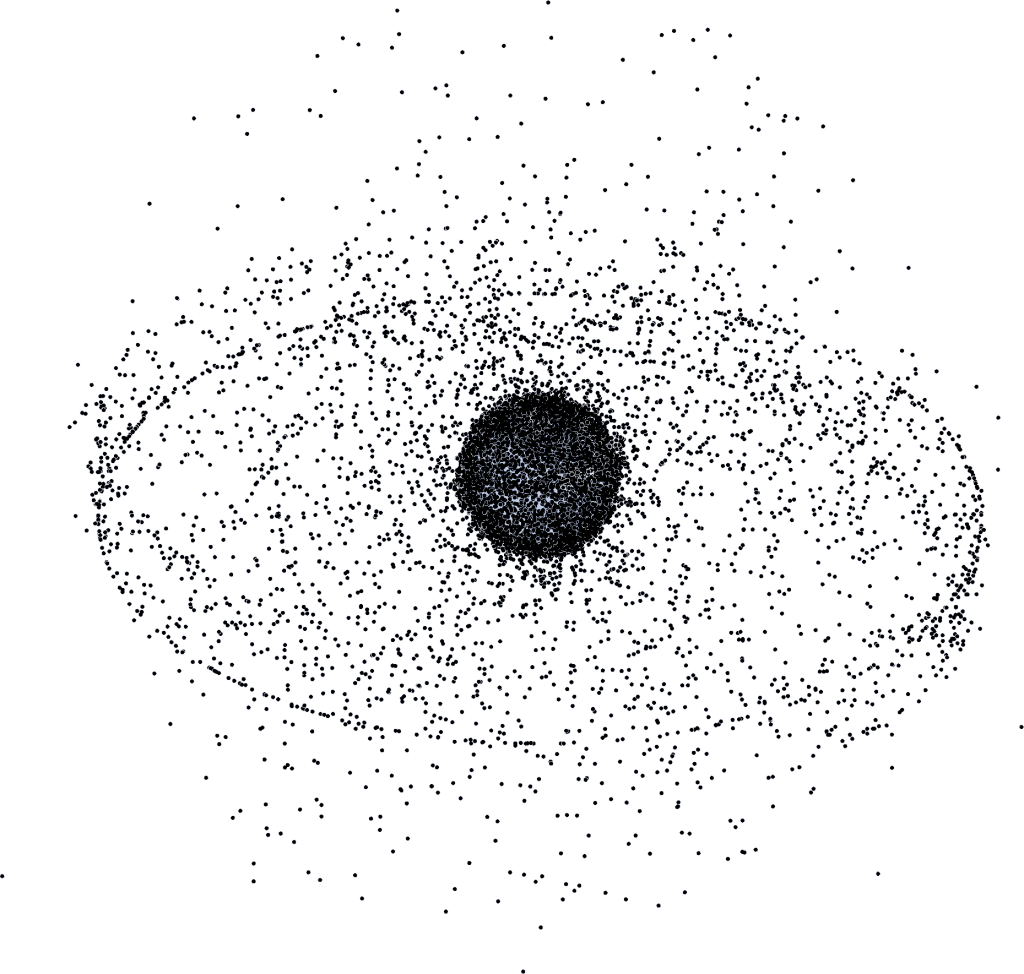

Over the decades, orbital debris has accumulated in the various levels of Earth’s orbit. The Air Force has catalogued and tracked about 23,000 objects that are four inches or larger. According to Dr. J.- C. Liou, the chief scientist at NASA’s Orbital Debris Program Office (managed by Safety Mission Assurance), the estimate for objects around 1 millimeter or larger is of the order of 100 million.

It only takes a piece as small as 0.3 millimeters to hamper space flight and even take out a multi-million dollar satellite.

The ODPO is based at NASA’s historic Johnson Space Center in Houston and monitors the orbital debris environment and develops the mitigation measures to protect the users of it.

Space’s domain differs greatly from anything in our atmosphere. Once a satellite is put into orbit, it is there indefinitely. It can’t be repaired and there are no territorial boundaries.

So the only hindrance for a nation or private firm to put up a satellite is the level of its technology to do it.

As satellites approach the end of their life span, they are either moved into higher orbit with the last of their fuel supply or left to slowly reenter the Earth’s atmosphere where they degrade enough to fall back to the earth safely.

Any remediation measures that are practical have not been implemented yet. Todd Harrison, a Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments senior fellow in defense budget studies, said that any way to try and collect the orbital debris would be highly problematic because of the sheer volume and spread of the debris and the vast size of the space in question.

Even if it were feasible, the issue of basic accountability arises because it is difficult to trace where most of the debris originated.

Protecting satellites is possible but comes at great cost because the extra mass in shielding increases the expense of launching the satellite into orbit.

“Mass is precious on satellites, so there is a huge cost to adding shielding,” Harrison said.

So national space programs and commercial satellite owners generally have two viable options to deal with the orbital debris issue: Limit the creation of more debris and stay out of the way of what’s already up there.

The ODPO’s mitigation policy seeks to carefully control the amount of orbital debris that is added to Earth’s orbit so that it grows at a manageable rate.

Low Earth orbit is the space between the altitude of 160 kilometers and 1,930 kilometers. All space stations and the majority of satellites, particularly imaging satellites, orbit in LEO. Of the roughly more than 6,000 metric tons of material whichwhich orbits the Earth, around 2,700 tons of material is in low Earth orbit.

A significant amount of this mass came from only two major collisions within the past 10 years; one intentional and one accidental.

On Jan. 11, 2007, China tested an anti-satellite missile by firing it at one of its old weather satellites. The resulting explosion produced more than 3,000 pieces of trackable debris particles and as much as 150,000 particles in total, the largest recorded creation of space debris.

Two years later, the first ever accidental collision occurred between two intact satellites in low Earth orbit. On Feb. 10, the Iridium 33 commercial satellite and the out of service Russian Kosmos 2251 military communications satellite collided at a speed of 42,120 km/hour. Both satellites were completely destroyed and over 2,000 large pieces of debris were catalogued by the U.S. Space Surveillance Network by July 2011.

These two events are responsible for doubling the amount of orbital debris in low earth orbit.

The largest threat that orbital debris poses is through what is called the Kessler syndrome. The increasing population of orbital debris increases the likelihood that they will collide and further increases the likelihood of cascading collisions after an initial impact.

The eventual worst-case outcome of this is that low Earth orbit is rendered unusable for future generations. This scenario was portrayed, albeit much more rapidly, in the 2013 popular science fiction film “Gravity.”

The U.S. government responded to this bleak outcome by creating the Orbital Debris Mitigation Standard Practices in 1997. These guidelines limit the generation of orbital debris across the U.S. NASA, the ODPO, DOD, FCC, and FAA have all developed and follow similar measures.

On May 21 Congress passed H.R 2262, the Spurring Private Aerospace Competitiveness and Entrepreneurship (SPACE) Act.

As part of the SPACE Act, Congress called for an immediate to address orbital traffic management. Among the parameters called for in the study is the review of the requirements set forth under any treaties and international agreements which the U.S. is a part of and how the Federal government complies with each.

“We are doing a reasonable job to implement the standard practices, trying to limit the generation of orbital debris,” Liou said “But of course nothing is perfect, there’s room for improvement.”

Safety Mission Assurance, which controls the Orbital Debris Program Office, has received an average of $48.1 million of NASA’s budget for safety oversight between 2011 and 2014.

“”That’s enough to think about the problem but not to actually do anything.”” Harrison said.

The estimated amount for 2015 is $48.7 million, with a request for $50.1 million in 2016. Along with the ODPO, Safety Mission Assurance also manages the Electronic Parts and Packaging Program and the Safety Center, among other operations.

NASA’s figures for Safety Mission Assurance in future years project a steady rise up to $53.2 million in 2018.

On an international scale, the standards for debris management are set by the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC), which consists of the 13 major international space agencies. The committee’s own set of orbital debris mitigation guidelines were developed in 2002 and include avoiding intentional destruction or harmful activity in space. The United Nation developed its own guidelines in 2007.

While monitoring and mitigation have gone a long way toward managing the problem, the risk of accidental collisions remains high. The consensus from a major monitoring study by the IADC expects one major accidental collision every five to 10 years for the next 20 to 30 years.

“It’s something that we expect to get worse and it’s something that we need to do a better job to control the growth of… but the sky is not really falling today,” said Liou.

Currently the biggest problem for mitigation is that the pieces that are too small to track but large enough to do significant damage.

“There’s a gap in there of stuff that is too large for shielding but too small to track and you’re just taking a risk,” Harrison said.

On June 2, 2014, it was announced that Lockheed Martin landed the $914 billion contract to build Space Fence, which would replace the Air Force Space Surveillance System as the next-generation safety net.

“When it comes online in 2018, Space Fence will enable the Air Force to locate and track hundreds of thousands of objects orbiting Earth with more precision than ever before to help reduce the potential for collisions with our critical space-based infrastructure,” said Steve Bruce, vice president for advanced systems at Lockheed Martin’s mission systems and training business.

The radar system will be based on the Pacific Island of Kwajalein Atoll. The Air Force has spent some $1.6 billion to date on the the Space Fence program, according to a March 2014 Government Accountability Office report.