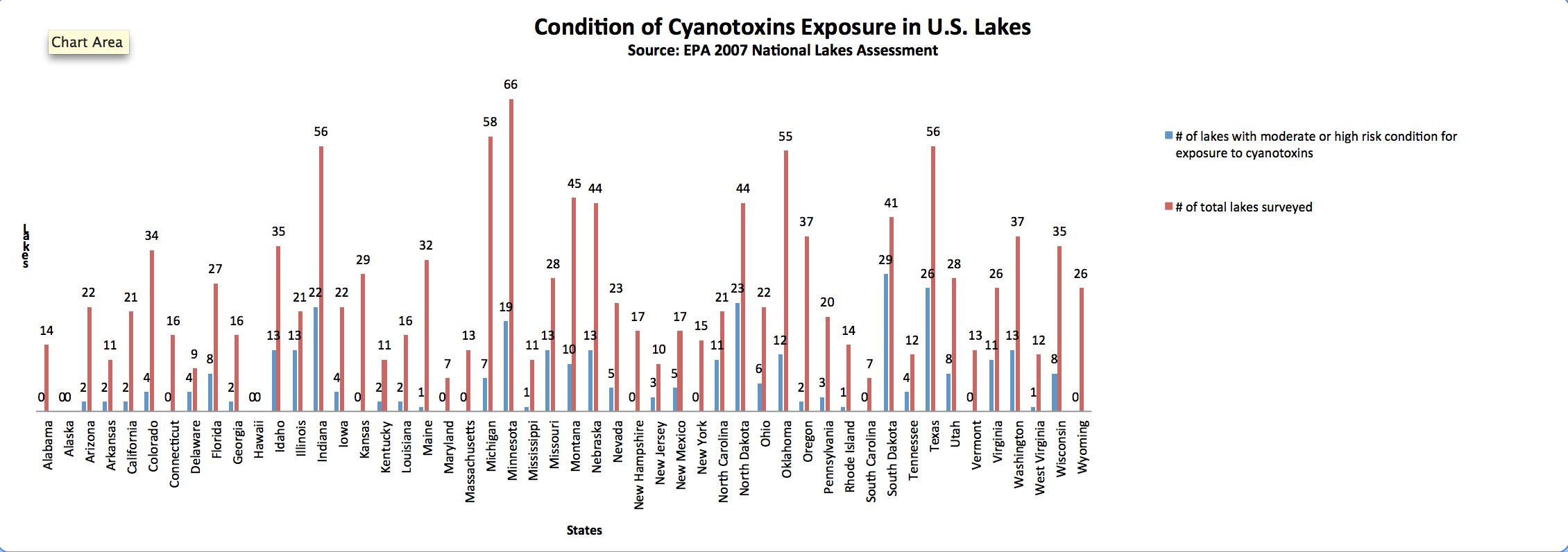

According to the World Health Organization, lakes are considered to have moderate to high health risk if the number of cyanobacteria in the water is equal to or greater than 20,000 cells/mL. The following data shows the number of lakes surveyed by EPA in 2007 and their conditions. Data source: EPA. (Yinmeng Liu/MEDILL NSJI)

BY: YINMENG LIU

WASHINGTON – It is green, slick and is usually clustered in major waterways. It has an adverse effect on human health and could be fatal to fish and dogs. Last year, it contamined the water so badly in Lake Erie that 400,000 people in Toledo, Ohio, were banned from drinking their water for two days.

Blue-green algae, the common name for cyanobacteria, thrives in warm temperatures and flourishes when excessive industrial waste is dumped into rivers. Not all algae is bad, but cyanobacteria produces microcystins, a class of toxins that can cause health problems ranging from skin rashes and body numbness to neurodegenerative diseases and tumors.

“Unfortunately, from Great Lakes to other surfaces of fresh water across the country, algal toxin produced by harmful algal blooms are producing a serious concern to human health and safety,” said Rep. Bob Latta, R-Ohio, during a February speech on the House floor.

Algae bloom is an ongoing problem not just in the U.S., but around the world. TheNational Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, says almost every U.S. state has been affected by it.

The concern for algal bloom prompted scientists at NOAA to team up with colleagues at the Environmental Protection Agency, United States Geological Survey and National Aeronautics and Space Administration to develop an early warning system. It launchedon April. 7, and is now working to detect the growth of blue-green toxins in major waterways using existing ocean color satellite images.

Blake Schaeffer, a research ecologist at EPA and the principal investigator of the task force, said the interagency effort represents the first time that satellite images are used on a global scale to monitor algae bloom.

“I never saw that being completed and I saw that that is a huge gap and really the under-utilization of a great technology tool,” Schaeffer said. “I thought this would be a great opportunity to see if that was possible.”

Richard Stumpf, who heads NOAA’s ecological forecasting effort and is the project’s head scientist at the agency, said the project was created under the auspices of the Harmful Algae Bloom and Hypoxia Control Act of 2014. The legislation created a working group of federal agencies, led by NOAA, tasked with the goal of submitting to Congress “a comprehensive research plan and action strategy to address marine and freshwater harmful algal blooms and hypoxia.”

Schaeffer said each agency contributes to the project with its expertise. Th Geological Survey, or USGS, helps with logistics on the ground; NASA and NOAA will serve as the basis of satellite intelligence because of their prior experience with the technology; EPA will interpret the satellite images and apply the findings of the project to the development of tools that help protect people and the environment.

“It brings all the partners together under one project,” said Paula Bontempi, the task force’s head scientist at NASA and the leader of the agency’s ocean biology and biogeochemistry research program. “So you’ve got research partners who are able to look at the scientific integrity of the product [that] the operational partners are using, and the operational partners were able to implement the research project for an applied setting.”

A long history of algae bloom regulations

Federal attempts to regulate the algae bloom began as early as the 1960s.

In mid- to late-1960s, large mats of algal bloom were spotted in the western basin of Lake Erie. As a result, United States and Canada signed the 1972 Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement, which called for reducing the levels of phosphorous in waterways.

The lower level of phosphorous concentration temporarily reduced the growth of algae bloom. But it reappeared in the 1990s, and large late-summer algal blooms dominated the waterways of western Lake Erie.

In 1998, concern about algae growth prompted Congress to pass the Harmful Algal Bloom and Hypoxia Research and Control Act. The legislation requested that the president established an interagency task force.

The task force authorized funding and created a national research program under the leadership of NOAA to assess and make recommendations on strategies to control algae. Congress reauthorized the program in 2004 and 2014, and allocated $20.5 million annually through 2018 for NOAA to tackle the algae problem in water bodies.

Congress also passed the Oceans and Human Health Act, creating a national research program to “improve understanding of the role of oceans in human health.” The goals of the program include providing information to prevent marine-related health problems. The program will also build on the work of the interagency task force.

Most recently, Latta, whose constituents have been heavily impacted by the algae bloom, introduced the Great Lakes and Fresh Water Algal Bloom Information Act in September 2014. The bill required NOAA to create an electronic database of researches and actions taken to control algae bloom. The bill was referred to the House Subcommittee on Fisheries, Wildlife, Oceans, and Insular Affairs on Sept. 16, 2014.

Using ocean color technologies to monitor algae

Unlike previous efforts, the current project will put eyes on algae bloom using ocean color satellite sensors, scientists involved said.

“NASA really has led this specific type of expertise initially using satellites to monitor water quality, but more so in global oceans,” said Schaeffer. “We’ve asked them to partner with us to focus more on estuaries and water bodies, such as lakes and reservoirs.”

Agencies use ocean color satellite images to detect the changes of colors in waterways caused by the presence of different materials in the water. Different materials scatter electromagnetic radiation at different wavelengths, causing a rainbow of colors.

Cyanobacteria, for example, will scatter a certain wavelength of light, which enables scientists to detect the amount and presence of the bacteria in water. The use of the ocean color technique in the project will enable the frequent monitoring of a broader area, which is more efficient than water sampling.

Bontempi said there’s a reason that the agencies are only now applying ocean color technologies to monitor algae in a global scale.

“We learn as we go along; we did better at building sensors of satellites, so we may not have the capabilities in the 70s and 80s and 90s to observe what we were able to observe in this century,” Bontempi said.

The first ocean color sensor that NASA launched is the Coastal Zone Color Scanner, which found a place on board the NIMBUS-7 satellite in 1978.

Bontempi said NASA only had two dedicated ocean color satellite platforms in the past. Besides NIMBUS-7, the other sensor is the Sea-viewing Wide Field-of-view sensor developed in 1997.

The ocean color sensors involved in this project are: Medium Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (MERIS) from European Space Agency, Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) from NASA and the Ocean Land Colour Instrument (OLCI) from ESA.

Landsat, the longest-running remote sensing technology in the world, is also employed in the project. Now in its eighth installation, the NASA-USGS coordinated satellite program has been fundamental in recording the changes of earth’s surface.

“Landsat has a 30 meters pixel, so it has the potential to give at least some information on smaller lake, few trade-offs are it’s not going to be as specific about the blooms, and also it’s relatively infrequent,” said Stumpf.

“We intend to utilize both Landsat 7 and 8 imagery where possible and will use archived Landsat imagery from previous Landsat missions to generate historical products for cyanoHABs where possible,” wrote Keith Loftin, a research chemist and the project’s lead scientist at USGS, in an email exchange.

Besides the sensors, Schaeffer said he also hopes to employ data from Sentinel 2, Sentinel 3 of the European Space Agency, and Aqua and Terra from NASA.

Recycling existing satellite images decreases financial risk

Shelby Oakley, an assistant director at the Government Accountability Office, said she sees this project as a “positive thing,” because it uses existing satellite data.

“From my perspective, if you are able to use data that you’ve already collected from satellites that you’ve already spent significant amount of money on, the more uses you can have for those data, the better,” said Oakley, “and the more effective and more returns on investment that we can get as a government.”

The base funding of the project, $3.6 million, comes from federal research dollars allocated for a competitive research program at NASA. Bontempi said NASA awarded the budget for this project based on an evaluation of its proposal.

In addition to the $3.6 million, the other three agencies will contribute to any internal costs related to the assignment, Schaffer said.

“We are also providing our personnel resources, people themselves cost money as well to do the work. That’s how each agency is contributing,” said Schaffer. “So if you really tally it up, it will be over $3.6 million.”

A major harmful algae bloom event can divest from local coastal economies tens of millions of dollars. EPA stated in a report from 2012 that the Toledo government spends up to $200,000 a month on carbon to rein in the spread of algae bloom.

A major program in NASA is defined as $250 million or more, Oakley said.

“I think if you are talking about risks, it’s certainly not going to be a financial risk that you are looking at,” she said regarding the project.

The project is awarded for five years. In addition to the satellite monitoring, scientists are also developing a mobile application and a website which will warn the public to avoid water bodies with high concentration of algae.

“To me, that’s kind of the big-picture goal with this,” Schaeffer said. “How do we really begin to deliver these water-quality satellite images in a way that people don’t have to worry so much on the technical side of things and they can use the information to make decisions going forward.”

Though the project was just launched in April, scientists have high hopes for the project’s development going forward.

“This is one of the first projects I can recall where all these federal agencies came together in such a way,” Bontempi said, “because of having all of these research and operational federal partners on board, the team has a real shot at achieving their objectives.”

“I don’t expect at the end of five years we just cut our ties and walk away, I think this will spur a lot of discussions about how do things like this become fully-operational and commonplace in the future,” said Schaeffer.